Moses and Akhenaten (17 page)

Read Moses and Akhenaten Online

Authors: Ahmed Osman

The amount of construction work in which he was involved is another indication of a substantial reign. Only Pharaohs who ruled for a considerable time â Tuthmosis III, Amenhotep III and Ramses II, for example â were able to leave great buildings. Seti I completed a funerary temple that had been started by his father, Ramses I, at Kurnah in Western Thebes. Although the pylon of the temple, which he dedicated to the cult of himself and his father, is no longer to be found, the façade, with lotus-bud columns, is still in perfect shape, together with a number of the chambers in front of the sanctuary. The decoration is very carefully executed.

At Abydos, the centre of worship of Osiris, god of the dead, Seti built a great and beautiful temple which Maspero describes in the following terms: âThe building material mainly employed here was the white limestone of Turah, but of a most beautiful quality, which lent itself to the execution of bas-reliefs of great delicacy, perhaps the finest in Ancient Egypt ⦠When the decoration of the temple was complete, Seti regarded the building as too small for its divine inmate, and accordingly added to it a new wing, which he built along the whole length of the southern wall; but he was unable to finish it completely .. .'

5

Another great architectural work, started by Seti and completed by his son, Ramses II, is the Hypostyle Hall at Karnak, described by Maspero as âthis almost superhuman undertaking': âThe hall measures 162 feet in length, by 325 in breadth. A row of 12 columns, the largest ever placed inside a building, runs up the centre, having capitals in the form of inverted bells. One hundred and twenty-two columns with lotus-form capitals fill the aisles, in rows of nine each. The roof of the central bay is 74 feet above the ground, and the cornice of the two towers rises 63 feet higher ⦠The size is immense, and we realise its immensity more fully as we search our memory in vain to find anything with which to compare it.'

6

All of this great building work must have required a great deal of time in planning, the cutting and transportation of stone, and painting and decorating to a perfect finish, certainly longer than eleven years, particularly when Seti I was engaged in his many wars during the early part of his reign.

A further pointer to a substantial reign is the fact that evidence from the south shows that, while Seti ruled Egypt, there were two viceroys for Kush, Amenemopet, son of Paser I, and Yuni.

7

This is unlikely to have been the case had Seti ruled for only eleven years.

If the arguments in favour of a reign of twenty-nine years for Seti I are accepted, this would mean that he was born in Year 2 of his father, which seems possible from the above evidence.

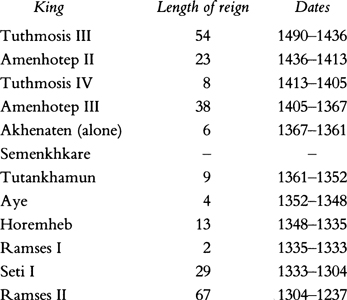

We are now in a position to construct a chronology for the period that concerns us:

On the basis of this chronology of Egyptian history and the chronology of the Sojourn set out in an earlier chapter, we can make the following deductions:

⢠Akhenaten was born in Year 11 or 12 of his father, 1394

BC;

⢠Akhenaten fell from power and fled to Sinai in 1361

BC

at the age of thirty-four or thirty-five;

⢠If Akhenaten was Moses, he was around sixty when he returned to Egypt and led the Exodus in the reign of Ramses I.

Whether or not Akhenaten lost his life at the time he fell from power, which has been widely assumed, will be argued in a later chapter.

11

THE BIRTHPLACE OF AKHENATEN

I

F

Moses and Akhenaten are the same person, they must have been born at the same place at the same time.

From Old Testament and Egyptian sources we have mention of six Eastern Delta cities:

â¢Â Â

Avaris,

the old Hyksos capital, dating from more than two centuries earlier;

â¢Â Â

Zarw-kha,

the city of Queen Tiye, mentioned in the pleasure-lake scarab of Year 11 of her husband, Amenhotep III

;

â¢Â Â

Zarw

or

Zalw (Sile

of the Greeks), the frontier fortified city, mentioned in texts starting from the Eighteenth Dynasty, whose precise whereabouts in the fourteenth nome is known;

â¢Â Â

Pi-Ramses,

the Eastern Delta residence of Pharaohs of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties, known as âHouse of Ramses, Beloved of Amun, Great of Victories';

â¢Â Â

Raamses,

the city built by the Israelites' forced labour;

â¢Â Â

Rameses

(the same place as Raamses), where the Exodus began.

