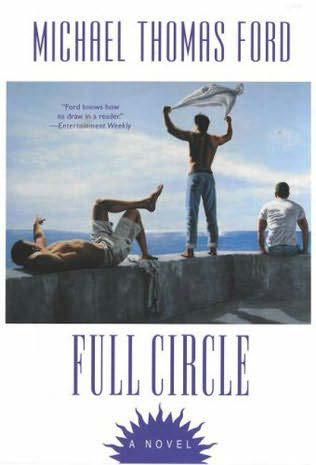

Michael Thomas Ford - Full Circle

Read Michael Thomas Ford - Full Circle Online

Authors: Michael Thomas Ford

Acknowledgments

As always, much gratitude and appreciation to Mitchell Waters and John Scognamiglio, who let me do it one more time. Also to David Berry, whose kind assistance made the writing of this novel much more interesting. And mostly to Patrick, Andy, Sam, and George, who make a house a home. Author's Note

Although this is a work of fiction, numerous people, places, and events from real life make appearances in the story. As much as possible, I have drawn on personal recollection and firsthand accounts when writing about these things. In some instances, most notably in the speech given by Harvey Milk at the 1978 Gay Freedom Day rally, I have incorporated fictional dialogue with actual transcripts from the event in order to better convey the sense of what occurred.

"Ned, it's Jack."

I open my eyes and look up into the shadows that fill the ceiling over the bed. Rain is falling, drumming on the roof, and vaguely I make a mental reminder to clean the gutters before the storm promised by the weatherman on the evening news arrives in full force. Tomorrow, perhaps, after I finish grading the stack of freshman essays sitting on my desk in the next room. If I can find the ladder in the mess that is the barn.

Beside me, Thayer rolls onto his back and breathes deeply. As usual, he's somehow managed to pull most of the quilt around himself so that he's cocooned in warmth. I both admire and resent his ability to sleep so fully, like a child. Or a dog, I think, as on his smaller bed beside ours Sam imitates Thayer, stretching his big paws and sighing contentedly.

How old is Sam now? I count back, ticking off the years. Eleven? No, I correct myself. Twelve. Twelve years since Thayer and I returned from the Banesbury County Animal Shelter with him sitting between us on the seat of our pickup, nose raised hopefully as he sniffed the air for the scent of home. Even then his paws had been enormous, hinting at the great lumbering beast he was soon to become. Twelve years. How did they slip by so quickly, turning the lively puppy we couldn't keep away from the pond behind the house into the gray-muzzled fellow who now spends most of the hours asleep in a pool of sun on the porch? What have they done, too, to Thayer and myself? Somewhere in that rush of days we've slipped from our forties into our fifties, our hair graying and our bodies beginning to betray us in small ways—eyesight that proves more and more unreliable, muscles that complain more than they used to about getting the chores done. My last birthday was number 56, and Thayer will catch up to me in less than a month's time.

We are, all of us—men and dog—growing old together. Older, Thayer says whenever I mention the unstoppable advancement of time. Not old. "We'll never be old," he says defiantly, kissing me on top of my head where my hair is thinning. "And you shouldn't worry so much," he tells me. "It's burning a hole in your head, like a crop circle."

This eternal optimism is one of the many things I love about this man, my partner for nearly fifteen years. He is the antidote to my suspicion that the world is forever on the brink of calamity, teetering perilously between salvation and destruction, ready to tumble headlong toward annihilation at the merest push. He saves me from myself on a daily basis. And he bakes the sweetest apple pie I have ever tasted. What he sees in me I don't know and am afraid to ask, in case thinking about the answer finally makes him see what a fool he's been to stick around.

And what of Jack? Has Jack aged along with the rest of us? I can't help but wonder. Although I'm trying desperately to distract myself from thinking about him, he intrudes, pushing his way in as he always has, as if he belongs in the room simply because he wants to be there. It's how he's always approached the world. I know from far too much past experience that now that he's settled in, he won't go away, so I give in and pull back the covers.

The wood floors of our old farmhouse are cool beneath my feet, and groan softly as I walk from the bedroom, down the hallway, and into my office. Sitting at my desk, I turn on the lamp and surround myself with a circle of light. Pushed back, the darkness retreats through the window. The rain seems to dilute the blackness, and through the thinning night I see the outline of the barn. Beyond it is the pond, and beyond that the blueberry bushes and, finally, the woods. This is the place I call home, the place where until Jack's phone call I believed that I was safe from the past.

"Ned, it's Jack." And just like that the ground fell away beneath my feet. Even now, hours later, I still feel as if I'm tumbling through the air, waiting to hit the ground. I open one of the desk's drawers and remove an envelope. Yellowed with time, it's addressed to a house I no longer live in, on a street thousands of miles away, in a city I left long ago without looking back. Inside is a card decorated with a Christmas scene and signed with a hastily-scrawled signature. Tucked into the card are two photographs.

I don't know why I've kept either the card or the photos. I'm not by nature a sentimental man, a trait that confounds Thayer, a hopeless romantic who still has the flowers I gave him on our first date, dried and stored in a box somewhere in the attic. I don't believe in cataloging my past, surrounding myself with reminders of people and places. What I want to remember I keep in my head. But I've held on to these, although until Jack's call I hadn't looked at them in a very long time, and had to unearth them from a box of old tax returns and unfiled articles in my closet. Now, seeing them for the first time in many years, I'm reminded of something a photographer friend once told me. "The only subjects that photograph completely naturally," she said, "are children and animals. The rest of us are afraid the camera will see us for who we really are."

