Mind and Emotions (3 page)

Authors: Matthew McKay

This number represents how much your upsetting feelings are affecting your life today, at this moment. This is a baseline figure, so the exact number isn’t very significant. What’s more important is the difference between this number and your score when you do this exercise again, halfway through your work with this book, and your score after you’ve finished the treatment chapters of the book. As you gradually acquire emotion regulation skills, your score will decrease.

Chapter 2

The Nature of Emotions

This chapter examines how emotions work and how they help us survive. It will also give you the tools to observe your emotions and identify the four components of an emotional response. This knowledge will help you recognize how emotions turn into behavior and give you a moment of choice in deciding whether to act on emotion-driven urges.

Unfortunately, the ability to observe and understand emotions isn’t enough to achieve emotion regulation. You’ll have to go one step further and learn to identify the seven dysfunctional coping strategies that fuel negative emotions and trap you in patterns of chronic anxiety, anger, or depression. As mentioned in the introduction, these seven ineffective coping responses are sometimes called transdiagnostic factors because they underlie—and, in fact, cause—emotional disorders.

How Emotions Work

In the course of human evolution, emotions developed for a specific purpose: to spur us toward actions that help us survive. Negative emotions are a signal that something is wrong or threatening and push us to cope. Anxiety pushes us to avoid dangerous situations. Anger drives us to fight back against threats, damage, and hurt. Sadness encourages us to slow down and withdraw, to seek quiet time for processing a loss, or to recalibrate our efforts after a failure. Shame demands that we hide and stop doing what might result in disapproval.

The point is, emotions are useful. They help us change course as we face new problems or new circumstances. They help us adapt to curve balls that threaten to destabilize our lives—or even end them.

Here’s another key point: Emotions, no matter how intense or upsetting, all have a natural life span. If you watch carefully, you’ll observe that all feelings develop like a wave. They rise, crest, and finally recede, and they’re time limited. Seeing an emotion as a wave can help you wait it out, rather than getting swept up in emotion-driven behavior.

When you’re in the middle of an intense feeling, sometimes it seems as if it will go on forever. This is an illusion created by the strength of the emotion, and sometimes by efforts to resist or suppress the feeling. You have multiple emotions each day, and many thousands over the course of your life. Every emotion will end or morph into something else. Learning to be patient, to watch that process, is one of the key skills you’ll gain from this book.

We humans can’t control emotions, meaning we can’t stop them or get rid of them with an act of will. An extraordinary wealth of scientific research has revealed that attempts to suppress, numb, or push away emotions usually fail. What we resist persists. Feelings we attempt to suppress simply go on longer, and often turn into chronic emotional disorders.

To understand how suppression exacerbates and intensifies an emotion, consider the case of a violinist in a volunteer community orchestra who had surges of anxiety during several performances. His response was to do everything possible to control the feeling, including constantly watching for the first signs of sweating or a rapid heartbeat. But the effort not to feel anxious only focused his attention on the symptoms of fear. If he detected any sensations that might indicate fear, he tried to control the experience through avoidance—to the point where he started to think he wouldn’t be able to perform if he felt fear—and that was a really scary and upsetting thought. The more he paid attention to his body and watched for anxiety during a performance, the greater his fear became. So remember: You can’t stop emotions, and some efforts to control them will only make them worse.

Components of an Emotional Response

An emotional response is a lot more than a mood state or a feeling. It has four components, and it’s important to understand and recognize each of them: affect, emotion-driven thoughts, physical sensations, and emotion-driven behavior.

Affect

The most obvious part of an emotion is the

affect

: your conscious, subjective experience of the feeling itself, apart from bodily changes. The affect is what people commonly label as “sadness,” “fear,” “anger,” and so on. Affect is generated in the limbic area of the brain and produces what psychologists call a drive state—an urge to some kind of action, such as withdrawal, flight, or aggression. Negative emotions create a sense of distress and disequilibrium—a sense that things aren’t right and need to be fixed. The affect part of these emotions is designed to get our attention, to make us realize that there’s a threat or an imbalance that requires action.

Emotion-Driven Thoughts

The second component of an emotional response is what happens cognitively: thoughts about a situation in which we find ourselves or about the emotion itself. Thoughts during an emotional response tend to fall into two categories: prediction and judgment. Prediction is an attempt to peer into the future and see what dangers might lie there. Predictive thoughts usually ask the question “What if?”: “What if I lose my job?” “What if the pain in my stomach is a tumor?” “What if my son doesn’t get into college?” Predictions prepare us for what might happen, but they also have the effect of triggering anxiety as we attempt to solve a problem that hasn’t even occurred—and may not ever occur.

Judgments can be directed toward the self or others. When they’re directed toward the self, judgmental thoughts produce sadness and depression. When they’re directed toward others, they tend to trigger anger. Either way, a judgment conveys a belief that the object of that judgment is wrong, bad, mistaken, and somehow guilty of breaking the rules for reasonable living.

Emotion-based thoughts are part of a feedback loop that can both trigger and intensify affect. Predictions and judgments can literally create emotions, and then the surging feelings that result can produce a new flurry of negative thoughts that further escalate the emotion.

Physical Sensations

Every emotion has a physiological component. Emotions are felt in the body. Anxiety elevates your heart rate, speeds up your breathing, and can make you sweat, shake, and tense your muscles. Depression generates feelings of heaviness, torpor, and exhaustion. Anger produces sensations of heat, along with tension in your arms and legs as you get ready to fight. Shame produces a feeling of being flushed, weak, and sometimes almost paralyzed.

