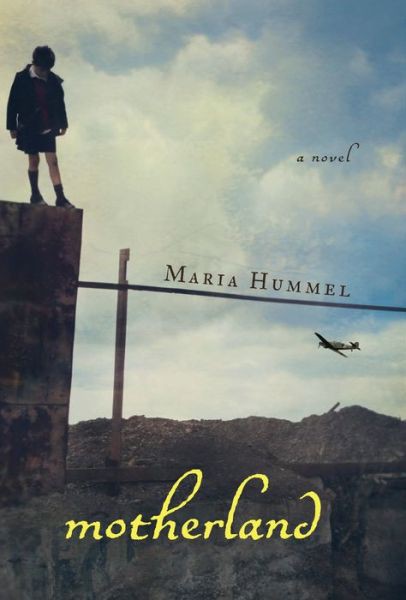

Motherland

motherland

mother land

Maria Hummel

COUNTER POINT

BERKELEY

Copyright © 2014 Maria Hummel

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hummel, Maria.

Motherland : A Novel / Maria Hummel.

1.

Families—Germany—Fiction. 2.

World War, 1939–1945—Germany—Fiction. 3.

Family secrets—Fiction. 4.

Historical fiction.

I. Title.

PS3608.U46M68 2014

813’.6—dc23

2013026157

ISBN 978-1-61902-354-3

Cover design by Ann Weinstock

Interior design by Neuwirth & Associates

C

OUNTERPOINT

1919 Fifth Street

Berkeley, CA 94710

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

For Manfred Karl Hummel

mutterland

Mein Vaterland ist tot sie haben es begraben im Feuer

Ich lebe in meinem Mutterland

—

Wort

—

Rose Ausländer

motherland

My Fatherland is dead They buried it in fire

I live in my Motherland—Word

—

translation by Eavan Boland

Contents

When Liesl heard the noise from the cellar, her hand shook and the coffee spilled. The liquid spread in claws across the counter, its color neither brown nor red nor black, but some combination of all three, earthen and old. A hopeless feeling rose in her chest. She had discovered the grounds deep in the pantry yesterday, tucked behind a post, in a tiny tin next to a tiny pot of jam, both labeled in the first wife’s hand. It was surely the last real coffee in all of Hannesburg, boiled with the last of the morning coal, the sharp selfish heaven of its scent rising toward her face. Then it splashed everywhere.

She heard the noise again, a grating, chinking sound, and then the murmur of the boys. What were they doing down there? Everything made her startle this morning. She had sent the package to Frank two weeks ago, confidently inking the address of the Weimar hospital where he was stationed as a reconstructive surgeon.

Nothing suspicious in here

, she hoped her bright, erect letters would imply. Yet she hadn’t heard back from him. Two weeks, and two more letters had passed. She told herself that with disrupted railway schedules and parcel searches, the package could take much longer to arrive. If the officials found what she’d hidden inside, if, if—she pressed her hands to her temples.

The baby stirred in the cradle by her feet. He refused to sleep in his crib by day, preferring the small portable nest of wood that moved from

room to room. He refused stillness, too. Whenever the house went too quiet or his cradle stopped swaying, he woke and cried.

She used her shin to shift the cradle side-to-side, side-to-side, as she tried to scoop the coffee back into her cup. She wanted it. She wanted it for herself, and because Susi must have wanted it once, to have gone through the effort of preserving such a miniscule portion. Then again, Susi had saved everything: thread too short to sew with, buttons to lost shirts, the heel of a shoe, the page of a missing book. In the kitchen, relics from the former cook still lingered, too: the hourglass, a cast-iron cauldron for cooking on a hearth. Because the former Frau Kappus had thrown out none of them, neither would her replacement. This made the rooms impossible to keep clean. There were so many objects and they each demanded the particular attention of a household used to servants, and not the friendless new mother of three boys.

Downstairs, a dull thud. Ani said something in his exuberant voice.

Liesl didn’t want to see what they were doing. She had potatoes to peel and Hans’s hems to let out and a quick trip to the butcher to make, all the while darting glances above the treetops for Allied planes. She had to finish knitting six pairs of socks for the Frauenschaft collection to send to soldiers in the Ardennes. She had to grit her teeth through the radio program that Hans liked switching on, that always started with the “Horst Wessel Song,” its notes marching through her head like a line of ants, eating up everything. She wasn’t sure what bothered her more—that motherhood was so much more unnerving than she’d expected, or that the Party’s speeches now sickened her. Every day, panic and mistrust pooled like black water in her gut.

