Moyra Caldecott

Authors: Etheldreda

Etheldreda

Moyra Caldecott

Mushroom eBooks

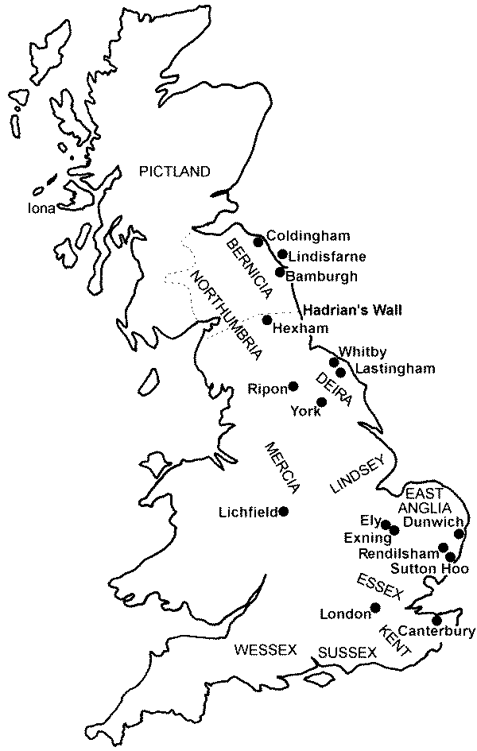

England in the seventh century was a place of violence and conflict. The seven kingdoms of the Germanic tribes were warring against each other and against the native Celts. Occasionally an uneasy peace was bought by the skilful use of the diplomatic marriage. Pagan Mercia was ruthlessly dedicated to expansion and to stamping out Christianity. Within the Christian kingdoms themselves there was the clash between the organized Roman Church and the much more individualistic Celtic form of worship from Iona and Lindisfarne.

Through all this, the four remarkable daughters of Anna, King of the East Angles, fired by the ideals of a new and revolutionary religion, managed not only to hold their own, but also to emerge head and shoulders above most of the people of their time.

One of them, Etheldreda, became Queen of Northumbria during the golden age of its power and was later declared a saint, her shrine at Ely near Cambridge the centre for miracles even into the present century.

As a young girl she felt herself called to be a nun and vowed chastity, but politics intervened and she was twice married to save her father’s kingdom. Once to Prince Tondbert, ruler of the wild fen country around Cambridge, a man much older than herself, and later, at his death, to Prince Egfrid of Northumbria, a boy of fifteen. Faced with the violent deaths of those dearest to her and with upheaval and treachery on all sides, she not only endured, but ruled Northumbria with strength and wisdom for many years.

When she was in her early forties and Egfrid twenty-five, he refused to accept the arrangement he had agreed to honour when he married, and tried to force her to bed with him. She fled. He and his men gave chase. After an extraordinary journey south in which storms seemed to intervene on her behalf, she escaped at last to the Island of Ely, which had been her first husband’s marriage gift to her, and there founded a religious community.

Bitterly King Egfrid gave up his claim to her, throwing her friend Bishop Wilfrid, who had supported her bid for freedom, into a dungeon and embarking on a series of punitive wars against his neighbours to the north and across the sea in Ireland. But this is not just the story of war and treachery in early England. It is about the general human struggle to comprehend the enigma of existence and to come to terms with Christ’s God, faced as we are by a violent and cruel world. It is about the periods when we give up the struggle, reverting either to the darkest negativity or to superstition – and the rare but wonderful periods when we are lifted high by the inrush of spiritual certainty.

Edwin holds a council with his chief men about accepting the Faith of Christ, AD 627:

‘Your Majesty, when we compare the present life of man with that time of which we have no knowledge, it seems to me like the swift flight of a lone sparrow through the banqueting-hall where you sit in the winter months to dine with your thanes and counsellors. Inside there is a comforting fire to warm the room; outside, the wintry storms of snow and rain are raging. This sparrow flies swiftly in through one door of the hall, and out through another. While he is inside, he is safe from the winter storms; but after a few moments of comfort, he vanishes from sight into the darkness whence he came. Similarly, man appears on earth for a little while, but we know nothing of what went before this life, and what follows. Therefore if this new teaching can reveal any more certain knowledge, it seems only right that we should follow it.’

