Mr Briggs' Hat: The True Story of a Victorian Railway Murder (16 page)

Read Mr Briggs' Hat: The True Story of a Victorian Railway Murder Online

Authors: Kate Colquhoun

Tags: #True Crime, #General

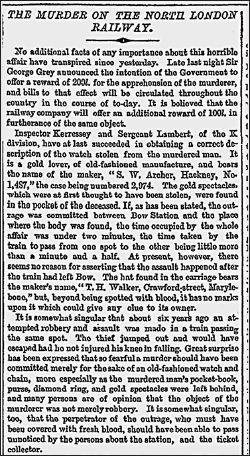

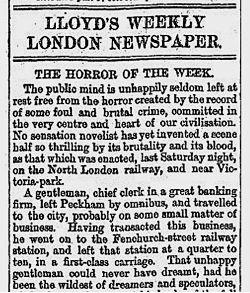

Liverpool Mercury

, 20 July 1864.

The Times

, 12 July 1864.

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper

, 17 July 1864.

National and regional newspaper headlines

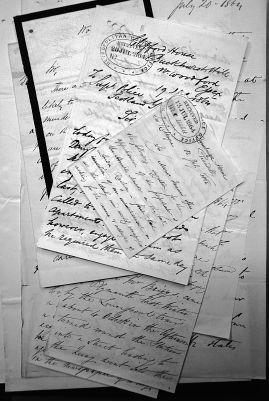

One of Superintendent William Tiddey’s expense forms. On 23 July he paid for several omnibus and cab fares, for Müller’s lodgings to be searched and for the dust hole at 16 Park Terrace to be emptied.

Letters addressed to the police, containing advice or airing suspicions, arrived from all over the country.

The London Docks, 1845. On the left, the North Quay and its warehouses, and on the right the River Thames snaking out towards the English Channel.

Steamship

The City of Manchester

, the boat Tanner took on his chase to New York.

Several drunks in different districts of the capital had

begun to confess

to the murder. Hauled up in front of magistrates, all of them were judged to be lunatics or serial fabricators. Letters about being imprisoned in railway carriages with the delirious, the threatening or the downright odd still filled the papers and there were reports that one of the City’s most eminent young solicitors, Thomas Beard, boarding a train at Fenchurch Street, had been alarmed by a sinister co-passenger staring covetously at his watch and chain while quizzing him about the recent murder. The tall, black-clad man appeared to be concealing a leather-covered cosh.

Sick with fear

, Beard had leapt out at the next station and raised the alarm,

thoroughly convinced that a murderous outrage was purposed

.

Newspaper reporters speculated on the progress of the ships crossing the Atlantic, couching their conjecture in prose worthy of a suspense thriller. The London detectives and their two witnesses were heading towards a divided nation exhausted by three years of hard fighting, to a country in which casualties mounted in their tens of thousands, where the price of food, fuel, clothing

and rent forced many into poverty and where the scent of war suffused the air.

The Times

reported that Müller’s ship,

the

Victoria

, was making little headway

against strong headwinds and high seas. By the end of July, nearly a fortnight after leaving London, she had only just reached Cape Clear off the coast of southern Ireland.

In New York, sketchy details of the London railway murder began to trickle into the press. Confined to the earliest-known facts, they communicated simply that a gentleman in a first-class carriage had been severely beaten and

flung, in a matter of minutes

, onto the tracks by an assailant who left no material clue. What they did not yet know was that the suspected murderer was en route to their city, pursued by Metropolitan Police detectives in two separate ships. As new details of the Briggs case emerged, the story would grow from a small foreign news report into a New York City talking point.

*

Unlike the

Victoria

, Inspector Tanner’s

City of Manchester

had powered across the ocean. Sixteen days after leaving Liverpool the vessel navigated the final stretches of New York’s harbour. Slipping past Governor’s Island on the morning of Friday 5 August, she edged through a forest of masts and a clamour of packet ships, clippers and ocean steamers to reach her dock on the south-western edge of Manhattan Island. Three days into the voyage, Tanner had fallen down a companionway ladder and was under the care of the ship’s surgeon,

in severe pain

. Once in port he was assailed by the heat and the shouts of the stevedores, the crush of the passengers, porters and relatives who seethed between cargo hauls and luggage stacks. Only when he and his three companions had cleared quarantine and immigration did the London detective manage to establish that the

Victoria

had not yet been seen.

Passengers from the

Manchester

streamed through Castle

Clinton, the old stone fort on the water’s edge in lower Manhattan used as an immigration station, registering their arrival while some changed their money, sought directions or prepared to sleep on the floor for a night or so until they got their bearings. His formalities completed, Tanner hailed a horse-drawn cab for the group including John Death, Jonathan Matthews and Sergeant Clarke. Quitting the riverside stink, the foundry stacks, the groaning wharves and packing sheds, they left the Hudson River docks in their wake, pushing through a snarl of laden wagons to gain the southern edge of Broadway. Here they headed north, rumbling past a confusion of narrow lanes and slums as they made their way towards the centre of the city.

As the warren of southern streets gave way to the twelve parallel avenues that stretched northwards as far as 44th Street, old timber villages were being replaced by distinct stone precincts. All that existed above 44th Street were surveyors’ pegs stuck into the baked mud and taut lines of string that marked out the city’s plans for expansion. Up at the line proposing 59th Street, a vast wilderness of 760 acres was earmarked as a park for a population that was growing so fast that it had

quadrupled in the three decades

since 1830. For now, though, everyone was packed into the southern reaches of the island; everything here, exclaimed the visitors’ guides, was

din and excitement.

Everything is done in a hurry

…

[and]

all is intense anxiety

.

Heading uptown, Tanner’s cab passed the crowds of black-suited bankers and merchants in Wall Street. A little further along on their right they reached the eleven-acre triangle of an area known as The Park with a central fountain in the shape of an Egyptian lily throwing columns of water up into the dusty air. This was the civic centre, margined by imposing public buildings and dominated by the marble-columned façade and lofty clock tower of City Hall. To the left were the five-storey offices of the

New York Times

and, behind City Hall on Chambers Street, the United States District Court.

Union soldiers mingled with watermelon and pineapple vendors in the New York streets. After sixteen days at sea,

Broadway was bewildering

, alive with snapping reins and shying horses, fine shops, bright clothes, vagrant children, burly cops and advertisements for Phineas T. Barnum’s American Museum with its giants, dwarves, Indian warriors and French automata. Small entrances to oyster cellars vied with the grander façades of glittering eating houses such as Taylor’s and Maillard’s Saloons and the renowned Delmonico’s. Horse-drawn locomotives ran on tracks right down the middle of streets. Passing under humming telegraph wires, the cab pushed its way through an entanglement of carriage wheels and carts.

Tanner’s destination was the

Everett House Hotel

at 17th Street on the north side of Union Square, a hotel that advertised itself as usefully positioned for the centre of town, the cars and the stage coaches – New York’s equivalent of the London omnibuses. It would be their base for the foreseeable future. Transplanted into this crucible of half a million strangers, Tanner, Clarke, Death and Matthews were foreigners in a city of immigrants. It was late afternoon. Tomorrow, Tanner would begin his official calls.

He would find that fuller details of the Briggs murder had begun to appear in the New York press, the American papers explaining that

English railcars

are very different from those to which we are accustomed in this country

, as journalists lingered over their comparative isolation. They emphasised the disappearance of Thomas Briggs’ watch and sprang on the evidence both of the jeweller John Death and of the cabman Jonathan Matthews. It was now apparent that the suspected murderer was bound for their city and that

witnesses were also expected

imminently, in the company of at least one Scotland Yard detective.