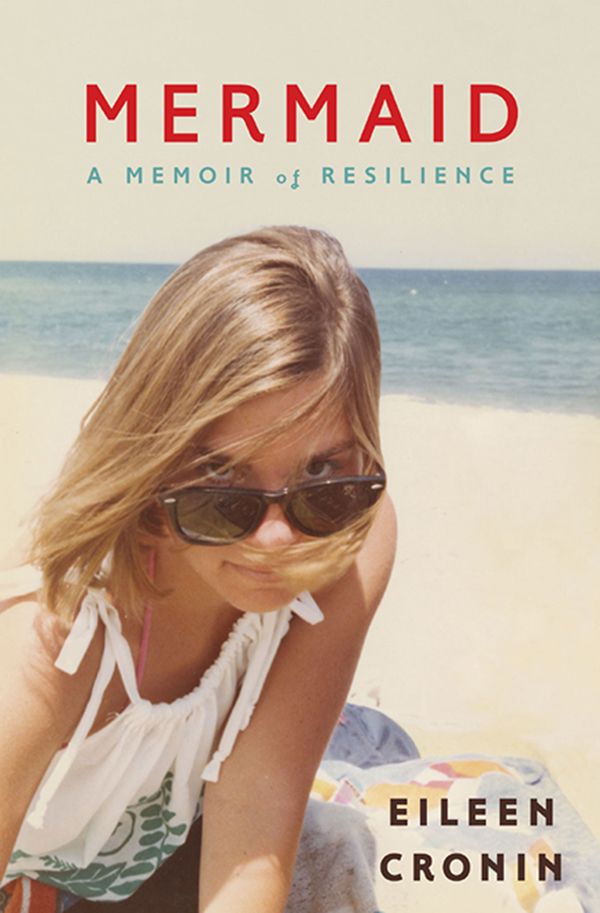

Mermaid: A Memoir of Resilience

Read Mermaid: A Memoir of Resilience Online

Authors: Eileen Cronin

For my parents, who showed me how to love and persevere,

and for Andy and Ania Sophia, who make both very easy to do.

Contents

CHAPTER

1:Tracing the Blue Light

CHAPTER

11:The Last Worst Thing That Ever Happened to Me

CHAPTER

12:How to Build an Empire

CHAPTER

15:When a Pop Diva Comes in Handy

CHAPTER

16:Venus Rises (Having Gotten a Lift from Dr. T. J. Eckleburg)

CHAPTER

20:The Gravedigger’s Granddaughter

CHAPTER

21:One Door Slams, Another Opens

CHAPTER

22:Orphans and Ophelias

CHAPTER

23:Ophelia Gets Her Feet Wet

A

long the oceanfront at dusk, my friends drag me past the fern bars and wet T-shirt contests to catch up to the aerobic pulse from the disco ahead, which we call “flashback” because its flashing lights leave you with a psychedelic impression of dancing dots when you come back onto the street. We enter when the bar is as black as the inside of a pocket. White light blinds us before a series of colors flicker.

I rush ahead to join Heidi and Jennifer, who have earned our pledge class’s reputation as the prettiest girls on campus (although I may be responsible for our “partyest girls” reputation). Because of Heidi and Jennifer, we are quickly greeted by a couple of football players from Notre Dame. Standing beside these two girls from my sorority, I could pass as their biological sister. We have tanned faces, copper-feathered hair and golden highlights—Farrah Fawcett–style—along with upturned noses and pointed chins, though typically I do not carry mine as high as the others. Back in Cincinnati, I am “that girl who was born without legs.” Yet here on spring break in Fort Lauderdale I become a beautiful girl with a limp.

The place is crowded and smells of stale beer. A sandy-blond guy with Donny Osmond teeth makes eye contact with me. I’m handed a daiquiri with a parasol and a cherry on a spear. Half of the drink is down before it freezes my brain. Over the rim of my hurricane glass I see the sandy-blond crossing the dance floor. I jam the cherry into my mouth, and when he taps my shoulder I swallow it whole. Speakers coo “How Deep Is Your Love?” I glance up and this guy is grinning at me. His lashes are longer than mine.