From

A History of the English Church and People

by Bede (Penguin Classics, translation by Leo Sherley-Price, 1955), Book II, Chapter 13.

War AD 640

To the defenders of Egric’s dykes, Penda’s warriors seemed numberless.

All day they came.

Time after time the air was filled with the high deadly whine of arrow flight, the scream of the wounded, the barbarous battle shout of the enemy. Where the dykes were most easily breached, at the point where the trade road to the south-west crossed the great ditch on ramp and wooden bridge, the fighting was hand to hand, Penda wielding his battleaxe as though he were cutting the tall wheat at harvest time. The Seer he had consulted had promised him that much blood would be spilt, but that not much of it would be theirs.

The invading Mercians had few casualties. The hapless East Anglians, defending their homeland, had more than they could count.

Before the last great dyke the Mercians paused. Evening was coming on fast, and the sun was staining the sky with a reflection of the blood that they had shed upon the earth. Penda called back his men to rest and gather strength, intending to take the dyke at dawn. They made camp, roasting the cattle they had taken from their enemies, drinking the ale they had brought with them from their homeland.

Two young princesses of the East Anglian court, Etheldreda and Saxberga, daughters of Prince Anna, were far from home, staying with relatives. The first they knew of the Mercian invasion was the sudden arrival of terrified refugees making for the fenlands, preferring to take their chances with the ghouls and demons that inhabited those mysterious regions than be put to the sword or split by the axe. Behind the refugees the princesses could see the black smoke as village after village across the land was set on fire.

Panic-stricken, the princesses’ relatives hastily packed up all they could carry of their possessions, and the girls joined them in a dash for the east. They hoped that they would reach the final dyke and be allowed over the ramps before they were closed for battle.

At the last ford before the dyke, where the crowds of hysterical people were struggling against each other in the effort to get to the other side, Saxberga was knocked off the horse she was sharing with Etheldreda and trampled under its hooves. Screaming for her sister as she saw her go under, Etheldreda flung herself after her and tried to drag her clear. The horse was instantly seized by someone else and ridden off; the two girls, separated from their friends, were left in the muddy water among the pushing, violent people.

Etheldreda was weeping and trembling, but she would not let her sister go for fear of losing her. She managed to drag her unconscious body somehow across the river and out of the path of the stampeding cattle, people, horses and carts. She called for help, but no one came to aid her. She stared in astonishment. It was only the day before that these same people had been bowing with respect to her and her sister as they rode high and fine upon their royal horses. The sun had shone on peaceful fields of yellow buttercups. Cows had grazed and chewed on the cud.

Now it was as though she and her sister were invisible. Torn and muddy and bedraggled, they were indistinguishable from the peasants and slaves who drove the farmers’ cattle across the ford and, for the first time in her life, she knew that she was on her own, that her survival depended entirely on her own ingenuity. She could not even turn for help to her older sister.

She stopped crying and looked around her. A little further on to the left was a wood; this would give them hiding place and shelter. She knew that they had to get away from the terrified mob, who were almost as destructive as the invading hordes from which they were fleeing.

Little by little she half dragged, half carried her sister to the wood, and did not rest until they were deep inside and well out of sight of the crowds and the distant columns of smoke. There she carefully made Saxberga as comfortable as she could on a bed of bracken, and carried water from a tiny trickling stream in her hands to splash into her face.

Saxberga regained consciousness with a jerk, and screamed with the pain she felt in her leg. Etheldreda flung her arms around her and held her tight.

‘We’re safe,’ she whispered, the tears she had held back for so long beginning to flow.

Saxberga’s face twisted with the pain, but she tried to pull herself together for her little sister’s sake.

