Metallica: This Monster Lives (33 page)

Read Metallica: This Monster Lives Online

Authors: Joe Berlinger,Greg Milner

Tags: #Music, #Genres & Styles, #Rock

Most of us don’t work with the people we’re married to, but many of us feel like we’re married to the people we work with. It’s a fact of modern life that

many people spend more time at their jobs than with their family That’s certainly been true for Bruce and me at times during our career. Fortunately for both of us, we have enormously supportive spouses who passionately believe in the work we do (though my wife does refer to herself as a “film widow”). Leaving Bruce to make

Blair Witch 2

was like telling him, “I think we should see other people.” I was in denial about it at the time, but it really was like a divorce. What I’m saying is that I could relate to what Metallica was going through. Getting close to people is complicated. Staying close to people for twenty years takes work. For the first time in their lives, Metallica were trying to master this emotional calculus.

In the period following James’s return, Metallica gradually began to coalesce as a band that was stronger than at any point in its history, but this was a rocky process. Lars yelling “fuck!” in James’s face was merely the most graphic and dramatic example of the tensions that existed within Metallica. There were many other moments when fault lines appeared—more than we could use. For example, during an all-band lyric-writing session we see James rolling his eyes at Lars, who is doodling cartoons on his pad in lieu of coming up with any reasonable lines. Later, we see Lars spitting water at our camera before laying down a particularly brutal double-kick-drum part on “Sweet Amber,” bristling when Bob wants him to do it again.

It was Lars who most often expressed a general feeling of frustration not directed at any one target. One day, the staff at HQ threw a fortieth birthday party for Kirk. It had a tropical theme, and everyone showed up dressed for the occasion: shorts, Hawaiian shirts, even some leis. Even “Crazy Cabbie,” a radio personality who was putting together a profile of Metallica for New York radio station K-Rock, was there and in his beachwear best.

1

For some reason, Lars never found out about the party. He arrived at HQ that day to find everyone there looking like they were ready for a day at the beach. Lars felt snubbed and stalked into another room with a plate of food to eat in silence. We followed with our camera. “Nobody throws

me

a birthday party,” he grumbled. A short time later, Phil came in to check on him and to see if he was okay Lars was in a morosely philosophical mood. “Life is an eternal birthday party for someone else,” he told a stoic Phil, and then added, “Life is a limp dick with an occasional blow job.” Phil, perhaps unsure how to respond to these witticisms, merely pointed out that Lars had made the decision to exclude himself from the fun everyone was having in the next room.

Later that day, the band did a recording session. Lars was still irritable. He

sat in the control room, seething, while Kirk, on the other side of the glass, struggled to lay down a part. Kirk became an easy target for Lars’s feelings of annoyance and jealousy about the party. “It’s like he never heard the fuckin’ song before,” he groused.

“Maybe he’s hung over,” Bob offered.

“He fuckin’ better be! Then it would be okay”

Crazy Cabbie was still hanging around. Lars turned to him and said, “You know, it’s just six chords. It’s not that hard.”

“It would be hard for me,” Cabbie said.

Lars grimaced. “Yeah, but you’re not in the guitar-playing hall of fame.”

Communicating the fractious nature of Metallica was easy compared to showing the small steps that revealed the band’s gradual coalescence in the months after the “fuck” session.

Monster is

a film about relationships, but not just the band members’ relationships with one another; it also examines Metallica’s evolving relationship with the outside world. Siblings may beat each other up, but they band together instantly the moment one of them is threatened by someone outside the family circle.

Brother’s Keeper

was as much about the Wards’ relationship to the town of Munnsville as it was about their relationship with each other. Before Delbert was arrested, most people in Munnsville were quietly contemptuous of the Wards, treating them like the village idiots. But once the police accused Delbert of murder, the town rallied to his defense. Something similar happened in Metallica-ville in the fall of 2002. At the urging of Metallica’s managers, Lars, James, and Kirk recorded some radio promos for use by the two companies that own most of the stations that have given Metallica significant airplay. As I think

Monster

makes very clear, Metallica wasn’t very happy with this decision, seeing it as a corporate sellout move. We used the scene of them goofing around and mocking the promos to demonstrate how the band was beginning to jell as a cohesive unit. The hated radio promos helped them by giving them an outside force to fight against. Once again, it was Metallica versus the world.

