Mira's Diary (15 page)

Authors: Marissa Moss

It took a while to find the hotel Zola mentioned, but Serena Goldin had already checked out. Was Mom still here or somewhere else, some

when

else, completely? Or had Madame Lefoutre found her and done something to her? I wished I could get back to Dad and Malcolm and get their help. I touched every fountain and sculpture I passed, but I was still stuck in this time.

At least Zola wrote the article. It came out today, with the big bold headline blaring “J'Accuse!” or “I Accuse!” It sounded better in French than in English, but either way, it was a finger pointing directly at the corruption of the military and those in the government who had helped with the cover-up.

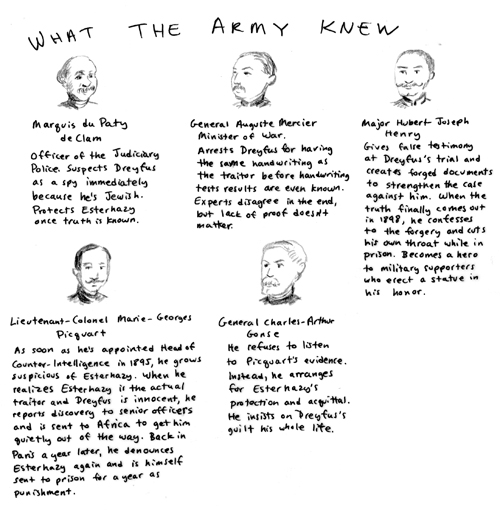

In the article, written as a letter to the president of the French Republic, Zola laid out clearly how the military had rushed to accuse Dreyfus since he was Jewish, and how, once he'd been blamed, they couldn't go back even when his innocence was clear and so was Esterházy's guilt. The honor and image of the military was more important than one man's torture. And having chosen that deal with the devil, the military also punished anyone who got in the way.

After showing how corrupt the military had been, Zola wrote a rousing call for justice. I copied it (with thanks to Mary Cassatt for her expert translation).

“It is a crime to lead public opinion astray, to manipulate it for a death-dealing purpose. It is a crime to poison the minds of the humble, ordinary people, to whip reactionary and intolerant passions into a frenzy while sheltering behind the odious bastion of anti-Semitism. France, the great and liberal cradle of the rights of man, will die of anti-Semitism if it is not cured of it. It is a crime to play on patriotism to further the aims of hatred.”

Then he ended just the way Malcolm wanted him to:

“I have but one goal: that light be shed, in the name of mankind which has suffered so much and has the right to happiness. Let them dare to summon me before a court of law! Let the inquiry be held in broad daylight! I am waiting.”

Dad once told me about the Watergate hearings, which happened when he was in high school, how the president of the United States had sent “burglars” into Democratic campaign headquarters so he could know about the competition's plans for the presidential election. The whole country was riveted by the congressional hearings into who had done what when, and how far up the chain of command the blame went.

The buck went all the way to the President, Richard Nixon, who had to resign or face being impeached for his crimes. Dad said that even as a high school student, the first thing he did when he came home from school was turn on the TV to watch the hearings. They were more dramatic than any spy movie he'd ever seen.

That kind of public attention and public uproar was happening in Paris. There were demonstrations for Dreyfus, against Dreyfus, for the military, against the military. Esterházy was burned in effigy before the Hôtel de Ville, the Paris city hall. And so was Dreyfus.

It was exciting, dramatic, and totally scary. I didn't know what I was supposed to do or where Mom was (except not in her hotel). Zola had lit the match. The truth was definitely out there, so why did I need to still be here?

I climbed the stairs to the gargoyle gallery at Notre Dame where this had all begun. Looking down at the city, I could see mobs swirling up and down streets. In one plaza, a man on a box was shouting slogans to a crowd around him. In another, piles of newspapers and books were burning, Zola's accusations turned to ash and smoke.

Was this what was supposed to happen? I wished Mom was here, that she could tell me it was all right, and she'd be home soon. It didn't feel right. In fact, it all felt very wrong.

The gargoyles looked down blankly on the frenzied streets. They'd seen much worse, I bet, including the French Revolution when people were guillotined in the public squares, something much more brutal than a pyre of newspapers. The sharp-beaked gargoyle eating the chicken creature still creeped me out, but I couldn't stop myself from reaching out to touch its head.

And just like then, the world buzzed with a strange staticky sound, the days and nights whirled around me, and I was back where I'd begun this whole weird tripâin 2012. Or if not that exact year, modern times, because looking down from the gallery, I could see that the streets were clogged with cars and buses, streams of tourists, and the occasional bicyclist fighting their way through. Were all the gargoyles touchstones? I was afraid to even brush against one, now that I was back in the time where I belonged. I skirted past an enormous German and plunged down the stairwell, eager to get back to my family.

Where were Dad and Malcolm, though? Were they back at the Eiffel Tower where I'd left them?

Since the hotel was close by, I decided to check there first. The good news was that not only did we still have rooms there (the right time!), but Dad and Malcolm were actually in them.

“Mira!” Dad hugged me. “Where were you? What happened to you?”

“So this time you noticed me going?” I asked.

“Of course we noticed! We looked for you everywhere! We came back here thinking you'd find us, rather than the other way around.”

“And that worked,” I said, suddenly exhausted, plopping down on the bed.

“So where were you? Where's Mom?”

I wished I had the answers Dad wanted, but I didn't.

“Does that mean she didn't succeed? She didn't do what she needed to?” Malcolm asked. He didn't add “and you didn't do it either,” but I knew he was thinking it. We all were.

