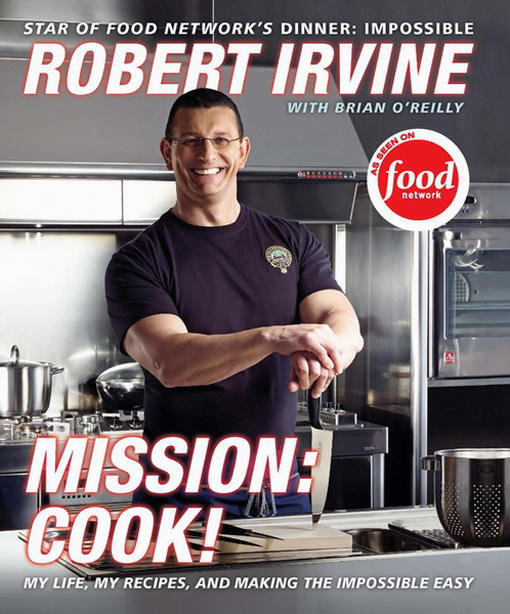

Mission: Cook!

Cook!

My Life, My Recipes,

and Making the Impossible Easy

With Brian O'Reilly

I

HAVE NO IDEA WHERE I AM GOING.

It's not for an immediate lack of direction or information. I am driving to my

immediate

destination in the middle of the night from an appearance at a live cooking event in Morristown, New Jersey. I am driving a sleek new BMW with a technologically advanced GPS system, into which I have fed the coordinates for a hotel in Princeton. In the short term, I think I am probably quite close to that locale. I am hoping to get some food and at least a few hours' rest before the big day tomorrow. Therein lies the mystery.

Tomorrow, I am due to arrive at an undisclosed destination, where I will be cooking for an indeterminate number of people I have never met, in a kitchen I have never seen, with stores of food and ingredients that may or may not be of my choosing. I have no idea how long I will be given to accomplish this task, nor will I have any prior ability to plan ahead in even the smallest detail. And I have willinglyâ¦no, eagerly, placed myself in this predicament.

There is only one force that could be responsible for devising such an absurd situation with such a markedly high potential for disaster:

television.

Tomorrow is the day I am shooting the pilot for my first (hopefully successful, hopefully the first of many, fingers crossed) Food Network show. Each episode of the show will feature your humble servant, me, ably assisted (most of the time at least, God and my sadistic producers willing) by my incredible souschefs, George and George, in equally absurd and improbable cooking situations, with

no advance warning

or information ahead of the game as to where, how, for whom, and with what we might be cooking at any given time.

Pretty cool, huh?

I am not inherently of an existential bent, but it's hard to avoid a certain level of reflection on one's life when a benchmark for a long-sought and cherished goal such as this has been reached.

As you will see in the succeeding pages, I am a bit of an anomaly in the cooking trade. Although I have a wide-ranging acquaintance with classical technique and world cuisine, I have never been to a formal culinary institute or cooking school. I am equally at home cooking for six people at a time as I am for six thousand, and I discovered that ability within myself whilst I was still in my teens. I have cooked an inordinate proportion of meals in my career on the ocean. I have had the privilege of cooking for royalty, celebrities, politicians, and ambassadors of high rank, diners of every stripe, but unlike, say, Thomas Keller and his most admirable French Laundry, I have neverâyetâestablished a single restaurant kitchen as my home base.

In more than a quarter-century of cooking, I have never settled down, professionally speaking anyway. Not unlike the freelancers of medieval European chivalry or cowboys for hire on the open range in the American West, I have preferred to follow my own path, my own internal compass. I have never liked being constrained within a single system or style of cooking, and I have always looked to the next horizon for opportunity and inspiration.

I am very good at drawing up strategies and attacking problems, but in general, I don't like “plans.” Blueprints, manuals, corporate directives, and even recipes essentially leave me cold. I have collected cookbooks from about the age of eleven, and have always enjoyed studying the pictures and figuring my own methods for achieving a dish more than slavishly following every measurement and cooking time listed by the author.

I believe that cooking can be a demonstration of what you have inside of you, whether you are a chef expressing a passion for exquisite culinary detail, a cook dishing up hearty and delicious fare in a diner to fuel your customers for the day ahead, or a mother expressing love and caring for her family at the dinner table. I believe that these feelings are best expressed

in the moment.

