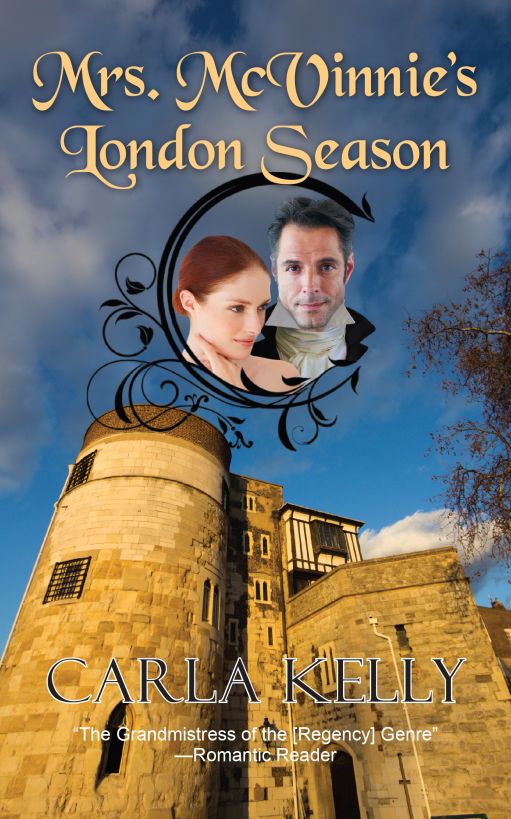

Mrs. McVinnie's London Season

Camel Press

PO Box 70515

Seattle, WA 98127

For more information go to: www.camelpress.com

www.carlakellyauthor.com

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be

reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic

or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any

information storage and retrieval system, without permission in

writing from the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places,

brands, media, and incidents are either the product of the author’s

imagination or are used fictitiously.

Cover design by Sabrina Sun

Author Photo by Bryner Photography

Mrs. McVinnie’s London Season

Copyright © 1990, 2014 by Carla Kelly

First published in 1990 by Signet, an imprint of

Penguin Books USA, Inc.

ISBN: 978-1-60381-955-8 (Trade Paper)

ISBN: 978-1-60381-956-5 (eBook)

Library of Congress Control Number:

2014938125

Produced in the United States of America

* * *

Had we never lov’d sae kindly,

Had we never lov’d sae blindly,

Never met—nor never parted,

We had ne’er been broken-hearted.

—

Robert Burns

* * *

S

he heard the postman’s whistle at her own front door

almost before she turned the corner and set her feet toward Abbey

Head. Jeannie McVinnie stood still a moment in the roadway. She

nodded to the other women, baskets over their arms, who were headed

in a purposeful cluster toward the greengrocer’s. After another nod

and a bow to the minister’s new bride, Jeannie twitched her plaid

up a little higher about her shoulders and continued on down the

street.

She was not the kind of

woman who backtracked. Jeannie no longer believed her mother’s

admonition that to turn back, once having set out, would bring down

all manner of misery and bad fortune. She was not superstitious,

but still, she would not have retraced her steps.

Besides, Galen was

there, and in a grumpy mood. It would do him good to stir from his

armchair, where everything was laid out within easy reach, and

hobble to the front door. Now that his color was much improved and

his melancholy in large part gone, Jeannie felt compelled to force

a little exertion upon her father-in-law. He had no cause to chafe

about the fit of his wooden leg. The surgeon had declared the

amputation a thing of beauty, going so far as to summon his

colleagues from the University of Edinburgh to exclaim and proclaim

until Galen McVinnie was heartily tempted to unstrap the leg and

beat the physics about the head with it.

A walk to the door

would do him good, she told herself as she turned her head against

the little mist that seemed to rise from the ground. She paused

again and considered tramping over the road past the church and

toward Gatehouse of Fleet. She discarded the notion; the

rhododendrons were not yet in bloom. She would wait for that

event.

Jeannie turned again

toward Abbey Head. It was a walk of some five miles, affording

ample time for reflection, but not too much. She did not trouble

herself about the letter. Undoubtedly it was for Galen McVinnie,

late a major of His Majesty’s Fifteenth Dumfries Rifles. For the

past year as the shocking news had spread farther and farther away,

like a pebble tossed into Wigtown Bay, letters had dribbled in.

When Galen could not

raise his head off the pillow, Jeannie had answered the first spate

of letters, stopping often because she could not see through her

tears to write. Calmly she accepted the condolences of Tom’s death

and the prayers for Galen’s speedy recovery.

During those dark days

of the Scottish winter, Jeannie McVinnie had come to dread the

postman’s whistle. It only meant more letters, more explanations.

When Galen could sit upright again and his handwriting was steady

enough, she gladly surrendered the correspondence to him.

Her father-in-law kept

up a series of letters to particular friends, and as the year of

mourning wore on, the missives of concern turned into invitations

to visit. Only yesterday there had been a note scrawled on quite

good rag paper and franked by a lord, requesting his attendance at

a regimental gathering in Dumfries.

“

It is

not very far, Jeannie,” Major McVinnie had said, and there was

something wistful in his voice that made her turn her head so he

could not see her smile.

“

Indeed not, Father McVinnie,” she had replied, knowing better

than to attempt to make up his mind for him. Thomas had been woven

of the same plaid; and she had learned early in her brief tenure at

marriage not to press the issue.

In the end, last night

Galen decided against the gathering. “Jeannie, too many questions,”

he said as he refolded the paper and laid it aside. “Perhaps some

other time.”

But she had found him

looking at the note again before she escorted him upstairs to bed

that night. “Still, I could not leave you here alone, my dear, now

could I?”

