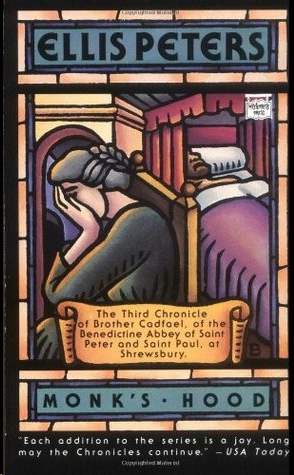

Monk's Hood

Authors: Ellis Peters

Monk’s

Hood

The

Third Chronicle of Brother Cadfael, of the Benedictine Abbey of Saint Peter and

Saint Paul, at Shrewsbury

Ellis Peters

ON

THIS PARTICULAR MORNING at the beginning of December, in the year 1138, Brother

Cadfael came to chapter in tranquillity of mind, prepared to be tolerant even

towards the dull, pedestrian reading of Brother Francis, and long-winded legal

haverings of Brother Benedict the sacristan. Men were variable, fallible, and to

be humoured. And the year, so stormy in its earlier months, convulsed with

siege and slaughter and disruptions, bade fair to end in calm and comparative

plenty. The tide of civil war between King Stephen and the partisans of the

Empress Maud had receded into the south-western borders, leaving Shrewsbury to

recover cautiously from having backed the weaker side and paid a bloody price

for it. And for all the hindrances to good husbandry, after a splendid summer

the harvest had been successfully gathered in, the barns were full, the mills

were busy, sheep and cattle thrived on pastures still green and lush, and the

weather continued surprisingly mild, with only a hint of frost in the early

mornings. No one was wilting with cold yet, no one yet was going hungry. It

could not last much longer, but every day counted as blessing.

And

in his own small kingdom the crop had been rich and varied, the eaves of his

workshop in the garden were hung everywhere with linen bags of dried herbs, his

jars of wine sat in plump, complacent rows, the shelves were thronging

with bottles and pots of specifics for all the ills of winter, from

snuffling colds to seized-up joints and sore and wheezing chests. It was a

better world than it had looked in the spring, and an ending that improves on

its beginning is always good news.

So

Brother Cadfael rolled contentedly to his chosen seat in the chapter-house,

conveniently retired behind one of the pillars in a dim corner, and watched

with half-sleepy benevolence as his brothers of the house filed in and took

their places: Abbot Heribert, old and gentle and anxious, sadly worn by the

troublous year now near its ending; Prior Robert Pennant, immensely tall and

patrician, ivory of face and silver of hair and brows, ever erect and stately,

as if he already balanced the mitre for which he yearned. He was neither old

nor frail, but an ageless and wiry fifty-one, though he contrived to look every

inch a patriarch sanctified by a lifetime of holiness; he had looked much the

same ten years ago, and would almost certainly change not at all in the twenty

years to come. Faithful at his heels slid Brother Jerome, his clerk, reflecting

Robert’s pleasure or displeasure like a small, warped mirror. After them came

all the other officers, sub-prior, sacristan, hospitaller, almoner, infirmarer,

the custodian of the altar of St. Mary, the cellarer, the precentor, and the

master of the novices. Decorously they composed themselves for what bade fair

to be an unremarkable day’s business.

Young

Brother Francis, who was afflicted with a nasal snuffle and somewhat sparse

Latin, made heavy weather of reading out the list of saints and martyrs to be

commemorated in prayer during the coming days, and fumbled a pious commentary

on the ministry of St. Andrew the Apostle, whose day was just past. Brother

Benedict the sacristan contrived to make it sound only fair that he, as

responsible for the upkeep of church and enclave, should have the major claim

on a sum willed jointly for that purpose and to provide lights for the altar of

the Lady Chapel, which was Brother Maurice’s province. The precentor

acknowledged the gift of a new setting for the “Sanctus,” donated by the

composer’s patron, but by the dubious enthusiasm with which he welcomed so

generous

a gift, he did not think highly of its merits, and it

was unlikely to be heard often. Brother Paul, master of the novices, had a

complaint against one of his pupils, suspected of levity beyond what was

permitted to youth and inexperience, in that the youngster had been heard singing

in the cloisters, while he was employed in copying a prayer of St. Augustine, a

secular song of scandalous import, purporting to be the lament of a Christian

pilgrim imprisoned by the Saracens, and comforting himself by hugging to his

breast the chemise given him at parting by his lover.

Brother

Cadfael’s mind jerked him back from incipient slumber to recognise and remember

the song, beautiful and poignant. He had been in that Crusade, he knew the

land, the Saracens, the haunting light and darkness of such a prison and such a

pain. He saw Brother Jerome devoutly close his eyes and suffer convulsions of

distress at the mention of a woman’s most intimate garment. Perhaps because he

had never been near enough to it to touch, thought Cadfael, still disposed to

be charitable. Consternation quivered through several of the old, innocent,

lifelong brothers, to whom half the creation was a closed and forbidden book.

Cadfael made an effort, unaccustomed at chapter, and asked mildly what defence

the youth had made.

“He

said,” Brother Paul replied fairly, “that he learned the song from his

grandfather, who fought for the Cross at the taking of Jerusalem, and he found

the tune so beautiful that it seemed to him holy. For the pilgrim who sang was

not a monastic or a soldier, but a humble person who made the long journey out

of love.”