See, I say to myself, if not for the legs I could be another Heidi or Jennifer. I’ve been telling myself this line all year, only now I’ve got this sandy-blond guy to prove it. He is the most handsome man in the bar, this boy from where? Vanderbilt.

He wants to know about me, so I tell him I’m the highest-seeded tennis player on our varsity team—a freshman, at that.

My friends stop flirting with their fan club. Twin Farrahs turn to face me.

I’m terrified and exhilarated all at once, heart ricocheting against the walls of my chest.

This button-down boy is with me, though. He’s riding the roller-coaster grandeur of a wounded tennis star. He grabs a chair and he’s nodding his head; yes, he can see that, the bit about my athletic prowess. He squeezes my biceps. Only a tennis player could have arms like those, he says. Heidi and Jennifer bite down on a snort. I blush, and my sunburned cheeks break into a sweat. I do not explain that biceps like these come from lifting the dead weight of my entire being every time I get out of a chair. Instead I say I tripped on a tennis ball that got under my feet, don’t know how it happened, both ankles twisted, and here I am: a limping tennis star.

Heidi’s hazel eyes expand to impossible proportions. In the morning we’ll have mimosas, poolside, where we’ll laugh about taking our mothers’ schoolgirl pranks to a new level. (My mom used to spy from Heidi’s mother’s front porch on my dad, while he was being stood up on her own doorstep across the street.) I have three older sisters, and I could write a book:

The Art of Coquetry.

But honestly, because of my legs, my allegiance is with the jilted party.

Tonight, however, I take the opportunity to run with the pack of popular girls. Maybe I could break a heart?

The sandy-blond guy says he could see something like this clumsy, tennis-ball stuff happening, stuff like that happens to him all the time, but what the hell? Should we dance? Could we dance with the limp and all?

I shake my head no but he’s already standing with his hand out, the silver-studded disco ball dangling over him with its million tiny mirrors reminding me that I’m a one-in-a-million girl—and that right now I want to be one of the other 999,999. I stand up and my knee (the only one I have) begins to wobble. Colored light beams snap and scatter from the rotating ball. As soon as I accept his hand my knee steadies itself.

On our way to the dance floor he says, you sure screwed up those ankles, and I think, I’m just glad they’re attached to my feet. I don’t tell him I once stepped out of my car to find that the foot with which I’d been driving was still on the floorboard.

Mobs of couples jam onto the dance floor. My man in pink cotton takes me in his arms for this slow dance. I look up at his smile and feel a pang of concern: the lie.

And yet it is so intoxicating, this lie. I want to keep it going. I can’t believe he’s picked me. Or maybe this is how it should always be. Why not? The song ends before I’m ready to let it go and we are hurled into “Stayin’ Alive.”

I clap for my partner, mesmerized by his John Travolta hips. No man in Cincinnati moves his pelvis like that. He takes my hands in his and gives me an easy twirl. I’m light as a spirit, ready to soar.

He sees that and now he’s grinning; he has plans for us. In an instant he’s grasping my waist and lifting me up. Am I spinning? We gain momentum, and I’m reminded of my legs just as the left one comes loose. No, I scream, as he twirls me at top speed.

The left leg launches from my lemon-yellow corduroys, the penny loafer guiding the missile into the mob.

“NOW! Put me down NOW!”

He finally hears me and puts me down. I crumple to the floor, a one-legged Raggedy Ann, in the midst of a throbbing disco. My partner is still dancing, not realizing what’s happened. His face earnest, sincere, he’s reaching for the ghost-partner in front of him.

But which one of us is more naïve? He only asked for a dance. What was I expecting? Was it selfish of me to want to be beautiful just this once without disclaimers, riders, or caveats? I’m eighteen. Am I not entitled to a few delusions of grandeur? Right now I’d settle for being just another face in the crowd because here on the floor I’m about to be trampled while above me the lyrics taunt:

Ah ha ha

...