In the first photograph, Jack and I are children, probably four or five years old. We're dressed in nearly identical outfits—cowboy costumes complete with hats and little pistols. Jack is waving his gun at the camera and beaming, while I look at the gun in my hand with a perplexed expression, as if concerned that at any moment it might go off.

As I look at the boys Jack and I once were, I can't recall the occasion for the cowboy getups. It's one of the many childhood moments that have disappeared from the files of my memory like scraps of recycled paper. Without the photographic evidence, I'd be unable to prove its existence at all. But there we are, the two of us, captured forever as we appeared in that one brief moment in time. The occasion of the second photograph I remember more fully. It was a birthday party for a mutual acquaintance. This time Jack and I are men nearing forty. It was one of the last times I saw him. Once again, Jack is smiling for the camera while I look away, caught in profile. Gone are the cowboy outfits, and there are no guns in our hands, but something much more dangerous separates us. A man. Andy Kowalski.

Andy stands between Jack and me. We flank him, like guards, although neither of us touches him. Andy regards the photographer with disinterest, his handsome face perfectly composed as if he is alone in front of a mirror. Once again I think of animals and children and how they lack the fear of being betrayed by the camera. Andy Kowalski is something of both.

These two photographs, taken decades apart, roughly mark the beginning and the end of my relationship with Jack. With Andy, too, although our time together was only half as long. Both friendships were laid to rest when I came to Maine to start my life over again, when I left behind everything I knew and everything I was, to become something else.

But the past has apparently decided not to stay buried. Jack's call has opened a door I thought to be long shut and locked. Now it stands open, waiting for me to walk through. When I look beyond it, though, all I see is a room filled with dusty boxes, boxes best left unopened.

"What are you doing up so early? When I woke up and you weren't there, I thought maybe my mama was right after all and the Rapture had come and Jesus had swept you into his bosom. I was afraid you'd left Sam and me to face the army of hell all on our own."

I sigh. Although he knows the basic outline of my life's story, Thayer has heard very few of the details. Not because I fear knowing them would change how he feels about me, but simply because I've never felt the need to tell them.

He leaves me alone with the photos and with the memories that are starting to push their way into my thoughts. Do I really want to tell him about Jack and Andy? Can I even remember it all and make some sense of it? I teach history to my students, but my own is one I'm not sure that I'm completely qualified to relate. I fear that given my role in the events, I'm an unreliable narrator. At best, my memories are tarnished by years spent trying to erase them, so that what remain are faded, possibly beyond recognition.

Still, I find that part of me wants to tell the story. Maybe, I think, it will help me decide what to do about what Jack has called to tell me. More likely, it will simply resurrect old ghosts. Either way, Thayer is waiting downstairs with coffee, and I find that I can no longer sit up here alone. I leave the photos behind and descend the creaky staircase to the first floor. The smell of coffee scents the air, and the kitchen is comfortingly lit. The doorway glows, and through it I see Thayer setting two mugs on the table. Sam has followed him downstairs and has stretched himself out on the floor. His tail thumps against the worn planks as I enter and sit down, and then he closes his eyes and settles back into sleep.

CHAPTER 1

For many reasons, August of 1950 was not a pleasant time to be nine months pregnant, particularly for my mother, Alice Brummel. The war in Korea, less than two months old, weighed heavily on the minds of Americans everywhere, and my mother was no exception. Worried that there might be rationing, she'd taken to buying large quantities of things like bread, sugar, and coffee, all of which she stored in the basement, along with bottles of water and extra blankets, which she fully expected to need when the North Koreans began running rampant through Pennsylvania and it became unsafe to venture outdoors unarmed.

When she wasn't stocking up on emergency supplies, she was contending with my father, Leonard Brummel. Unlike his wife, my father felt that the whole Korean business would be settled swiftly and efficiently by the superior war-waging power of the good old U.S. of A. Unconcerned for his own safety, he was therefore free to focus instead on the war raging between his beloved Philadelphia Phillies and everyone else in major league baseball.

The summer of 1950 belonged—as far as the entire baseball-loving population of Pennsylvania was concerned—to the team that had been dubbed the Whiz Kids. Young, cocky, and with the talent to back up their attitude, the Phillies had stormed to the front of the National League thanks to the work of guys like Andy Seminick, Granny Hamner, Dick Sisler, and Robin Roberts. These resident gods of Shibe Park were my father's sole interest during those hot, sticky days, and every evening he came home from his insurance salesman job, settled into his favorite chair with a bottle of Duke beer, and listened to the night's game on the radio.

My mother was not without a sympathetic ear, however. As luck would have it, her best friend and next-door neighbor, Patricia Grace, was also pregnant. Like my father, Patricia's husband, Clark, was also unavailable for support, but not because he was in love with a baseball team. Clark Grace, who didn't know an earned run average from a double play, was a scientist—a physicist—and suddenly much in demand by the military. He was currently spending most of his time in Washington, working on something he described vaguely to his wife and neighbors as "a possible new fuel source made from hydrogen."

With their husbands otherwise occupied, Alice and Patricia spent most of their time together. As their bellies swelled in tandem, they passed the mornings playing cards while lamenting their sleeplessness, their hemorrhoids, and the utter unattractiveness of maternity clothes. Out of concern for the welfare of the country, they were careful to limit themselves to two cups of coffee and four Lucky Strikes apiece, not wanting to take more than their share. In the afternoon, they did their shopping at DiCostanza's grocery store and, if Clark was staying in Washington, made dinner together in Alice's kitchen, leaving a plate in the refrigerator for Leonard before going downtown to see a movie or sit in the park. If Clark was home, dinners would be made and eaten separately, but as soon as Leonard was ensconced in front of the radio and Clark in his study, the two women would be out the screen doors of their kitchens and on their way.