She reached for her cup, then a soup pan, pouring the coffee back. It was silly to warm it again, but all morning she’d longed for one hot sip, almost burning. For the heat and the sour bitterness to fill her mouth. To taste the quiet, simple mornings before her marriage, when she’d

sat by the window of her room at the spa, lonely, but full of hope and purpose.

Another thud below. It sounded like meat falling. Liesl rushed for the stairs.

The boys stood before a crack in the cellar’s west wall, their faces silvered by weak window light. A giant chunk of wall lay on the floor. Hans stood closer to it. He looked much older than ten; in a few years he would have the height and shoulders of a man. His face resembled his father’s more than ever: the same craggy mouth and jaw, same blue eyes under a thunder of brows. In contrast, Ani’s features were still fluid and childlike, shifting with every thought. Right now, they rippled with surprise as the crack quivered and widened.

“What’s going on here?” Liesl demanded.

Neither of them answered. Hans had his arms down, his palms open and aimed back, as if he were shielding his brother from an attack. He winced when the crack split and a metal spade poked through, but Ani ran forward, saying, “Look, look!” The spade retreated. Pale worms shoved the grit aside, wiggled for space. It took Liesl a moment to realize that the five tiny heads all belonged to one hand. Filth crusted the fingernails and knuckles, but the flat palm shone. The hand’s twisting made something go cold inside her, and she backed up a step, bashing into one of the shelves Hans had carefully organized for their air raid shelter. The boys ignored her.

“You’re through,” said Ani, and he reached out formally and shook the hand. It engulfed his fist up to the wrist. “Welcome to our cellar, Herr Geiss.”

“Thank you, young man,” said a gruff, muffled voice, and the hand retreated.

“It’s Herr Geiss,” Ani said, finally acknowledging Liesl’s presence. “He’s connecting us.”

“Connecting who?” said Liesl.

“Us. Cellar to cellar,” said Ani.

Metal glinted in the hole again. “Good morning, Frau Kappus,” said the voice.

“I don’t know what your father will say about this,” said Liesl.

“It’s for our safety,” interrupted Hans. “People can get trapped. It happened in Kassel and Darmstadt. If we neighbors adjoin our cellars, then we have a better chance of survival. Everyone knows that.”

“But a hole might weaken the wall.” Liesl put her hands on Ani’s shoulders and pulled him back. “Herr Geiss, I must ask you to cease this until I correspond with my husband—”

She heard her voice falter as the spade continued to work, as Ani shook free and hurried to the crack again, breathing into it. Two weeks ago, Liesl had woken to the thumps of Herr Geiss sandbagging both their roofs, clambering from red tile to red tile on his thick old legs. She knew he called her the “young wife,” as if Susi were still alive and Frank had somehow acquired an auxiliary spouse. She knew that Herr Geiss was the reason Hans never got caught for poaching kindling from the willows in the Kurpark. Herr Geiss had ties high up in the Nazi Party, and people feared him. He had been Frank’s neighbor since Frank’s boyhood. He had helped delay the surgeon’s deployment after Frank’s first wife had died. Every week, he gave Liesl extra ration cards, ones meant for his widowed daughter-in-law, his only living relation, who refused to leave Berlin.

Yet Liesl also knew that Herr Geiss didn’t trust her. Herr Geiss had told Frank that if his “young wife” did not watch his boys well, he’d see them safely away from her, to a farm in the country. All over Germany, families were splitting up in order to protect their children, but Liesl couldn’t bear the idea, and had told Frank so.

“He won’t send anyone away,” Frank had scoffed. “He likes you.”

One afternoon following a thunderstorm, she’d opened the gray living room blinds to see Herr Geiss looming over their house from his second floor. At the sight of her, he’d flinched, then frowned. She’d blushed, suddenly aware of her narrow hips, her red springy hair, and their contrast to Susi’s blond, groomed curves. The young wife. Or maybe the wrong wife.

“It’ll weaken the wall,” she said again, over the scraping.

There was a grunt. “I’ll brick it up after I make the hole,” Herr Geiss said. “You’ll hardly know it’s there.”

The basement light stripped the flush from the boys’ skin and accentuated their skulls. Even plump-cheeked Ani looked like a statue poured from molten metal, his rosy lips darkened to brass. She realized that she’d never heard the boys laugh down here.