Mom (15 page)

Authors: Dave Isay

My mother and father did not want their friends to know I was pregnant, and I’ve only found out recently how few of them did know. One of my mother’s best friends had no idea. I think what they really find incredible is that my mother didn’t confide in them. I think it was just a tremendous disappointment to my parents, and they didn’t want to tell people that I’d messed up or maybe that they’d messed up.

My parents had met Skip, and they liked him. I thought,

Well, I’m going to have to get married

. It didn’t happen. His parents did not know about our relationship, and they would not have liked him going out with a girl who wasn’t Jewish. So his brother-in-law got me a place in the Florence Crittenton Home for unwed mothers in a suburb of Boston.

Well, I’m going to have to get married

. It didn’t happen. His parents did not know about our relationship, and they would not have liked him going out with a girl who wasn’t Jewish. So his brother-in-law got me a place in the Florence Crittenton Home for unwed mothers in a suburb of Boston.

It was a pleasant place to be. We ate together in a dining room; we all took turns at different tasks in the kitchen and in cleaning. It was like an initiation—you’d meet other people in the same situation as you, get to know them, and find out how many people are just like you. We knitted baby clothes and read baby magazines. I made a bunny, a pink bunny, which—

Dave Mills:

I still have to this day.

I still have to this day.

Hilory:

And you didn’t know until recently that I had made it for you—the fact that you kept it all this time without that knowledge!

And you didn’t know until recently that I had made it for you—the fact that you kept it all this time without that knowledge!

I went into labor the day before or the day after you were due. I remember one girl who delivered about the same time I did—she did not want to see her baby. She said, “I’m glad it’s out of me! I want to be away from here and go on with my life!” She was angry with herself, she was angry with everybody, and she was angry with the baby. In my case, I said, “I want to feed my baby.” So they would bring you in during the day. At night, they said, “You’re going to need your sleep,” but during the day, every two hours, they’d bring you to me. And I

savored

it. I was there for a couple of weeks—they used to keep you in the hospital for a while.

savored

it. I was there for a couple of weeks—they used to keep you in the hospital for a while.

My social worker was very upset. “You said you didn’t want to see the baby beforehand. What’s changed?” I said, “I delivered him, and now I want to see him. I’ve changed my mind.” I actually thought, “I’m going to keep him somehow—I just can’t imagine giving a child away.”

Dave:

You told me that you left the hospital with me, which is not normally done.

You told me that you left the hospital with me, which is not normally done.

Hilory:

My mother came up to Massachusetts, picked us up, and drove us back to Connecticut.You were handed off to a social worker at a stop on the Merritt Parkway, with your pink bunny and your layette. My mother was split and torn. If it wasn’t for my father, you would probably have been with us, but my dad was the one who didn’t even want to see your picture. I know it was difficult for him, but this was the decision he had made.

My mother came up to Massachusetts, picked us up, and drove us back to Connecticut.You were handed off to a social worker at a stop on the Merritt Parkway, with your pink bunny and your layette. My mother was split and torn. If it wasn’t for my father, you would probably have been with us, but my dad was the one who didn’t even want to see your picture. I know it was difficult for him, but this was the decision he had made.

I thought of you every birthday and more often than that. It’s funny, because I used to think,

I wonder if he’s wondering today about the person that didn’t want him.

I always worried,

I hope he doesn’t think that I didn’t love him.

I was hoping you would look for me. I was hoping, but I also thought if a person grows up happy with a family, I don’t know if he would look for someone who gave him away.

I wonder if he’s wondering today about the person that didn’t want him.

I always worried,

I hope he doesn’t think that I didn’t love him.

I was hoping you would look for me. I was hoping, but I also thought if a person grows up happy with a family, I don’t know if he would look for someone who gave him away.

I made the decision when I turned sixty that I was going to do a search—I needed to know before I died what happened to this child.

Dave:

When I was a child growing up in a family with siblings that were all adopted, the fact that I was adopted was explained to me as early as I could understand it. I thought everybody was adopted—I thought that when parents have kids, they go to a building and pick them up. I can still remember, I was probably six or seven years old, and my friend was telling me how his mom was going to have a baby. My response was, “You mean she’s going to keep him?” I thought that everybody just ended up going to somebody else’s family.

When I was a child growing up in a family with siblings that were all adopted, the fact that I was adopted was explained to me as early as I could understand it. I thought everybody was adopted—I thought that when parents have kids, they go to a building and pick them up. I can still remember, I was probably six or seven years old, and my friend was telling me how his mom was going to have a baby. My response was, “You mean she’s going to keep him?” I thought that everybody just ended up going to somebody else’s family.

Hilory:

Isn’t that a great thing to think that you’re there by someone’s choice—someone wanted a child so much that there you are—

I want you, you’re mine

.

Isn’t that a great thing to think that you’re there by someone’s choice—someone wanted a child so much that there you are—

I want you, you’re mine

.

