Miss Ellerby and the Ferryman (13 page)

Read Miss Ellerby and the Ferryman Online

Authors: Charlotte E. English

Tags: #witch fantasy, #fae fantasy, #fantasy of manners, #faerie romance, #regency fantasy, #regency romance fairy tale

‘Thou

hast the manners of a swine,’ the giant informed Balligumph.

‘Motley-minded and a miscreant, troll! A reeky, knotty-pated

malt-worm!’ He glared down at the troll, who was laughing

uproariously at this barrage of insults, and added, ‘I was but two

instants from forming the most perfect leaf I have sculpt’d in all

the long ages of my life.’

Balligumph swept off his hat and bowed low to the giant. ‘My

apologies, then! I am sure ye will make more.’

The

giant’s glare vanished, and abruptly he grinned. His eyes were

jewel-green and they began, now, to twinkle; his leathery face

wrinkled further as he grinned. ‘Miscreant!’ he repeated. ‘Thou art

a plague upon giant-kind.’

Balligumph nodded agreement. ‘That I am, an’ an honour it is

to be so.’

The

giant’s gaze moved past Balligumph, and settled upon the rest of

his party. ‘A merry band of travellers! Wherefore hast thou

conveyed such colourful folk hither?’

‘Tis

yer help we’re after,’ Balligumph said. He motioned the riders

forward, and gestured for them to dismount. Isabel found herself

standing almost upon the protruding roots of the violet-decked

tree, and carefully avoided them, for what if they were all

giants?

‘This

is Sir Guntifer,’ Balligumph said, beaming. ‘One o’ my oldest

friends, when he is not slumberin’ like an old

lazybones.’

‘I am

an old lazybones,’ interjected Sir Guntifer.

‘Well, an’ I was bein’ charitable,’ said Balligumph. ‘But if

ye prefer, I will tell the truth. A more frippery fellow ye scarce

‘ave met in yer lives, an’ lazy to boot. But he is loyal, an’

clever, an’ he knows more about anythin’ ye can think up than

anyone.’ His grin widened. ‘Even me.’

Isabel’s brows rose as Balligumph spoke of his friendship

with the giant, for the insults they had hurled at each other were

fresh in her mind. There was no mistaking the gleam of affection in

Sir Guntifer’s eyes, though, as he looked at the troll; nor the

true geniality of Balligumph’s smile.

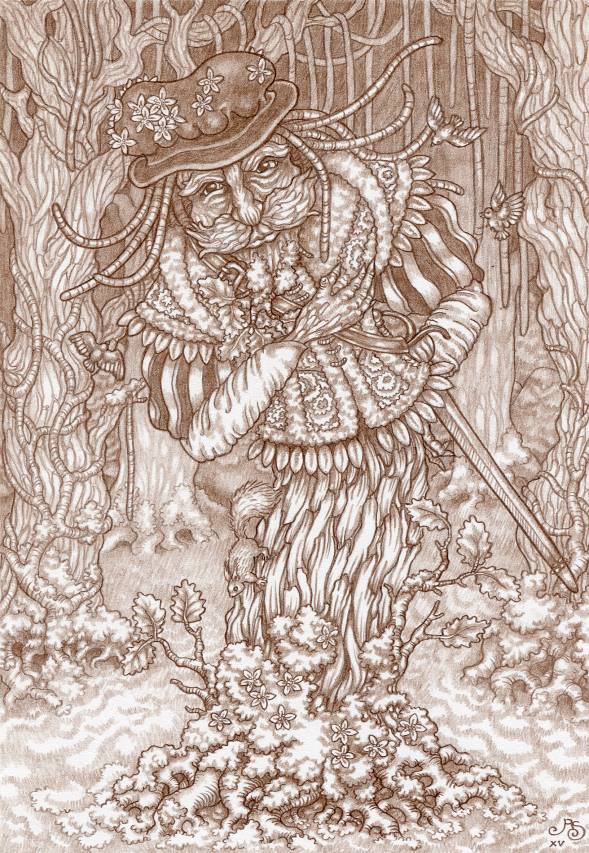

The

tree-giant’s form began subtly to alter once more, and soon he

stood a giant entire, his trunk gone in favour of stout legs in

tall boots up to the knee and laced britches the colour of oak-tree

bark. He carried a weapon like a rapier at his side. He took off

his hat, from the brim of which sprang a cluster of tumbling vines

finer than any feather, and swept them another bow. This was still

more fluid and flamboyant than the first, displaying the grace and

manners of a courtier. Isabel stared, astonished, and only

belatedly remembered to curtsey in response.

‘Fine

folk,’ pronounced Sir Guntifer, restoring his hat to his head. ‘I

am Sir Guntifer Winlowe! Once I was guard to the Royal Family of

Aylfenhame, in lost and thrice-mourned Mirramay. Now, I am as you

see me: slumbersome and adrift.’

