Midlife Irish (27 page)

Authors: Frank Gannon

I had been in hundreds of rooms like this in America, and now, even though I was an ocean away, I was back in one. Things

started climbing the ladder of my consciousness. We had checked into the hotel because we were tired and lost. I was

still

tired. I had just completed, oh, nine hours of sleep, but I found that I wanted a few more hours. But no. I drank some coffee

and got ready for another day in Ireland. It was very odd in that hotel room. We were well rested and everything was nice,

but it seemed that we were more in America than in Ireland. I stumbled over to the shower.

I must admit that it was very comforting to experience great water pressure again. After showers, we dressed, packed our bags,

and went down to eat breakfast.

Although it was on the menu, we didn’t order the “Irish Breakfast.” It didn’t seem right to eat it in this huge room. I saw

some people at a nearby table eating it, the same massive artery-clogger. The people eating it were wearing suits. One took

a call while he was eating it. Cell phones and Irish breakfast? Blasphemy!

I listened to their voices. Yes, Irish people. But Irish people with yellow ties. The infamous Irish yuppies. I had heard

of their existence but, up until now, I had thought them to be mythological. (I would see many more of them later.)

Paulette had a fried egg and bacon. I had cornflakes. I felt as Irish as Gorbachev.

We paid our bill and went to our car. We were feeling what Frank Kermode called “the Sense of an Ending.” We knew that it

was time to begin phase two of our Irish experience. Time to look for Mom and Dad.

Mom and Dad

Mom and Dad

In 2002 most of the Irish people are in America. In 1841, the population of Ireland was 8,175,124. By 1926, the population

sank to 4,228,553. During the years between 1841 and 1926, the world’s population more than doubled. Ireland’s numbers are

a reminder of the enormous suffering the little country went through during those years. A lot of Irish people died, but a

lot more left. And it is not inaccurate to say that today a large part of the Irish population is living in America.

The Irish started arriving in America in the 1820s. Economically, things were disastrous in Ireland, but they became much

worse. The potato famine between 1845 and 1847 brought about one and a half million Irish people to America.

Most of the Irish people who left Ireland for America were, of course, poor. For the most part they stayed where their boat

landed, New York, Boston, and, a little later, Chicago. Those three cities have massive Irish populations, but there are Irish

people all over America. Montana, for instance, had a huge number of Irish immigrants.

According to the 1980 census, the Irish and their descendants form the third largest ethnic group in America. This massive

exodus from Ireland has always produced big questions: Were the people who left Ireland castoffs, the dregs of society? Or

were they actually the best of Ireland, the most ambitious: people whose aspirations could never be satisfied

in their little homeland? These are impossible questions, but I know what my dad would say. For him, people who chose to live

in a country like Ireland, when America was right here, merely three thousand miles away, were insane or lazy. For him, America

saved him from a life of misery, working on a farm and living pretty much the way his people had lived for centuries. For

a lot of Irish people, however, the rewards of the Old Country were more than enough, something they embraced and welcomed.

There is something undeniably beautiful in the rural way of life in the West of Ireland; it’s not something to be “saved”

from.

In 1990 Mary Robinson, the president of Ireland, stated that there were 70 million Irish people living outside Ireland, most

of them in the United States. So there is an Ireland that exists squarely in the United States, and it is much larger than

the real Ireland. It is composed of people whose families had lived in Ireland for centuries, but now lived in America.

The list of Americans of Irish ancestry is pretty well-known, but some names still surprise. Buffalo Bill Cody. Butch Cassidy.

William S. Hart. John Ford. Cardinal Spell-man. Bill Murray. Jimmy Cannon. James Cagey. Bugs Moran. Grace Kelly. Nelly Bly.

Jimmy Walker. Buster Keaton. John Huston. Bing Crosby. And on and on.

As the new century starts, Irish-Americans are, for the first time in history, going back to Ireland. This drastic change

in the situation of the Irish-Americans is a nearly exact reversal of what has always been the pattern. While writing this

book, I’ve met and talked to many people, some of them young and ambitious, whose parents had been born in Ireland. These

people had been in America since birth, but now they were going back to live in Ireland on a permanent basis maybe eighty

years after their parents “got off the boat.” These people are dying to get back to Ireland, a country they see as an appealing

place with a healthy and expanding economy.

Many first-generation Irish-Americans consider themselves (and their future) American. Most of these people visit Ireland

a couple of times and nothing goes beyond that. They are born in America and they, along with their families, will die in

America. They may root for Notre Dame. They may become members of some Irish organizations like the Hibernian Society. They

may buy and read books about Ireland, but they never think of themselves as “Irish.” I would have to fit in this category.