Dave:

At least consciously, I never felt rejection over it. The reason I made the first steps to look for you was mostly curiosity. It wasn’t something I was preoccupied with or stayed awake at night losing sleep over, but I just had this curiosity.

At least consciously, I never felt rejection over it. The reason I made the first steps to look for you was mostly curiosity. It wasn’t something I was preoccupied with or stayed awake at night losing sleep over, but I just had this curiosity.

I’d been living in Ontario almost half a year. This letter came in the mail that had been forwarded from my last address. It came originally from Northport, New York. Pardon the expression, but I thought to myself,

Who the hell do I know in New York?

Which was nobody. I opened that envelope and read the first few lines, and my chin hit my lap. I never had a moment in my life where I was so stunned, where I physically couldn’t read beyond that. This might sound melodramatic, but it changed my life.

Who the hell do I know in New York?

Which was nobody. I opened that envelope and read the first few lines, and my chin hit my lap. I never had a moment in my life where I was so stunned, where I physically couldn’t read beyond that. This might sound melodramatic, but it changed my life.

Hilory:

I had written that letter so long ago and it had been returned twice. The lady at the agency hadn’t been able to find you, so we thought,

Well, that’s that.

I had written that letter so long ago and it had been returned twice. The lady at the agency hadn’t been able to find you, so we thought,

Well, that’s that.

Then you left me a voice mail message, and I was like,

Oh my God, I have to sit down!

It was just amazing when I called you and you answered! It was just like,

Hello, where have you been all my life

? Like we just picked up where we left off.

Oh my God, I have to sit down!

It was just amazing when I called you and you answered! It was just like,

Hello, where have you been all my life

? Like we just picked up where we left off.

Dave:

If you could have said anything to me as a five-year-old child, what would you have said?

If you could have said anything to me as a five-year-old child, what would you have said?

Hilory:

I would have said, “I hope that you’re very happy. I hope your dad is good to you, and I hope your mom is a lady you love very much. I hope she’s making chocolate chip cookies for you and playing in the snow with you. I hope she bakes you a cake on your birthday, and you blow out candles and sing!” Because that’s what I was hoping would happen for you. And in fact, I think that’s how it was.

I would have said, “I hope that you’re very happy. I hope your dad is good to you, and I hope your mom is a lady you love very much. I hope she’s making chocolate chip cookies for you and playing in the snow with you. I hope she bakes you a cake on your birthday, and you blow out candles and sing!” Because that’s what I was hoping would happen for you. And in fact, I think that’s how it was.

Recorded in New York, New York, on August 15, 2007.

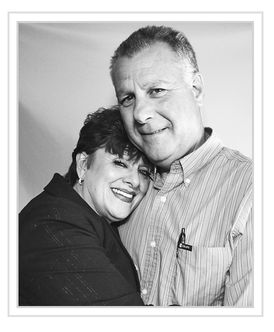

MYRA DEAN, 61

talks to her boyfriend,

GARY JAMISON, 58

talks to her boyfriend,

GARY JAMISON, 58

Myra Dean:

My son was Richard Damon Stark. People used to ask him what he wanted to be when he grew up, and he used to tell people he wanted to be a marine biologist or a garbage man. He wanted to be ten. He didn’t make it. He was nine years and four months old when he died.

My son was Richard Damon Stark. People used to ask him what he wanted to be when he grew up, and he used to tell people he wanted to be a marine biologist or a garbage man. He wanted to be ten. He didn’t make it. He was nine years and four months old when he died.

He and I had moved to a little house in Kansas City after I separated from his dad. I bought it because when I was looking at apartments, Rich kept getting more and more upset. I said, “Rich, why are you so upset?” He just kept saying, “Momma, I don’t want to move to an apartment, I don’t want to move to an apartment.” And I said, “Why?” Finally he said it was because his little friend told him his mom got a divorce and they moved to an apartment and she got mean. So I took every apartment off the list and I thought,

I will find a house I can afford to buy

.

I will find a house I can afford to buy

.

I found this little house, and it was perfect. Three weeks to the day after we moved in was May 13, 1977 and I was going to go out with my girlfriend. Rich had a new friend named Steve, and they were riding bikes. When I went to get the babysitter, I went down the street and said, “Come on, we’ve got to go.” And he didn’t want to go; he just wanted to stay and ride bikes with Steve. I thought to myself,

I don’t want to tie him to his momma’s apron strings

. Steve’s mom was standing there, and she said, “We’re going to go ride bikes. Just leave him here with me.” I didn’t have far to go, and so I said, “Watch for cars.” And I left. When I came back, I pulled up in front of the little house, and I saw this crowd of people at the end of the street and ambulance lights.