I have created a lot of dishes with which I am quite pleased, that reflect my basic philosophies of how to put a dish together. I try to use fresh and interesting ingredients, to incorporate the element of surprise, ofttimes by combining hot and cold items on the same plate, by pairing unusual textures, by building the dish on the plate in a new and interesting way, all without sacrificing the integrity of the whole. But however well practiced and well calculated a dish might be, I know that I will never make it the exactly the same way twice. I may find a novel ingredient whilst passing a market on the way to the event and throw it into the mix; I may be in a bad mood and thus decide to approach the same old dish in a new and playful way to cheer myself up; it may be rainy, or sunny, or Christmasyâall of these will affect the way I cook on the day. If

I know my audience personally, it changes the plan of attack I might use for an anonymous crowd. If I make a dish tomorrow instead of today, well, that changes everything.

The more open you are to the world and its infinite variety of people and influences, the more they will spill into and around your life. This television opportunity came from totally unexpected sources, and I find myself relishing this next challenge, because, in fact, it suits me. I probably would not have purposely chosen a format in which I will never have any idea what might be coming at me next, but I can already see that it is going to test me and my particular theories about cooking and life in ways that could prove deeply satisfying (if I don't screw up too much). Though I don't believe in recklessness, which carries its own punishments, I do believe that spontaneity is its own reward. One of the biggest rewards is creative satisfaction. The biggest, in my opinion? It makes things a lot more fun.

I also believe in sharing what I have learned; thus this book. There are stories contained herein about how I got to where I am, collaborations and conversations about how to approach and think about the subject of food, and recipes that I think and hope you will enjoy. Make them if they appeal to you, see how they work, and then, please take the liberty of making them your own and using them as a jumping-off point for inspiration. Some of these recipes apply directly to the stories in this book; some of them demonstrate certain qualities that are valuable to the study and discussion of food; some go together thematically, some don't; some are just in there because they're

good

and I thought you might like to give them a try.

A good chef knows how to set the tone for a meal by provoking interest with a taste of things to come that illustrates, ideally, what his cuisine is all about in a single bite or two. The

amuse-gueule,

which literally is an “amusement for the mouth,” is a very small chef's tasting, offered upon seating, of a preparation that is exotic, surprising, or special, to prime the palate for what is to come. The amuse-gueule can tell you a lot about the chef and about what he is preparing to set before you. Seems like a good way to start a book, too.

AMUSE-GUEULE, TIMES TWO

Adventurous tales of two Roberts, from civil war in

South Yemen to the red carpets of Hollywood

“T

HEY MUST BE FED.

”

It is this phrase, simple and elegant in its clarity and concision, that comes most prominently to mind when recalling the events of the civil uprising in South Yemen and the details of one of the most unusual and consequential meals that I have ever been called upon to prepare.

I was all of twenty years old, was serving in the Royal Navy, and sailing en route to New Zealand aboard Her Majesty's Yacht

Britannia,

Her Majesty being Elizabeth the Second, Queen of England, and I being Robert Irvine, Royal Yachtsman and a leading cook aboard ship. Our intended mission was to rendezvous with the Queen and her entourage following a planned state visit to that country.

HMY

Britannia,

commissioned by King George VI to replace the royal barge

Victoria and Albert III

in 1948, was, simply put, a floating palace. We sailed the seas of the world in splendor, cleaning and polishing, cleaning and polishing, and, I, of course, cooking. My responsibilities included everything from afternoon tea for the duke of Edinburgh and his estimable wife, to lavish banquets for heads of state and celebrated passengers from every continent, all served at the pleasure of the Windsors, the Royal Family of England. The

Britanni

a was richly appointed stem to stern, yet its warm teak decks and paneling, its chintz-covered sofas, deep armchairs, and surprisingly homey appointments, such as the baby grand piano and electric fireplace in the drawing room, the personally favored paintings and family pictures, spoke more of comfort than of regal extravagance. Indeed, Her Majesty was known to have said that she really only felt at home on that splendid vessel. Make no mistake, the Royal Yacht was royally provisioned with the world's finest in china, silverware, linens, and crystal. The food stores on board were always of supreme quality, from the very pinnacle of English beef, the freshest seafood, vegetables, and accompaniments, to every manner of caviar and foie gras, to the tiniest

morsel of excellent shortbread for tea. All in all, it was a wonderful place to entertain, sip a gin and tonic, and escape from the weighty responsibilities of the modern monarchyâ¦but not today.

I had been summoned to the bridge moments before and informed that we were to be diverted from our present course in a “relief effort.” I was to take stock of the provisions we had on board that could be landed ashore quickly and efficiently. No further details were immediately forthcoming, nor did I expect there to be. Life was simpler then; we went where we were sent, and were expected to perform our assigned duties to the best of our abilities and beyond, when and wherever required.

