Michelangelo's Notebook (2 page)

Read Michelangelo's Notebook Online

Authors: Paul Christopher

Tags: #Mystery & Detective, #General, #Psychological, #Suspense fiction, #Suspense, #Fiction

“All right.”

Sister Benedetta picked up a small bell from the mantel of the fireplace and rang it. The sound was harsh in the room. A few moments later a very young woman appeared, looking uncomfortable in a skirt, blouse and sweater. She was holding the hand of a young boy of about three. He was wearing short pants, a white shirt and a narrow tie. His dark hair had been slicked back with water. He looked very frightened.

“Here is the boy. This is Sister Filomena. She will take care of his needs. She speaks both German and Italian so there will be no problem in understanding her requirements for herself and the child.” She stepped forward, kissed the young woman on both cheeks and handed her the travel documents and the birth certificate. Sister Filomena tucked the papers in the deep pocket of her plain cardigan. She looked as terrified as the child. Bertoglio understood her fear; he’d be frightened if he were going where she was headed.

“The boat I came in has gone. How will we return to the mainland?”

“We have our own transportation,” said Sister Benedetta. “Go with Sister Filomena. She will show you.”

Bertoglio nodded, then snapped his heels together. His arm began to move stiffly upward in the Fascisti salute and then he thought better of it; he nodded sharply instead. “Thank you for your cooperation, Reverend Mother.”

“I do it only for the child; he is innocent of all this madness… unlike the rest of us. Good-bye.”

Without another word, Bertoglio turned on his heel and headed out of the room. Sister Filomena and the child followed meekly after him. In the doorway the child paused and looked silently back over his shoulder.

“Good-bye, Eugenio,” Sister Benedetta whispered, and then he was gone.

She moved across to the window and peered through the louvers, watching as the three figures moved down to the dock. Dominic, the young boy from the village who helped with the chores, was waiting by the dock. He helped the child into the convent’s dory, then helped Filomena to her seat as well. The maggiore sat in the bow like some ridiculously uniformed Washington crossing the Delaware. Dominic scrambled aboard and unshipped the oars. A few seconds later they were moving out into the narrow bay between the island and the mainland.

Sister Benedetta watched until she could no longer make out the figure of the child. Then she made her way out of the common room and down a long corridor between the individual cells, finally reaching an exit door in the lower section of the building behind the baths and toilets. She stepped outside into the failing late-afternoon sunlight and followed a narrow cinder path up the hill to the cemetery. Bypassing it, she went farther, into the dark trees, finally reaching a small dell filled with flowers and the dark scent of the surrounding pines.

She followed the path down into the saucerlike enclosure, listening to the sighing wind high above her and the distant weathering roar of the sea. If Katherine had loved anything she had loved this place; her only peace in a bruised life of fear and apprehension. The priest from Portovenere would not sanction her burial on sanctified ground, and in the end Sister Benedetta had not argued. There was no doubt in her mind that this place was closer to God than any other and that Katherine would have preferred it.

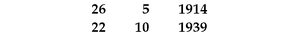

She found the simple marble cross without difficulty, even though ivy had grown up around it. She dropped to her knees, taking the time to pull the creeping tendrils away from the stone, revealing the inscription:

Slowly Sister Benedetta unwound the rosary she kept on her right wrist and clutched it in both clasped hands. She stared at the stone and whispered the old prayer of the popes that had amounted to the young woman’s last words before she threw herself into the sea:

“It is sweet music to the ear to say:

I honor you, O Mother!

It is a sweet song to repeat:

I honor you, O holy Mother!

You are my delight, dear hope, and chaste love,

my strength in all adversities.

If my spirit

that is troubled

and stricken by passions

suffers from the painful burden

of sadness and weeping,

if you see your child overwhelmed by misfortune,

O gracious Virgin Mary,

let me find rest in your motherly embrace.

But alas,

already the last day is quickly approaching.

Banish the demon to the infernal depths,

and stay closer, dear Mother,

to your aged and erring child.

With a gentle touch,

cover the wary pupils

and kindly consign to God

the soul that is returning to him.

Amen.”

The wind grew louder as it swept through the trees, answering her, and for a single moment of peace, the faith of her childhood returned and she felt the joy of God once more. Then it faded with the rolling gust and the tears flowed down her cheeks unchecked. She thought of Bertoglio, of Filomena and the child. She thought of Katherine, and she thought of the man, the arrogant unholy man who had done this to Katherine and brought her to this end. No prayer of popes for him, only a curse she’d once heard her mother speak so many years ago.

“May you rot in your tomb, may you burst with maggots as you lie dead, may your soul rot into corruption before the eyes of your family and the world. May you be damned for all dark eternity and find no grace except in the cold fires of hell.”

Her hair was the color of copper, polished and shining, hanging straight from the top of her head for the first few inches before turning into a mass of wild natural curls that flowed down around her pale shoulders, long enough to partially cover her breasts. The breasts themselves were perfectly shaped and not too large, round and smooth-skinned with only a small scattering of freckles on the upper surface of each mound, the nipples a pale translucent shade of pink usually seen only on the hidden inner surfaces of some exotic sea-shells. Her arms were long and stronger-looking than you might expect from a woman who was barely five foot six. Her hands were delicate, the fingers thin as a child’s, the nails neatly clipped and short.

Her rib cage was high and arched beneath the breasts, the stomach flat, pierced by a teardrop-shaped navel above her pubis. The hair delicately covering her there was an even brighter shade of hot copper, and in the way of most redheaded women, it grew in a naturally trimmed and finely shaped wedge that only just sheltered the soft secret flesh between her thighs.