“Zola wrote the story Mom wanted,” I said. “But maybe it didn't make the difference she thought it would. I wasn't there long enough to know. Did Dreyfus get a second trial? Was his name cleared? Was Esterházy ever convicted? And what about all the officers who framed him and covered up the truth?”

Dad looked at Malcolm. “Do you know what happened to Dreyfus?”

“And what about Zola?” I asked. “Why did he expect to be put on trial? What was the inquiry he said he was waiting for?”

“I don't know,” Malcolm admitted. “We'll have to look things up again. That's the only way to know if you guys did what you were supposed to do anyway.”

We headed for the Internet café again. It didn't seem to matter that we were in Paris, the most romantic city in the world. All we'd seen were Notre Dame and the bottom of the Eiffel Tower. And the Internet café.

“Did you guys go up the Eiffel Tower? Did you get some good photos, Dad?” I hoped they'd had some fun at least.

“I took some decent pictures, but we were looking for you so we lost our place in line. That's okay, we'll do it again, all three of us. Maybe all four of us even,” Dad said hopefully.

Maybe all I'd get out of Paris was what I drew in my sketchbook. I let Malcolm look stuff up on Wikipedia while I sketched outside, imagining Claude drawing beside me.

What Malcolm found wasn't happy news. “Dreyfus did have a second trial, but despite the overwhelming evidence of his innocence, he was still found guilty. But because of Zola and the frenzy that his article started, the French president pardoned Dreyfus so he was freed. Wait, there's more⦔

“At least you got him off Devil's Island,” Dad said. “That's something.”

“I didn't do that. Zola did. And it wasn't enough.”

“Zola wouldn't have written the story without you.”

“You mean without Mom. We both gave him information.” I should have felt proud, but I didn't. Not without Mom.

“Dreyfus was finally exonerated,” Malcolm said, “but not until 1906! By then, there was a general amnesty clearing anyone in the military who framed him. So they basically got away with it.”

“What happened to Zola?” I asked Malcolm, expecting the worst.

“That's not good either.” Malcolm squinted at the screen and summarized the bad news, “Zola was tried for libel, and the military, of course, lied againâand again and again. And since Zola wasn't allowed to introduce evidence about the truth of what he wroteâthe name of Dreyfus wasn't permitted to be even mentionedâthere was no way for him to prove his case. It wasn't a trial, it was a total joke, but the mob hysteria Zola had written about showed up in full force at his trial. He received death threats. Crowds threw rotten vegetables at him, yelling âDrown the Jews! Long live the army!'” Malcolm turned to look at me. “Were people saying that kind of stuff to you?”

“Only Degas,” I said. “Well, not really. But he made it clear he had no use for Jews, so you can see how well I did with that bagel-selling job you recommended.”

Anyway, Zola wasn't Jewish, but he'd spoken up for the Jews and that was enough to label him one. He was stripped of his Legion of Honor status and sentenced to the maximum penalty, a year in prison and a fine of 3,000 francs. To escape prison, he fled to London, an exile from his own country. While he was gone, his property was sold by the government to pay the fine.

I felt awful for Zola. I'd convinced him that he should take the risk, and he was punished for it. As was everybody who had tried to help Dreyfus. And what about Mom? Had she been punished too? Had Madame gotten to her? I had to go back and find out. I had to find her.

Malcolm had other ideas. He suggested we go see Zola's grave in the Montmartre Cemetery.

“I didn't know how great the guy was,” he said. “Seems like the least we can do is put some flowers on his grave or something. Right, Dad?”

“Sure, and we'll see a different part of Paris too. Montmartre is supposed to be especially charming.”

I smiled. “I know that neighborhood pretty well. Let me give you a tour.”

So we finally did something like regular tourists. I showed Dad and Malcolm where Degas used to live, Mary Cassatt's and Renoir's homes, the café where everyone hung out.

It was strange seeing all these places in modern times, with cars parked on the paved streets, electric streetlights, parking signs, trash cans, bus stops, all the things that weren't there in the nineteenth century. But some things stayed the same, like the streets themselves.

“You really were here, weren't you?” Malcolm gaped at me. “I mean, you know this neighborhood. You know where you're going.”

“Give me a little credit. I may not know history, but I have a pretty good sense of direction.”

“It's just hard to really believe it all,” Malcolm said. “You met Degas! And Zola!”

“Too bad convincing Zola to write his article wasn't enough.”

“Why do you say that?” Dad said. “You made a tremendous difference.”

“No,” I disagreed. “Because if things were fixed, then Mom would be back with us.”

We walked through the cemetery, which was like a little town itself with graves built like small houses and elaborate sculptures. Usually I like cemeteriesâI'm weird that way. I find them peaceful and pretty, kind of like gardens for dead people. And although this was an especially nice cemetery, I didn't feel peaceful at all.

“This is it!” Malcolm called, pointing out a bronze bust set into a marbled stage. It was Zola's grave, magnificent and important, just like the man had been.

“Looks like he got the recognition he deserved in the end,” Dad remarked. “This is hardly a shy little nobody's grave.”

Malcolm laid the bouquet of bright daisies we'd brought onto the stone under the bust. “I'd like to think I'd stand up for what I believe the way you did,” he said to the sculpture.

I wanted to think that too. Would I? Was I brave enough?

There's a Jewish tradition that when you visit someone's grave, you leave a stone on the marker. I found a smooth gray pebble and set it on Zola's tomb. “Thank you,” I said. “For Dreyfus and for all Jews. For everybody who believes in justice.” I touched the brown marble lightly. “Thank you.”