Moments like this one, when you could actually see the band coming together rather than falling apart, were rare. Reconciliation tends to be less dramatic than dissolution. So it was with heavy hearts that we decided we didn’t have room in

Monster

for an event that occurred four months later, when the

band united to reconnect with the world outside of the womblike safety of HQ and help James fulfill a lifelong dream at the same time. The sequence also led to yet another of the many weird synchronous experiences we had while making

Monster

, and ultimately triggered possibly the most emotional moment for Lars that we filmed but that you didn’t get to see.

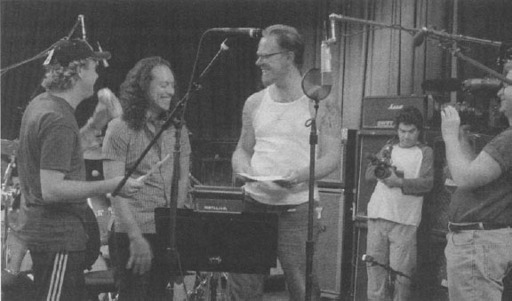

Metallica started to rally together when they collectively objected to recording a radio promo. The incident gave birth to the song “Sweet Amber.” (Courtesy of Niclas Swanlund)

Over the years, Bruce and I have developed an editing room mantra: “Sometimes you gotta slay your babies.” Our approach to editing involves constructing the great scenes first and then building a film around those scenes. Someone making a more traditional scripted documentary or writing a fictional film usually works the opposite way, first setting up a structure and then choosing the material accordingly. We prefer our method, but it does have its limitations. Sometimes, as a film’s structure begins to suggest itself during the editing process, we find that no matter how much we’ve fallen in love with certain scenes we’ve already edited, they just don’t fit into the organically evolving film. Like rabbit farmers who refrain from naming their animals so that they’ll be easier to kill, we have to discipline ourselves not to love our cinematic babies too much, because there’s always a chance we’ll have to butcher them later.

In

Brother’s Keeper

, for example, Roscoe Ward took us to some falls where

he often came as a young man “to drink beer and whiskey.” The surroundings put him in a quiet and reflective mood, and he began telling us about some of the ailments that had befallen Bill, his deceased brother. As an isolated scene, it was great, but in the interests of the overall film, we had to let it go.

2

In another doomed sequence, we filmed the Wards, who had never been more than twenty-five miles from their home, traveling to visit us in New York City. We spent a day getting great material of them absorbing the Staten Island Ferry, the World Trade Center, and Central Park. We had envisioned this material as a possible ending for the film, but in the editing room we decided that a scene that worked better was one we’d shot a day after the acquittal: the brothers trying to fix their tractor on the side of a road, and Roscoe bidding us farewell and urging us to visit again in the spring.

Some Kind of Monster

produced more babies than all our other films combined, and many, sadly, had to be put down. We instructed our editors to cull the best scenes from the material and worry about structure later. This edict caused some philosophical tension between us and David Zieff, our supervising editor, because he believed that what constitutes a “great” scene depends largely on a film’s overall structure. The problem with that approach on a film like

Monster

was that there was no obvious narrative thread. We were still shooting as he was editing, so the story could change daily. And because we were shooting so much, the babies just kept coming. We had to be ruthless killers. There was a lot of blood on our hands.

3

The baby whose death was most heartbreaking for me involved Metallica’s first performance since the return of James. On the second Sunday of 2003, James was at the Oakland Coliseum to witness the Oakland Raiders, his favorite football team since childhood, beat the New York Jets to advance to the AFC championship game against the Tennessee Titans. Talking with a friend at the game, he hit upon the idea of Metallica playing during the halftime show during next week’s game against Tennessee. On Monday, he brought it up during a band meeting at HQ. His impulsive idea took everyone by surprise.