“A

proper and sanctified love,” pointed out Brother Cadfael, using words not

entirely natural to him, for he thought of love as a self-sanctifying force,

needing no apology. “And is there anything in the words of that song to suggest

that the woman he left behind was not his wife? I remember none. And the music

is worthy of noting. It is not, surely, the purpose of our order to obliterate

or censure the sacrament of marriage, for those who have not a celibate

vocation. I think this young man may have done nothing very wrong. Should

not Brother Precentor try if he has not a gifted voice? Those

who sing at their work commonly have some need to use a God-given talent.”

The

precentor, startled and prompted, and none too lavishly provided with singers

to be moulded, obligingly opined that he would be interested to hear the novice

sing. Prior Robert knotted his austere brows, and frowned down his patrician

nose; if it had rested with him, the errant youth would have been awarded a

hard penance. But the master of novices was no great enthusiast for the lavish

use of the discipline, and seemed content to have a good construction put on

his pupil’s lapse.

“It

is true that he has shown as earnest and willing, Father Abbot, and has been

with us but a short time. It is easy to forget oneself at moments of

concentration, and his copying is careful and devoted.”

The

singer got away with a light penance that would not keep him on his knees long

enough to rise from them stiffly. Abbot Heribert was always inclined to be

lenient, and this morning he appeared more than usually preoccupied and

distracted. They were drawing near the end of the day’s affairs. The abbot rose

as if to put an end to the chapter.

“There

are here a few documents to be sealed,” said Brother Matthew the cellarer,

rustling parchments in haste, for it seemed to him that the abbot had turned

absent-minded, and lost sight of this duty. “There is the matter of the

fee-farm of Hales, and the grant made by Walter Aylwin, and also the guestship

agreement with Gervase Bonel and his wife, to whom we are allotting the first

house beyond the mill-pond. Master Bonel wishes to move in as soon as may be,

before the Christmas feast…”

“Yes,

yes, I have not forgotten.” Abbot Heribert looked small, dignified but

resigned, standing before them with a scroll of his own gripped in both hands.

“There is something I have to announce to you all. These necessary documents

cannot be sealed today, for sufficient reason. It may well be that they are now

beyond my competence, and I no longer have the right to conclude any agreement

for this community.

I have here an instruction which was

delivered to me yesterday, from Westminster, from the king’s court. You all

know that Pope Innocent has acknowledged King Stephen’s claim to the throne of

this realm, and in his support has sent over a legate with full powers,

Alberic, cardinal-bishop of Ostia. The cardinal proposes to hold a legatine

council in London for the reform of the church, and I am summoned to attend, to

account for my stewardship as abbot of this convent. The terms make clear,”

said Heribert, firmly and sadly, “that my tenure is at the disposal of the

legate. We have lived through a troubled year, and been tossed between two

claimants to the throne of our land. It is not a secret, and I acknowledge it,

that his Grace, when he was here in the summer, held me in no great favour,

since in the confusion of the times I did not see my way clear, and was slow to

accept his sovereignty. Therefore I now regard my abbacy as suspended, until or

unless the legatine council confirms me in office. I cannot ratify any

documents or agreements in the name of our house. Whatever is now uncompleted

must remain uncompleted until a firm appointment has been made. I cannot

trespass on what may well be another’s field.”

He

had said what he had to say. He resumed his seat and folded his hands

patiently, while their bewildered, dismayed murmurings gradually congealed and

mounted into a boiling, bees’-hive hum of consternation. Though not everyone

was horrified, as Cadfael plainly saw. Prior Robert, just as startled as the

rest, and adept at maintaining a decorous front, none the less glowed brightly

behind his ivory face, drawing the obvious conclusion, and Brother Jerome,

quick to interpret any message from that quarter, hugged himself with glee

inside the sleeves of his habit, while his face exhibited pious sympathy and

pain. Not that they had anything against Heribert, except that he continued to

hold an office on which impatient subordinates were casting covetous eyes. A

nice old man, of course, but out of date, and far too lax. Like a king who

lives too long, and positively invites assassination. But the rest of them fluttered

and panicked like hens invaded by the fox, clamouring variously:

“But,

Father Abbot, surely the king will restore you!”

“Oh,

Father, must you go to this council?”

“We

shall be left like sheep without a shepherd!”

Prior

Robert, who considered himself ideally equipped to deal with the flock of St.

Peter himself, if need be, gave that complaint a brief, basilisk glare, but

refrained from protest, indeed murmured his own commiseration and dismay.

“My

duty and my vows are to the Church,” said Abbot Heribert sadly, “and I am bound

to obey the summons, as a loyal son. If it pleases the Church to confirm me in

office, I shall return to take up my customary ward here. If another is

appointed in my place, I shall still return among you, if I am permitted, and

live out my life as a faithful brother of this house, under our new superior.”

Cadfael

thought he caught a brief, complacent flicker of a smile that passed over

Robert’s face at that. It would not greatly disconcert him to have his old

superior a humble brother under his rule at last.

“But

clearly,” went on Abbot Heribert with humility, “I can no longer claim rights

as abbot until the matter is settled, and these agreements must rest in

abeyance until my return, or until another considers and pronounces on them. Is

any one of them urgent?”

Brother

Matthew shuffled his parchments and pondered, still shaken by the suddenness of

the news. “There is no reason to hurry in the matter of the Aylwin grant, he is

an old friend to our order, his offer will certainly remain open as long as

need be. And the Hales fee-farm will date only from Lady Day of next year, so

there’s time enough. But Master Bonel relies on the charter being sealed very

soon. He is waiting to move his belongings into the house.”