His words were kind;

they were always kind. But more and more, it was that condescending

kindness of the strong for the weak. He was measuring her each day,

and finding her lacking, even as he smiled. He watched her when he

thought she wasn’t aware, but she was always aware. And what he

saw, he did not like.

The mist lifted and

allowed the sunshine to stream through the clouds. Jeannie turned

her face toward it. She knew it would be brief. March sunlight

served only to keep heart in the body until spring’s tardy arrival

to the lowlands. She took a deep breath, mindful that already there

was something of spring in the air.

“

The

spring of 1810,” she said out loud, as if to allow it official

recognition. The spring of 1809 had passed without fanfare, other

than to be marked with an X on each calendar square, the symbol of

one more day got through without Thomas McVinnie.

An hour’s brisk walk

brought her to the head, crowned by the ruins of an abbey. It was

too early in the year for the young ladies of St. Andrews’ Select

Female Academy to be grouped here and there about the picturesque

stones, their heads bent diligently over sketching pads, so she had

the place to herself. Even the sea gulls normally in residence were

wheeling far overhead on the air currents.

In a moment she had

perched herself into the shell that had once formed a window

overlooking the bay. She sat still, reflecting, not for the first

time, on the quality of Scottish woolens, effective even against

cold abbey stones.

Jeannie smiled to

herself, remembering again that over oatmeal that morning Galen had

looked at the invitation from Dumfries. “I wonder, my dear, if that

part of the regiment from Canada—Bartley’s company—will be

there.”

A sea gull, irritated

at the intrusion upon the abbey, swooped lower to investigate.

Jeannie took one of last night’s scones from her pocket, crumbled

it, and tossed it toward the bay. The sea gull ignored her for

several more moments and then condescended to alight and peck among

the stones.

Jeannie sighed and sunk

her hands deep in her pockets. Galen McVinnie was restless to go to

Dumfries, but he would make no move as long as she remained with

him in Kirkcudbright. It was time for her to move along. Galen

still had a life to live, even if hers was over.

“

And

where might I move to, may I ask?” she questioned the gull, which

hopped a few steps farther away and regarded her with a red

eye.

Mother and father were

dead long since. Agnes had dutifully invited her to join them in

Edinburgh, but Jeannie knew the size of her sister’s house and just

as politely declined. Her two brothers served in India. They had

invited her to the subcontinent, but she did not relish a long sea

voyage. She was not very fond of water.

But it was more than

that; she knew it and her brothers knew it. At the end of the long

journey, there would be row upon row of officers ready to propose,

eager to marry a white woman from Britain, all the more so if she

were not hard to look at and moderately endowed. Jeannie McVinnie

was not ready to cast herself upon the marriage mart so soon after

Thomas’ death.

“

Surely you will agree, friend bird,” she said to the gull,

which hopped closer, “that the consideration of one’s second

husband is possibly a matter for some serious thought. And I choose

not to think about it yet. India can wait.”

If it was not to be

India, what, then? She knew she must remarry. It was a cold-blooded

reflection that had cost her many a night’s sleep. The knowledge

that she was destined to marry again, duty-bound, had chased about

in her head until she was weary of it. And always by the time

morning came, she was fully awake to the fact that she had no

desire to sleep in anyone’s arms but Tom’s, and now it was too late

for that.

Jeannie hopped down

from the ledge and shooed the gull away with her skirts. It rose in

an indignant fluff of white, hissing at her, as she walked closer

to the cliff overhanging the bay.

A small boat of

indeterminate type tacked across the bay, searching about for a bit

of wind to bring it safely in. Jeannie shaded her eyes with her

hand and watched it.

I would be a sailor,

she thought suddenly, and let the wind blow me where it chose. She

sighed. If only I could feel some harmony with the sea.

But she would never be

a sailor, or a soldier, or a doctor like her father, or a

greengrocer, or a vicar. The only path open to her was marriage. As

she stood watching the boat in the bay, Jeannie decided to

entertain the notion. Somewhere in the wide world, there must be

another man for her. She might not love, but she could like.

“

And

he needn’t be handsome,” she told the gull, which had plummeted to

earth again, chattering and scolding behind her back. “One cannot

have such good fortune twice in a row. He must be amiable, however,

and good-natured and polite. A wealthy man would be an excellent

thing, too.”

The thought made her

smile. “Where you expect to find a wealthy man, where none existed

before, I cannot imagine, Jeannie,” she told herself.

She walked back to the

abbey ruins and leaned against the ledge. “And while I am about it,

he should be wondrous fond of children and devoted entirely to the

finer things in life.”

The idea was so

improbable that she laughed out loud, noting with surprise that it

was the first time in a year she had done so. “Such a paragon I

have created,” she told the gull. “The wonder of it would be if

such a man old enough for me was still safe from Parson’s

Mousetrap!” It felt good to laugh, and she was still smiling to

herself as she set her face toward Kirkcudbright again and the

little stone house on McDermott Street.

Mrs. MacDonald was out

to market when Jeannie returned. The housekeeper had vowed after

breakfast to come home with a joint of mutton, “or die in the

attempt, Mrs. McV,” she had declared as she put on her hat and

battened it down in anticipation of Kirkcudbright’s wind.

The subject was a sore

one, and Mrs. McDonald was not one to let a topic wither without a

good shake. “Although why it should be so hard to get a good joint

of mutton in Scotland, I canna fathom. Do our soldiers in Spain eat

so much that there’s not even a dab left for pepper pot? Explain it

to me again, Mrs. McV.”

And Jeannie had

patiently explained again that wartime causes shortages of the most

inexplicable commodities, even mutton in Scotland.