There is now general agreement among scholars that Pi-Ramses was situated on the site of the former Hyksos capital, Avaris, and that it was the same city as Raamses, the city built by the Israelites' harsh labour, and Rameses, named in the Old Testament as the starting point of the Exodus. The two questions at issue, therefore, are: are Pi-Ramses/Avaris to be found in the same location as Zarw? Was Zarw also Tiye's city, Zarw-kha? The answers to these questions are critical because of what we know of the birth of Moses and Akhenaten.

On their arrival in Egypt the Israelites settled at Goshen in the Eastern Delta, near to the known position of Zarw. As there is no evidence that they ever migrated to another part of the country, this must have been the area that provides the background for the Book of Exodus account of the birth of Moses. It is also implicit in the story that the ruling Pharaoh of the time had a residence nearby: he was in a position to give orders in person to the midwives to kill the child born to the Israelite woman if it proved to be a boy, and, according to the Book of Exodus, the sister of Moses was able to watch what happened when âthe daughter of Pharaoh came down to wash herself at the river' and noticed the basket containing Moses hidden among the reeds on the bank of the Nile. Later, when Moses and his brother Aaron had a series of meetings with Pharaoh there is no indication that they had to travel any distance for these meetings to take place.

In the case of Akhenaten, the pleasure lake scarab, dated to Year 11 (1394

BC

) of his father, Amenhotep III, plus other evidence, points to his birth having taken place at Zarw-kha. Six versions have been found of the scarab, issued to commemorate the creation of a pleasure lake for the king's Great Royal Wife, Tiye. Although there are some minor differences, they all agree on the main points of the text, which runs as follows:

Year 11, third month of Inundation (first season), day 1, under the majesty of Horus⦠mighty of valour, who smites the Asiatics, King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Neb-Maat-Re, Son of Re Amenhotep Ruler of Thebes, who is given life, and the Great Royal Wife Tiye, who liveth. His Majesty commanded the making of a lake for the Great King's Wife Tiye, who liveth, in her city of Zarw-kha. Its length 3700 cubits, its breadth 700 cubits. [One of the scarabs, a copy of which is kept at the Vatican, gives the breadth as 600 cubits, and also mentions the names of the queen's parents, Yuya and Tuya, indicating that they were still alive at the time.] His Majesty celebrated the feast of the opening of the lake in the third month of the first season, day 16, when His Majesty sailed thereon in the royal barge

Aten Gleams.

1

In my previous book

2

I argued that Pi-Ramses, Avaris and Zarw-kha were all to be found at one location â the frontier fortified city of Zarw, to the east of modern Kantarah, which is to the south of Port Said on the Suez Canal. To recapitulate what I believe to have been the correct sequence of events â¦

Here the kings of the Twelfth Dynasty are known to have built a fortified city (20th century

BC

.) The autobiography of Sinuhi, a court official who fled from Egypt to Palestine during the last days of Amenemhat I, the first king of the Twelfth Dynasty (1970

BC),

mentions his passing the border fortress, which at that time bore the name âWays of Horus'. The border city was rebuilt and refortified by the Asiatic Hyksos rulers who took control of Egypt for just over a century from the mid-seventeenth century

BC.

During this period it became known as Avaris. Later, when the kings of the Eighteenth Dynasty expelled the Hyksos, they in turn rebuilt the city with new fortifications, it was given the new name of Zarw and it became the main outpost on the Asiatic frontier, the point at which Egyptian armies began and ended their campaigns against Palestine/Syria.