‘What is happening?’ she asked. ‘Where are we?’ She could hardly bring the words out as she struggled to make sense of the situation.

‘We’re safe,’ Etheldreda babbled on. ‘No one will find us here, we’ll wait until the fighting is over.’ The tears ran through the dirt on her cheeks unnoticed.

Suddenly they heard a movement behind them and swung round, horrified to find themselves observed by a strange, rough youth clad in skins, his hair and eyes dark, a dead deer over his shoulder. Etheldreda seized a stone that was lying next to her hand and clutched it, ready to use it as a weapon if necessary.

He took a step nearer, staring at them curiously. She shrank back. Was this one of the dread heathen Mercians? He certainly was not of their own race, though he did not look as fierce and cruel as they expected. Perhaps he was one of the native people, a Celt. She moved away from Saxberga and stood up straight, like the princess she was, looking him in the eye.

‘We need help,’ she said, trying to keep her voice steady and cool. ‘Will you help us?’

He looked her up and down. She was covered in mud from the ford and blood from her sister; her hair was matted and hanging in strings; her pale, dirty face was pinched with weariness and anxiety, but she spoke as though she expected to be obeyed like one of the hated Angles who had invaded his land and made a slave of him. He almost turned away and then his eyes fell on the girl in agony on the ground.

‘Where are you hurt?’ he asked gruffly, his accent strange to them, but his voice not ungentle. Etheldreda silently pointed to the bone protruding from her sister’s leg and he put the carcass of the deer down in the bracken and crouched down beside them, looking thoughtfully at Saxberga’s leg.

From somewhere in the distance they heard a terrible scream.

‘Haven’t you heard of the war?’ Etheldreda asked him. ‘You don’t seem to be running away like everyone else.’

‘Yes, I have heard of the war,’ he said as though it was of no importance. Then – ‘You take the deer,’ he said to her, and put his arms around Saxberga to lift her from the ground. ‘Come.’

Etheldreda looked with horror at the animal that she was expected to carry.

‘Come,’ he said again, urgently, commandingly.

Etheldreda tried to swing the carcass to her shoulder, but she almost fell over with the weight.

‘Can’t I leave it?’ she pleaded.

‘No. Bring it,’ he said roughly, already moving away through the wood.

Terrified of being left alone, she took a grip on the deer’s antlers and dragged the body behind her, tugging and struggling as it caught on fallen branches and tough little bushes. Not once did he look back to see if she was managing to keep up with him.

When he finally stopped walking and lowered Saxberga to the ground, Etheldreda was sweating and exhausted, but determined not to cry. They were deep in the thickest part of the wood, the undergrowth of brambles making the way almost impassable. He started to bend back branches, and she discovered that an overhang of rock made a sizeable cavern behind a wall of bushes. He indicated that she should go ahead, and when she had crept and scrambled and slithered her way in, he carefully lifted her sister in after her.

Etheldreda looked around her. There was a small lamp cut out of the chalk, with a rush wick and, by the smell of it, animal oil; earthenware pots and jugs, and the blackened stones of a small hearth fire. There was also a pile of straw with furs flung over it, onto which he now lowered the older girl. He then left them for a moment to attend to the deer carcass the child had left exposed outside.

Etheldreda crouched down beside Saxberga and held her hand tightly. It was very dim in the cave, but as her eyes grew accustomed to the lack of light she noticed the grotesque figure of a heathen god staring at her from a niche in the rough wall. Seven-branched antlers grew from his head and a garland of leaves hung around his neck.

That night as Penda tried to sleep in his tent of skins he heard a terrible sound. Only half awake he went to the entrance of his tent. The battlefield of the day before, still covered with the bodies of the slain, lay behind him. Above him the sky was swirling with dark clouds, and from the wind came a wild keening. Could he see the women of death riding the clouds, crying high and loud, calling the names of the warriors who had died and would die… and behind them the hounds, howling across the sky?