Her back was smooth, sweeping down from the long neck that was hidden beneath the flowing hair. At the base of her spine there was a single, pale red dime-sized birthmark in the shape of a horn, resting just above the cleft of the small, muscular buttocks. Her legs were long, the calves strong, her well-shaped ankles turning down into a pair of small, high-arched and delicate feet.

The face framed by the cascading copper hair was almost as perfect as the body. The forehead was broad and clear, the cheekbones high, the mouth full without any artificial puffiness, the chin curving a little widely to give a trace of strength to the overall sense of innocence that seemed to radiate from her. Her nose was a little too long and narrow for true classical beauty, topped by a sprinkling of a dozen freckles across the bridge. The eyes were stunning: large and almost frighteningly intelligent, a deep jade green.

“All right, time’s up, ladies and gentlemen.” Dennis, the life drawing instructor at the New York Studio School, clapped his hands sharply and smiled up at the slightly raised posing dais. “Thanks, Finn, that’s it for today.” He smiled at her pleasantly and she smiled back. The dozen others in the studio put down an assortment of drawing instruments on the ledges of their easels and the room began to fill with chatter.

The young woman bent down to retrieve the old black-and-white flowered kimono she always brought to her sessions. She slipped it on, knotted the belt around her narrow waist then stepped down off the little platform and ducked behind the high Chinese screen standing at the far side of the room. Her name was Fiona Katherine Ryan, called Finn by her friends. She was twenty-four years old. She’d lived most of her life in Columbus, Ohio, but she’d been going to school and working in New York for the past year and a half, and she was loving every minute of it.

Finn started taking her clothes off the folding chair behind the screen and changed quickly, tossing the kimono into her backpack. A few minutes later, dressed in her worn Levi’s, her favorite sneakers and a neon yellow T-shirt to warn the drivers as she headed through Midtown, she waved a general good-bye to the life drawing class, who waved a general good-bye back. She picked up a check from Dennis on her way out, and then she was in the bright noon sun, unchaining the old fat-tired Schwinn Lightweight delivery bike from its lamppost.

She dumped her backpack into the big tube steel basket with its Chiquita banana box insert, then pushed the chain and the lock into one of the side pockets of the pack. She gathered her hair into a frizzy ponytail, captured it with a black nylon scrunchie, then pulled a crushed, no-name green baseball cap out of the pack and slipped it onto her head, pulling the ponytail through the opening at the back. She stepped over the bike frame, grabbed the handlebars and pulled out onto Eighth Street. She rode two blocks, then turned onto Sixth Avenue, heading north.

The Parker-Hale Museum of Art was located on Fifth Avenue between Sixty-fourth and Sixty-fifth Streets, facing the Central Park Zoo. Originally designed as a mansion for Jonas Parker—who made his money in Old Mother’s Liver Tablets and died of an unidentified respiratory problem before he could take up residence—it was converted into a museum by his business partner, William Whitehead Hale. After seeing to the livers of the nation, both men had spent a great time in Europe indulging their passion for art. The result was the Parker-Hale, heavily endowed so that both men would be remembered for their art collection rather than as the inventors of Old Mother’s. The paintings were an eclectic mix from Braque and Constable to Goya and Monet.

Run as a trust, it had a board that was gold-plated, from the mayor and the police commissioner through to the secretary to the cardinal of New York. It wasn’t the largest museum in New York but it was definitely one of the most prestigious. For Finn to get a job interning in their prints and drawings department was an unquestionable coup. It was the kind of thing that got you a slightly better curatorial job at a museum than the next person in line with their master’s in art history. It was also a help in overcoming whatever stigma there was in having your first degree from someplace like Ohio State.

Not that she’d had any choice; her mom was on the Ohio State archaeology faculty so she had attended free of charge. On the other hand she wasn’t living in New York for free and she had to do anything and everything she could to supplement her meager college fund and her scholarship, which was why she worked as an artists’ model, did hand and foot modeling for catalogs whenever the agency called, taught English as a second language to an assortment of new immigrants and even babysat faculty kids, house-sat, plant- and pet-sat to boot. Sometimes it seemed as though the hectic pace of her life was never going to settle down into anything like normalcy.

Half an hour after leaving the life drawing class she pulled up in front of the Parker-Hale, chained her bike to another lamppost and ran up the steps to the immense doorway capped by a classical relief of a modestly draped reclining nude. Just before she pulled open the brass-bound door, Finn winked up at the relief, one nude model to another. She pulled off her hat, slipped off the scrunchie and shook her hair free, stuffing hat and scrunchie into her pack. She gave a smile to old Willie the gray-haired security guard, then went running up the wide, pink marble staircase, pausing on the landing to briefly stare at the Renoir there,

Bathers in the Forest

.

She drank in the rich graceful lines and the cool blue-greens of the forest scene that gave the painting its extraordinary, almost secretive atmosphere and wondered, not for the first time, if this had been one of Renoir’s recurring fantasies or dreams: to accidentally come upon a languorous, beautiful group of women in some out-of-the-way place. It was the kind of thing you could write an entire thesis about, but no matter what she thought about it, it was simply a beautiful painting.

Finn gave the painting a full five minutes, then turned and jogged up the second flight. She went through the small Braque gallery, then went down a short corridor to an unmarked door and went inside. As in most galleries and museums, the paintings or artifacts were shown within an inset core of artificial rooms while the work of the museum actually took place behind those walls. The “hidden” area she had just entered contained the Parker-Hale’s prints and drawings department. P&D was really a single long room running along the north side of the building, the cramped curators’ offices getting the windows, the outer collections areas lit artificially with full-spectrum overheads.