During the time of Tuthmosis IV (1413â1405

BC),

his queen had an estate and residence within Zarw. Subsequently, Amenhotep III, the son of Tuthmosis IV, gave this royal residence, Zarw-kha, within the walls of Zarw, to his wife, Queen Tiye, as a present. I explained this event as stemming from the king's desire to allow Tiye to have a summer residence in the area of nearby Goshen in the Eastern Delta where her father's Israelite family had been allowed to settle. (I regard Yuya, Queen Tiye's father, as being the Patriarch Joseph, of the coat of many colours, who brought the tribe of Israel from Canaan to dwell in Egypt.)

Later still, after the fall of the Amarna kings, who were descendants of both Amenhotep III and Yuya, Horemheb, the king who succeeded them, deprived the Israelites of their special position at Goshen and turned their city of Zarw into a prison. There he appointed Pa-Ramses and his son, Seti, as viziers and mayors of Zarw as well as commanders of the fortress and its troops. Pa-Ramses, the new mayor of the city, forced the Israelites into harsh labour, building for him what the Book of Exodus describes as a âstore city' within the walls of Zarw. Pa-Ramses followed Horemheb on the throne as Ramses I in 1335

BC,

establishing the Nineteenth Dynasty, and it was during his brief reign, lasting little more than a year, that Moses led the Israelites out of the Eastern Delta into Sinai.

At the time he came to the throne, Ramses I already had his residence at Zarw, being the city's mayor. His son, Seti I, and the latter's son, Ramses II, later established a new royal residence at Zarw that became known as Pi-Ramses and was used as the Delta capital of the Ramesside kings of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties for about two centuries. The kings of the Twenty-first Dynasty established a new residence at Tanis, south of Lake Menzalah, and made use in its construction of many monuments and much stone from Pi-Ramses, which misled later scribes into the erroneous belief that Pi-Ramses and Tanis were identical locations.

The whole issue of whether or not Pi-Ramses/Avaris and Zarw are to be found at the same location has been clouded by the fact that, while we know the precise location of Zarw, scholars have in the course of this century canvassed the claims of no fewer than six other sites in the Eastern Delta, in addition to Tanis, as the location of Pi-Ramses/Avaris, and two alternative sites â one at Thebes, the other in Middle Egypt â as the site of Tiye's city. The Delta sites have been advanced even if they failed to yield the required archaeological evidence, were in the wrong nome and, in some cases, did not exist at the relevant time. Each was abandoned in turn to be replaced by a seventh site, Qantir/Tell el-Dab'a. Investigations at Tell el-Dab'a, just over a mile south of Qantir (one of the sites suggested earlier, and now revived), were begun by the University of Vienna and the Austrian Archaeological Institute in 1966 and are still continuing.

This location has achieved considerable acceptance as the site of Pi-Ramses/Avaris since Manfred Bietak, the Austrian Egyptologist in charge of the excavations, gave an interim report on the expedition's findings in 1979. Yet this site, too, does not withstand close scrutiny any more than the previous six in the Eastern Delta that had been put forward. Recent archaeological discoveries in the Kantarah area make it unnecessary to argue at this point the objections to the Qantir/Tell el-Dab'a location, which can be found in Appendix D: instead I am concentrating here on some of the mass of evidence that Pi-Ramses/Avaris is to be found on the same site as Zarw. From written sources we know that:

â¢Â  Pi-Ramses was situated in a fertile wine-producing area and lay in the centre of a great vineyard: Zarw was in a wine-producing area, which is supported by two pieces of evidence. Remains of wine jars, sent from Zarw by its then mayor Djehutymes for celebrations of Amenhotep III's first jubilee in his Year 30, were found in the Malkata palace complex at Western Thebes,

3

and a wine jar from the house of Aten at Zarw, belonging to his Year 5, was found in the tomb of Tutankhamun;

â¢Â  Pi-Ramses was âthe forefront of every foreign land, the end of Egypt', located âbetween Palestine and Egypt':

4

Zarw had an identical location, at the starting point of the âroad of Horus', leading to Palestine;

â¢Â  Pi-Ramses could be reached by water from Memphis: Zarw could be reached by water from Memphis;

â¢Â  Pi-Ramses was connected by water with the fortress of Zarw and the Waters of Shi-hor (north and north-west of Zarw), which fits exactly what we know of the Ramesside Delta residence;