I have to get that leg. The crowd is drunk, and a wooden leg would make a nice fraternity souvenir. One last time I glance back at the sandy blond in his pink oxford shirt, still dancing. He doesn’t even notice me, the girl who now wriggles away on her elbows. And if he does, he doesn’t follow.

I

was almost four when it first occurred to me that no one else was missing legs. Flooded by questions without words to articulate them, I connected images with explanations. Those first confusing moments unravel in my mind like an old film. It begins with me being nudged awake by a waxy moon spilling silver-white light through the window as I sucked my thumb. But it wasn’t my window. I grabbed the bars to pull myself up and thought, “Where am I?”

I held my breath and searched for clues. Below was a driveway. My parents’ Volkswagens were not in it. I found instead a pearl-blue station wagon with pointed tailfins. A scary tree shook its fists at the moon, and I drew back. My bedroom was square and yellow and brand-new; this one was an attic with a gray-blue wall curling into its ceiling.

Quickly I grabbed my Gaga Bobo, stuffed a corner under my nose, shoved my thumb back into my mouth. In this aqua blanket with its frayed edges I smelled home: warm laundry, bacon frying, coffee and cigarettes.

Then I saw the black-and-white portrait of a baby crowned by a golden hula hoop: my cousin’s baby Jesus. I whipped my head to the opposite wall and saw on the nightstand a pair of cat’s-eye glasses. In the bed, I found blond hair awash in moonlight: my cousin Sally. Her hair was lighter than mine, but we shared the same bowl-shaped haircut.

I tottered backward onto the mattress. How did I get here?

Sally was a year younger than me but she had a real bed, and I still had a crib. The assignment of beds—who had a real bed and who didn’t—puzzled me.

I did not remember rolling off my parents’ bed when I was six months old and breaking my femur, the only bone in my right leg. There was something bigger than a bed troubling me, though, and I wondered if it had to do with legs. Sally had two legs and a bunch of toes, whereas mine ended at the knee, one above and one below it. I wasn’t concerned about the missing fingers on my left hand, which had been “webbed” until a surgeon reconstructed it. My sisters Rosa and Liz called it “the claw,” lovingly at times, and at other times I was not so sure.

Right now I was focused on legs, and I wondered if grown-up beds were only for people with two whole legs. When would I get some? What if they didn’t grow in? These mysteries mounted until I hurled myself against the bars of the crib and found my voice, a wrathful screech, bold and steady. My chest pressed into the foot of the crib, arms outstretched through bars, I wailed at an open door to an empty staircase.

Soon Aunt Gert climbed those stairs and scooped me up. I relaxed. “Oh, oh, oh,” she whispered, her voice soothing in that it matched my mother’s, then agitating because it wasn’t Mom’s. Gert’s arms were sturdier than my mother’s, and she sang “Goodnight, My Someone.” Every year she starred in Saint Vivian’s variety show: a bulky woman best known for roller skating in a clown suit while singing “I’m the Greatest Star” and playing a violin. Right now I wanted Mom’s meager voice and made-up lyrics to songs no one sings anymore:

Whaddaya know, Joe Joe from Kok

omo?

Before my aunt had children, she was a psychiatric nurse at the state mental hospital. Since then, she’d become every child’s mother and every adult’s best friend. I looked into her eyes and she explained that my family was on vacation. They would be back for me. Soon.

This was a soothing thought until I made the connection: my family had chosen to go on vacation without me. There were eight of us kids by then. Why was I the one they left behind?

I screamed loud and long, hoping to reach my parents wherever they had gone.

While I bellowed from my aunt’s Tudor home on a street lined with buckeye and oak trees in Cincinnati, my family was apparently trekking north to a lakeshore cottage in Michigan along with a caravan of other Catholic families. Our father owned a Volkswagen dealership. He had brought home a sleek new camper with a kitchenette, polished wooden cabinets, and foldout beds. My brother Frankie and I had built forts in it all week.

Frankie couldn’t have known they would leave without

me.