‘An’

a trifle melancholy,’ said Balligumph, patting Sir Guntifer gently

on the back. ‘But ‘tis just because ye ‘ave been asleep too long.

Ye’ll rouse. An’ I have a task to help ye along.’ He grinned and,

with a swift glance at Lihyaen, added, ‘Nigh on a century, no?

P’raps more? A fine, long rest.’

Lihyaen had become visibly more alert at this mention of the

Royal Family, and no wonder, for the possibility that he might have

known her parents immediately presented itself. Perhaps he even

knew what had become of her father — or the person who had taken

Lihyaen herself! But at Balligumph’s shrewd words these hopes faded

and she settled once more. One hundred years and more was far too

long ago; when the king had vanished and the queen had died, Sir

Guntifer must have been asleep.

‘Very

well,’ rumbled Sir Guntifer. His voice was very deep and rough,

like tumbling rocks. ‘Pray you, then: tell me of this

errand.’

Balligumph took off his hat and scratched at his head,

frowning. ‘Did ye ever have cause to make use o’ the

ferries-as-was?’ he said.

Sir

Guntifer shook his head. ‘Nay, I had nought to do with the

Ferry-folk.’

‘But

ye’ll remember Kostigern, I’ll wager.’

Sir

Guntifer’s face darkened. ‘Aye. That I do.’

‘In

the wake o’ that, every one o’ the Ferries was disbanded — all save

one, an’ its Keeper was cursed t’ toil upon it forever. Can ye

recall word o’ such?’

‘The

Last Keeper.’ Sir Guntifer peered at Balligumph. ‘What is the

nature of thy business with such as he, old friend?’

‘It

don’t sound as ye like the fellow overmuch,’ Balligumph

commented.

Sir

Guntifer shrugged his wide shoulders, sending puffs of moss and

dirt into the air. ‘Ne’r have I met the Keeper, but tidings of him

reached me in ages past.’ He paused, frowning. ‘Tis his merited

punishment, some say, for his support of the one called Kostigern

in the Times of Trial.’

Isabel opened her mouth to object, but caught herself in

time. Support of Kostigern, the traitor? Remembering the Ferryman’s

congenial manner, his kindness, and above all his loneliness, her

heart cried out at the allegation. But good sense intervened before

she could make a fool of herself. What did she know of the

Ferryman, in truth? Little indeed. A mere hour’s conversation with

a man she found pleasant could not render him incapable of

wrong-doing. But the thought troubled her.

‘Aye,’ Balligumph was saying. ‘I ‘ave come across such tales

me own self. I dunnot know if there’s a scrap o’ truth in ‘em.’ He

glanced at Isabel as he spoke, and she was warmed to detect a note

of concern in his eyes — warmed and embarrassed, for had her liking

for the Ferryman been so obvious?

‘Ye

don’t know, then, how the curse came t’ be bestowed, or by who?’

Balligumph continued.

Sir

Guntifer shook his head. ‘That is not known to me.’

‘An’

therefore, ye don’t know who he was before he was the

Ferryman.’

Sir

Guntifer shook his head again. ‘I would that it were not so, for I

see I am of no help to thee.’

Balligumph sighed, his shoulders slumping. ‘I ‘ad hopes,’ he

admitted. ‘Tis said tha’ to lift the curse his name ‘as to be

found. I was hopin’ ye might know, old as ye are.’

The

giant stuck a vine into his mouth and chewed upon it. ‘Mm,’ he

said.

‘Tis

a thorny problem.’

‘Verily.’ The giant thought some more. ‘Wherefore dost thou

wish the Ferryman’s freedom?’ he enquired. ‘He may be a foe, but if

he is not that, he is certainly no friend.’

‘The

young lady,’ said Balligumph with a slight cough and a gesture

towards Isabel, ‘is possessed of a heart o’ gold, an’ she has made

somethin’ along the lines of an unwise promise to the

lad.’

Sir

Guntifer’s gaze settled upon Isabel, and she found herself surveyed

with discomfiting keenness. ‘Has she,’ he said.

Isabel looked at her feet, colouring. Never had she felt so

foolish as she felt now, speared by that intense, ancient gaze. She

felt that every part of her folly was displayed to his discerning

eye, without hope of respite. ‘I felt…’ she began, but her words

died away.

‘Ye

felt?’ prompted Balligumph. ‘Come now, lass. Ye’re among friends.

Ye must tell us everythin’, the better we’ll be able to help

ye.’

Isabel lifted her chin. ‘I felt sympathy for his plight,’ she

said. ‘No one deserves such a fate, and I do not care what he has

done.’

‘Some

people do,’ muttered Aubranael, and Lihyaen nodded. If they were

thinking of the one who had taken Lihyaen, then she could not

disagree; but the possibility that the Ferryman was capable of such

villainy seemed, to her, utterly impossible.