I don’t want to tie him to his momma’s apron strings

. Steve’s mom was standing there, and she said, “We’re going to go ride bikes. Just leave him here with me.” I didn’t have far to go, and so I said, “Watch for cars.” And I left. When I came back, I pulled up in front of the little house, and I saw this crowd of people at the end of the street and ambulance lights.

I got out of the car, and I knew the minute I opened the car door and put my feet on the ground that it was Rich. I guess some people don’t believe that you can know that, but I knew. I got out of the car and I just started running, and when I got there, there were people all around him. They wouldn’t let me up to him. They were working on him, and they just sat me down. I had an out-of-body experience: I went up in the air, and I looked down, and I could see me sitting on the ground. I could see them working on Rich. They put him in the back of the ambulance, and they put me in a police car and we followed the ambulance. I just started screaming. I can still remember the face on the policeman—I think it about killed him. I remember him turning to me and saying, “Ma’am, I’ve got kids, too.” I kept saying, “Even if my family comes, don’t leave me, don’t leave me!” And he didn’t—he stayed right there with me. My ex-husband came. They took us in a hallway, and they just said, “There was nothing we could do. He’s gone.” I can remember having my back to the wall, and I just slid down, leaning against that wall.

Later I found out that a guy had been hot-rodding through our neighborhood. The car went airborne and over a six-foot hedge, and it landed on Rich and Steve. The car flipped over. Steve was caught where the hood and the windshield made like a little tent, but the car landed on Rich. They had pulled the driver out, and he kept saying, “Oh my God, what have I done? What have I done?” Steve’s mom was a nurse, and even with her own son lying there, she tried to give Rich CPR.

The ambulance driver came to me at the hospital, and he said, “Ma’am, I’m not supposed to tell you this—but he was dead at the scene.” He’ll never know what that meant to me, because one of the things that was the hardest for me was,

What if he was suffering and I wasn’t there for him?

What if he was suffering and I wasn’t there for him?

Steve’s mother said the last thing that he said to her was, “My momma told me to watch for cars.” He wasn’t even in the street—they’d gone up into the yard. Steve’s mom walked in the garage to get her bike to take them riding, and Richie wanted to go to that yard and sit and watch the sunset. So it’s a bittersweet thing that he died watching the sunset.

I always try to find ways to explain to people about the pain: It’s as if you’ve had an invisible amputation, you know? When you lose your child it’s like somebody has just amputated a huge chunk of your heart. The difference is people can’t see the amputation.

When Rich died, I thought I wouldn’t live ten minutes. I was astonished when I’d lived ten days and mortified when I’d lived ten months, and not even grateful yet when I had lived ten years. I was mostly surprised; there was no one more astonished that I’d survived it than myself. God, in his mercy, does not give you all of the impact at one time.You’re just so numb for so long, and then it starts to seep in. After a year or two people think you should be getting better, but that’s really when the shock is wearing off and you start to feel again. And oh my God, it’s

so bad

. But fortunately, I found other people who had been through it, and they said, “It won’t be like this forever,” and it hasn’t been.

so bad

. But fortunately, I found other people who had been through it, and they said, “It won’t be like this forever,” and it hasn’t been.

I needed to be with other people that knew what was happening to me. I’d meet with other bereaved parents, and we’d talk about how you’d be at the grocery store with your cart, you’d come around the corner, and somebody at the other end would look up and see you, and you could see it on their faces—it was like they had rockets on the carts—they would just go and hit the next aisle. People would avoid even passing you in the grocery store, because God forbid they should say, “How are you doing?” and upset you. Seriously, people think after you lose a child if they don’t mention it maybe you won’t think about it. It’s just insane.

I miss Rich terribly and I wonder what he would be like. He was just a happy kid, and he died watching the sunset. I used to have such terrible guilt about that, because I always used to think if I hadn’t taught him to see everything that was around him, then he would have just been off riding his bike like a normal kid. He wouldn’t have gone down to watch the sunset, and if he hadn’t been in that yard, he wouldn’t have been killed. You always think you can protect your children and you can’t—it’s such a feeling of helplessness and powerlessness.

Today I’m in a far better place—as they say, a far, far better place. In the story of Job, Job lost everything, and he got everything back twofold. With me, I have two great stepchildren that I raised: Mike and Sara. I’m their mom. I didn’t have them, but they’re mine. I’m blessed and I’m loved, and I know that I’ve made a difference. If I was buried, I’d want my tombstone to say, “She made a difference.” That’s really the only thing that matters in this world.

Recorded in Abilene, Texas, on March 21, 2008.

Other books

Oracle by Alex Van Tol

Stand-In Wife by Karina Bliss

What Distant Deeps by David Drake

Tasting Fear by Shannon McKenna

The Secret Diamond Sisters by Michelle Madow

The Tankermen by Margo Lanagan

Shooting for the Stars by Sarina Bowen

Haunting of Lily Frost by Weetman, Nova

In the Orient by Art Collins

Kaleidoscope by Dorothy Gilman