Like emotion-based thoughts, the physical sensations that accompany each emotion can contribute to a feedback loop that strengthens the affect. For example, the palpitations and sweating that accompany anxiety seem to make feelings of fear worse. You say to yourself, “My heart’s pounding like a trip-hammer. I must be scared as hell,” and the fear intensifies.

Emotion-Driven Behavior

The last component of an emotional response is the action urge. Action urges always accompany feelings. Anxiety makes you want to avoid. Depression makes you want to withdraw. Anger makes you want to be aggressive. Shame and guilt make you want to hide.

When you let yourself act on emotion-driven urges, they fuel the emotion rather than regulate your feelings. While there is some survival value to these urges, engaging in emotion-driven behaviors frequently tends to convert episodic emotional experiences into chronic problems. There is abundant research showing the more you avoid anxiety, the more anxious you become (Eifert and Forsyth 2005), and withdrawing when you’re sad makes depression worse (Zettle 2007). There are also studies showing that the more aggressive your response to anger is, the more easily you’ll get angry (Tavris 1989). So emotion-driven behaviors may help you cope with difficult things in the short term, but if you engage in them habitually, they play a huge role in emotional disorders.

Exploring Your Emotional Responses

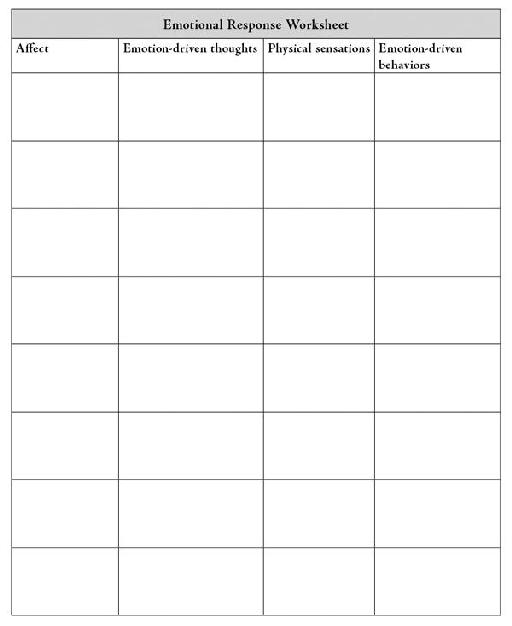

Now it’s time to explore your own emotional responses. The following Emotional Response Worksheet will help you separate your feelings into the four components just discussed: affect (the emotion), emotion-driven thoughts, physical sensations, and emotion-driven behaviors. Over the next week we’d like you to use this worksheet to identify and clarify your emotions. Make copies of the worksheet and keep one with you at all times, leaving the version in the book blank so you can make more copies as needed (you’ll use this worksheet in the next exercise too). Each time you feel an emotion during this period, name it in the left-hand column, under “Affect.” In the next column, “Emotion-driven thoughts,” write down any judgments or predictions that occurred as you experienced the emotion. In the “Physical sensations” column, record any feelings in your body that accompanied the emotion. And finally, under “Emotion-driven behaviors,” write down any action urges (whether you actually did them or not) that you felt during the emotion. If you aren’t sure how to fill out the form or need a little help getting started, we’ve provided a sample worksheet.

Using Music to Explore Your Emotions

This exercise will help you gain familiarity with your emotional responses, and perhaps feel more comfortable with them. The exercise calls for listening to emotionally evocative songs, so the first step is to identify six or eight songs that have an emotional impact on you. Think of music that really moves you and seems to open something emotional within you. Ideally, the various songs shouldn’t trigger the same feeling. Some of them might evoke sadness, some might make you feel hopeful or excited, and some might even make you feel angry.

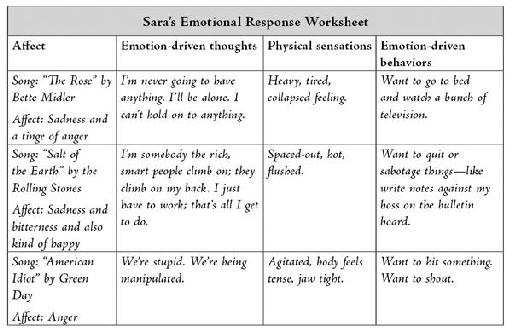

Over the next week, play each of these songs at least once. Then, on the Emotional Response Worksheet in the preceding exercise, explore this music-generated affect alongside any other emotions you’re recording during the week. As you listen to each song, turn your attention fully to whatever emotions you feel and try to keep them at the center of your awareness. Whether an emotion is painful or pleasant, look for words that really capture the essence of the feeling. Name the emotion, perhaps also describing some of the nuances or subtleties of the experience. In the appropriate columns, write down any thoughts, sensations, or action impulses that arose while you were listening. Again, here’s a sample to give you an idea of how to fill out the form.

Building Emotion Awareness

In this exercise you’ll visualize events from the past to intentionally and temporarily bring on stronger emotions so you can learn about them. Right now, look back over the past six months to a year and identify three different events: one that triggered anger, one that triggered sadness, and one that caused anxiety. On a separate piece of paper, write a description of each situation, including where you were, whom you were with, and the basics of what happened.