To

her relief, Sir Guntifer smiled upon her, and even patted her upon

the head — crushing her bonnet entirely, she feared. ‘A sweet

maid,’ he said. ‘I hope for thy sake, little one, that he is worthy

of thy belief in him.’

‘Me

too,’ growled Balligumph.

Sir

Guntifer stretched mightily, and shook himself. ‘If it were some

two centuries ago at this moment,’ he said, ‘I would say that the

Chronicler is the person who would know. But thou art late

indeed.’

Balligumph’s eyes brightened. ‘The Chronicler! I heard word

o’ him, once upon a time. Royal record-keeper, or some such, back

in the golden days o’ the Royals?’

‘Aye,’ said the giant. ‘Every event of note went into his

books, and he knew all. But he is gone. Gone since

Kostigern.’

‘Gone?’ said Balligumph. ‘Or destroyed?’

‘That

is not known.’

A

wide smile split Balligumph’s face. ‘Ye were gone an awful long

time,’ he said to Sir Guntifer.

The giant raised

a shaggy eyebrow.

‘Come

t’ think of it, the Ferryman was also scarce fer the odd decade or

two.’

‘Aye,’ said Sir Guntifer. ‘Thou art thinking that, mayhap, the

Chronicler has also returned.’

‘There’s a slim chance, do ye not think?’

‘Slender indeed.’

‘Thin

an’ feeble an’ scarce worth the name o’ hope, but a chance! Now,

I’m thinkin’.’ Balligumph tugged his hat from his head and began to

turn it about in his hands, pulling at the brim and chewing upon

his lips as he thought. ‘Last seen in Mirramay, most like?’ he said

at last, looking at Sir Guntifer.

‘Aye.’

‘Then

to Mirramay ye must go!’ Balligumph stuck his hat back onto his

head and tapped upon it with a pleased smile. ‘Lots goin’ on in me

noggin,’ he announced. ‘The Missie, now. She’s ‘ere fer

witch-trainin’, ain’t that the truth? Well, so. Send ‘er to

Mirramay wi’ the right sort o’ companions an’ she’ll get all the

trainin’ she’ll need — an’ a mite of perspective, like. Maybe

she’ll find the Chronicler there an’ maybe she won’t, but a great

deal may happen on such a journey. A very great deal.’

Balligumph concluded this speech with a wise nod and a

beaming smile at Isabel, who involuntarily stepped back a pace.

‘Mirramay!’ she said. ‘Gracious me, I really… that is, I have not

the smallest notion where that may be. Or what manner of place it

is.’

‘Not

a worry!’ said Balligumph promptly. ‘Ye will have a guide. It is

the largest an’ finest city in all of Aylfenhame, an’ the site o’

the Royal Court.’ His smile faded into a scowl, and he shrugged.

‘Or it was. ‘Tis all broken down, now, in the absence o’ the Royal

family.’

Isabel glanced uncertainly around at her companions, seeking

signs of enthusiasm for this plan. They looked as blank as she,

though Lihyaen wore an expression of intent interest. ‘Is it very

far away?’ Isabel asked.

‘Oh,

a deal o’ distance,’ said Balligumph with unimpaired

cheer.

‘Then

surely I cannot. I am here without my Mama’s knowledge, and before

long I must return to England.’ She blushed with shame at owning

such a piece of misconduct and deceit, though it had been embarked

upon at her aunt’s urging — and more than urging. But nobody looked

shocked at such an admission. If anything, the sparkle in Sophy’s

eyes denoted approval.

‘Yer

Ma will manage without ye fer a week or two,’ said Balligumph. ‘An’

ye may trust yer aunt to take care o’ such matters as

that.’

‘She

cannot conceal my absence forever!’ Isabel protested. ‘Nor explain

it, once it is discovered! I must not place her in such a difficult

position.’

Balligumph grinned. ‘Seems to me yer aunt ‘as more put ye in

a difficult position, an’ fer good reason. Don’t ye worry yer ‘ead

about Eliza Grey. She is more than equal to the challenges, an’ it

was ‘er own doin’ at that.’

Isabel’s mouth opened, but no further objections spilled

forth. Not because she was disinclined to make any, but because she

could think of no further reasons to refuse, besides her own deep

reluctance to undertake any such journey. She ought to be paying

morning calls with her aunt and attending York assemblies, not

gadding about in Aylfenhame! Besides, how was she to manage such a

journey? She was not so physically robust as Sophy, and it would

surely be arduous.

‘I

will go with you,’ Sophy said, her voice pitched low. It was

typically considerate of her. Not for the world would she loudly

push Isabel into any scheme she disliked, but she would always

support her if her help was required. Isabel smiled gratefully at

her.