I can’t see Ireland getting so appealing that I go there permanently. Never say never, however.

There is no word in Irish for immigrant or emigrant. The Irish used the word “Jure,” which really means “exile.” “Immigrants”

left their countries because they wanted to. The vast majority of Irish who left Ireland were leaving because they had to.

That, more than anything else, is the Irish tragic moment: the beautiful, perfect place that you have to leave. Wakes are

happy. Departures are sad.

Until fairly recently in Ireland the only economic factor was land. Since the English had permanently taken all the land,

Irish people for centuries were faced with these options: A) Live in poverty and pay the English landlord; B) Make some weapons,

band together, and then kill the English landlord; C) Leave. C was the popular choice—as an Irish person would say, the best

of a bad lot.

You could go to England, the home of your oppressor, you could go to Australia, or you could go to America.

A lot of Irish mythology has to do with the ocean. The white tops of the waves are horses. There is a magic island out there,

the land of eternal youth. Also, way way out there, is America. In the eighteenth century most of the people leaving Ireland

for America were Protestants from the north. By the nineteenth century it was mostly Catholics. But reading about Ireland

is reading about a departing. The songs about leaving and the songs about dying are the same songs.

Ellis Island is a couple of hundred yards north of the Statue of Liberty. Between 1892 and 1954 over ten million immigrants

passed through there on their way into America. There is a good chance that if you are an American, your father

or grandfather or great-grandfather or great-great-grandfather’s first sight of America took place in Ellis Island.

Today there is a museum there. There are lots of artifacts and recorded oral histories and other mementos of coming into America.

There is a big wall, the American Immigrant Wall of Honor, which contains the names of five hundred thousand immigrants. There’s

George Washington and Myles Standish. Nobody named Gannon up there.

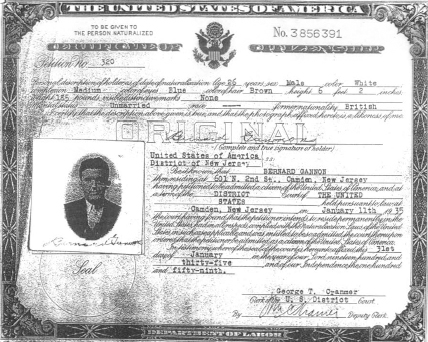

My mom was twenty-three when she became a citizen of the United Stated on April 28, 1932. She listed her former nationality

as “British,” and her race as “Irish.” When my dad became an American citizen, on January 11, 1935, he listed his former nationality

as “British,” but under race he wrote “______.”

This was not that surprising. My dad didn’t like to draw attention to his Irishness. That was something that never changed

with him. I have the documents.

My dad wrote my mom a letter on November 29, 1932. On December 22, 1945, he wrote her another letter. Between those two days

my mom and my dad wrote a lot of letters. Herbert Hoover was president when the first letter was written. By the last, FDR

had just died. The Great Depression ended between the letters, and World War II started and ended. The war ended, the letters

stopped, my mom and dad got married, and, a few years later, I was born.

When my mom died I found the letters. They were kept neatly in a box with string around them. My mom must have kept almost

all of my dad’s letters. I couldn’t find any that she wrote him. The letters my mom wrote would have been much longer. It

was hard for me to picture my dad writing my mom a letter. It was hard for me to imagine him writing a letter to anybody.

If he wrote the way he talked he would have done a lot better with postcards. Since a lot of the letters were written when

my dad was in the army, I can see him stopping and asking the guys in the next bunk, “What can I say now?”

I don’t know what he did with her letters, but my dad moved around a lot when he was in the army, so maybe that’s the reason.

My mom had the same address throughout this period—Ardmore, Pennsylvania, where she worked for a rich, Mainline family, the

Windsors. She helped out around their massive house, and she took care of the children. A lot of Irish girls did the same

thing when they first came to America. A lot of them still do.

I was a little embarrassed for us when I found out that my mom had been a servant for over a decade. I first found this out

when I was thirteen, an age when everything about your parents embarrasses you. My mom wasn’t at all embarrassed. She was

proud of the work she did. She called her job “nurse.”

Because he was in the army when World War II started, my dad’s letters were sent from all over Europe. It must have seemed

ironic to him that he had tried so hard to get across the pond, and now they were sending him back. He never went to Ireland,

although parts of England reminded him of the Old Country. He found France “about the same as Pennsylvania but not as New

Jersey.”