In truth, my superiors hadn't many more details to pass along. The governments of many concerned countries, most prominently Britain and Russia, had been caught unawares by the rapidly spreading civil uprising in South Yemen. At the center of the conflict was a dustup between the besieged current president, Ali Nasser Muhammad, and the disgruntled former president, Abdul Fattah Ismail, who was tenaciously assailing the capital with his band of rebels. Thousands had been killed, the shelling was ongoing, and British civilians stranded in Aden, the capital of South Yemen, had been instructed by BBC announcers in London to assemble in “the northeast sector of the Sovietembassy compoundârepeatâthe Soviet-embassy compound, from which you will be taken to the beach for evacuation.” Which was exactly where we were headed, apparently to prepare lunch.

In transit to the port of Aden, there was little time to plan or strategize. We rendezvoused with other British naval vessels, including the heavily armed frigate HMS

Jupiter.

The

Jupiter

was not allowed to sail within the twelve-mile territorial limit of South Yemen, but the

Britannia,

which had been originally commissioned as a hospital ship in 1948, was given clearance to enter the port and begin evacuation procedures.

I was informed by the ship's captain that nearly 4,000 evacuees were gathered on the beach, waiting to be spirited away by ships of different nations to the former French colony of Djibouti, 150 miles away. The first load of 350, primarily comprising diplomats and VIPs, was to be transported aboard the

Britannia

as soon as possible.

The remainder needed to be fed. On the beach. Immediately.

With no provisions made for cooking equipment, food stores, or fresh water on the beach, a few decisions had to be made, and quickly, by yours truly. There were undisguised elements of the story of the loaves and fishes in this challenge, and I took some of my cues from the similarities. First priority: to

decide on a limited menu that could be produced in large quantities. Second, to keep the preparations simple, but appealing. Third, to provide for the immediate nutritional requirements of those who would partake of the meal. Rice and pulses (beans) would be a marvelous, simple combination of carbohydrates and protein, much like bread and fish had been in Galilee. Lastly, to provide something to buoy the spirit. I knew right away that the menu would include a dessert. And I knew that something sweet to finish would help to provide vitality and energy.

I had taken a cursory inventory of the ship's stores, and soon landed upon a list of ingredients that fit the bill in every regard. My mates and I assembled a small mountain of sacks of rice, dried beans, flour, bags of frozen carrots and broccoli, plastic storage containers of fresh water, powdered milk, coffee, salt, pepper, butter, oil, sugar, sides of salt pork, and a spice mixture that I had dashed together for the beans, primarily composed of paprika, cayenne pepper, white pepper, brown sugar, coriander, cardamom, and cinnamon.

We ransacked the galleys for every last paper plate, plastic bowl, and cup, for plastic “sporks,” paper napkins, and sundries. The problem remained of supplying heating equipment and pots big enough to hold food for over three thousand people. Cooking in the galleys and transporting the food to the beach was out of the question. The

Britannia

was to begin evacuation right away, and none of our cooking equipment was portable.

In those moments, it helps to break your problem down to the absolute basics. Need very big pots. Metal. What's big, can hold lots of food, and is made of metal? Wait for itâ¦garbage cans. In the storeroom I found a complement of half a dozen fifty-gallon, pristine, aluminum garbage cans that had never been used. We hauled them on deck, then grabbed all of the Sterno and hexiblocks (which is a breakable, paraffin-based fuel) that we could carry, picked up shovels and some folding tables, and hit the beach.

We made our way to shore in a covered barge, which is a goodly sized motor launch, and anchored in the shallows. When we first arrived, we were relatively ignored. I disembarked and tried to get the lay of the land. The terrain seemed hospitable, and we were lucky in that we would be excavating in soft sand instead of hard clay. The sand would also be the perfect medium to hold in the heat from the fires we would have to build. A contingent of marines set up a secure perimeter on the dunes on the landward side, beyond which, only a few miles away, the conflict carried on unabated. The crosswinds were negligible, thankfully, so we hauled our supplies onto dry land. The offshore ships got all of the attention from those gathered on the beach just over a small rise, so I

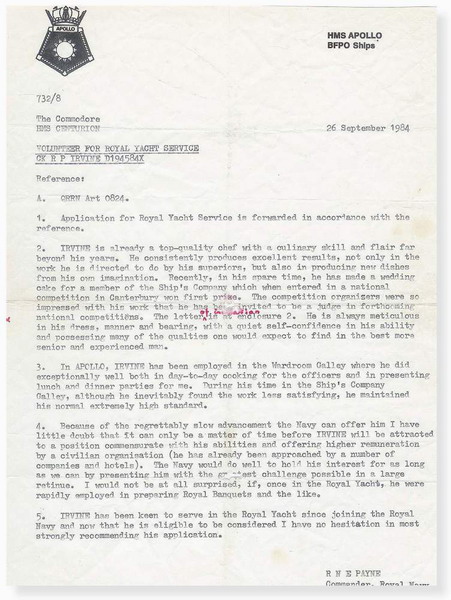

Letter of Recommendation for the

Britannia

went to work with my detail, digging pits in the sand, building fires in the bottom of each with Sterno and driftwood, and sinking garbage cans filled with water into each, one by one.