“So, who are they playing again?” Kirk asked.

James sighed. “The Tennessee Titans.”

“Hey, be patient with me,” Kirk implored. “I don’t know shit about this stuff.”

Lars seemed similarly nonplussed, but recognized how much this meant to James. “If you want to do it, let’s do it.”

Metallica’s managers in New York were somewhat dubious. Bob would presumably play bass, but could he learn the songs in time? Would his presence

confuse Metallica’s fans and complicate the search for a permanent bass player? With Bob onstage, who would supervise the live sound mix, since the game’s halftime festivities had not been planned with a big rock show in mind? After so much time apart, would Metallica sound too rusty? Despite all these questions, the managers were relieved to see James so thrilled about playing with Metallica. “The best reason to do this,” one of them told James, “is that you want to do it.”

“For me, playing at an AFC championship is a big deal,” James said. “I was born with Raiders gear on.”

As it turned out, Jay-Z and Beyoncé were already booked for the halftime show, leaving no room for Metallica. Bob suggested that Metallica play on a flatbed truck as a treat for the tailgaters before the game. The best plan, it seemed, was for the band to just show up in the pregame parking lot, unannounced and with no fanfare, and do a quick set to show their support for the Raiders. For a band used to maintaining obsessive control over its activities, Bob’s plan was a radical idea: just show up and play.

This show would be Bob’s big day in the sun, his first live appearance with Metallica. I think management might have been concerned that a middle-aged producer like Bob Rock playing bass might somehow be detrimental to Metallica’s image (when the idea to film a pregame concert and broadcast it during halftime was still on the table, there had been talk of keeping Bob out of the frame), but it was also never clear exactly how Bob felt about being a temp in Metallica. We don’t really address this in

Monster

, but the issue was raised a few times in our presence. At Kirk’s birthday party, Crazy Cabbie wondered aloud, “Why doesn’t Bob just become the bass player?”

“That’s what I said,” the ever-affable Kirk replied.

“I’m too old and too fat,” Bob said.

Cabbie, who was sitting next to Bob behind the board, abruptly swiveled to face him, hoping to catch him off-guard. “Look me in the eyes,” Cabbie commanded. “Do you want to be in Metallica?”

Bob wasn’t fazed. “No, I’m as close to Metallica as I want to be.” (Lars found this hilarious.)

I think Bob was mostly sincere, but I suspect there was also a tiny part of him that wanted the gig. “I’m too old and too fat” was his standard response; I’d heard him say it before. But I felt there was an element of protesting too much, and probably a little bitterness. He understood intellectually that he wasn’t right for the gig—and in fact wouldn’t want to give up his life as a record producer—but on an emotional level, he wished he could be in the running. He

had been a de facto member of Metallica for almost two years. The winding down of the recording process meant the Metallica machine was revving up with various prerelease activities—thinking of a title for the album, choosing artwork, planning for the tour—which I think made Bob feel a twinge of envy toward his rock-star friends.

4

From Metallica’s standpoint, letting an outsider act like a full-fledged member was a big deal—even if it was someone as close to them as Bob, and even if it was just a daylong assignment. As far back as the Black Album, they had subjected Bob to a tiny bit of the same hostile attitude they had directed at Jason. Most of that behavior was gone by the time of the

St. Anger

sessions, but every so often you could feel the divide, especially at times when he struggled a bit in the studio while recording his bass parts for the album. Now that Bob was getting his Metallica coming-out party, he was clearly excited. During the quick rehearsals for the show that week, he exuded a boyish energy. He was obviously self-conscious and even made a joke about how the bass hid his girth better than a guitar. The band weren’t about to make it any easier for him. “Maybe you could play in the same tempo as the rest of us,” James suggested after one song, causing Bob to blush.