Our work came to a complete standstill for a brief, stirring moment as the

Britannia

pulled away with the first of its human cargo. The Royal Marine Band, which was always stationed aboard, played “Rule, Britannia!” from the

foredeck, with all of the ceremonial flourishes, then, “Land of Hope and Glory” as it faded from view. That music was a promise of rescue and return to home, and it is still difficult for me to recall without the hairs standing up on the back of my neck.

I soaked the beans for about twenty minutes instead of the recommended twenty-four hours, then built up the fire and basically cooked the living daylights out of them until they became tender, about two and a half hours later. I skimmed them and added the spice mixture, then divided the rice and cooked it in two of the cans. If you ever find the need to cook rice in a garbage can, bear in mind that it's incredibly heavy and thus difficult to stir, so don't get carried away and try to do it in one big batch.

We needed a colander, so we stretched some cheesecloth across two two-by-fours, managed to drain the rice, then combined the rice and the beans together. I cut strips of the salt pork and steamed them to doneness on top of the rice and bean mixture. In the fourth can, I brought the heat up to a rolling boil for cooking the broccoli and carrots.

Dessert was contrived in the last can, where with the powdered milk, sugar, and rice, I created the biggest bowl of rice pudding known to man.

Over the hill they came, first in smaller groups, then larger, but with great order and dignity. By later reckoning, I found out that we were about to feed more than three thousand of them on our beach that day, all told. They were Russian, British, German, Chinese, French, Jordanian, Filipino, Somali, Egyptian, and Sikh; short and tall, male and female, black, white, and brown, from the elderly to very small children. Some were quiet, some crying, some nervous, others patient and resigned. All of us to one degree or another were afraid, because the explosive sound of shelling and the sight of smoke never ceased in the background. Once we began service, I hardly looked up from ladling food into bowls for hours. It must have been good, because we served every scrap of food we cooked. In the end, the

Britannia

alone rescued 1,082 foreigners before we resumed our voyage to New Zealand and kept our appointment with the Queen.

Everyone who was hungry that day was well fed.

MAKES ABOUT 4 SERVINGS

8 pounds pork ribs (baby backs are great; you can also use beef ribs)

FOR THE RUB

¼ cup brown sugar

2 teaspoons salt

1

/

8

cup paprika

1

/

8

cup red chili powder

1

/

8

cup semicoarse black pepper

1 teaspoon garlic powder

1 teaspoon onion powder

FOR THE SAUCE

100 mL Jack Daniel's whiskey (half of a “flask-sized” bottle

or

two “airplane-sized” bottles)

1 tablespoon minced garlic (1 large clove)

½ cup Worcestershire sauce

½ cup apple juice

¼ cup tomato juice

1 tablespoon hot sauce (more if you like it spicy)

1 cup ketchup

1 tablespoon paprika

2 teaspoons black pepper

1 tablespoon onion powder

2 teaspoons salt

¼ cup corn syrup (light or dark)

I have often thought, if I'd met one of the people who had been stranded that day on the beach in Yemen, and they had a sudden craving for pork, rice, and beans, here's how I might make them today.

This is the most fantastic recipe for cooking pork ribs that I know. Now, I tightly wrap my ribs and cook them in plastic wrap, and people look at me like I'm crazy, but this method does an incredible job of locking in the juices and natural flavor of the ribs. This recipe makes enough rub and sauce for 8 pounds of ribs. For less just halve the recipe or save the extra for another time!

Wash

the ribs to remove any excess liquid and smells, and dry with paper towels.

Combine all the rub ingredients in a large mixing bowl and toss together until well mixed. Season the ribs liberally with the rub, preferably about 2 hours before cooking. Then wrap the entire section of meat in plastic wrap, making sure you cover it well, as the cooking method being used is actually steaming.

Leave the meat at room temperature until you place it in the oven, but for no longer than a couple of hours. (The rub will actually begin to “cure” the meat, acting as a preservative.)

Place the covered ribs into a 200 to 250-degree oven in a baking pan (the bottom part of a broiling pan is great because it is large and heavy duty). Cook for about 2 hours, the slower the better. (Don't have the oven any hotter than 250 degrees because the plastic wrap will melt.)

Whilst the ribs are cooking, begin making the sauce.

To

make the sauce, combine the Jack Daniel's and the minced garlic in a large pot and simmer until the Jack Daniel's is reduced by half.