Muhammad Ali's Greatest Fight (19 page)

Read Muhammad Ali's Greatest Fight Online

Authors: Howard Bingham,Max Wallace

In 1658, a Maryland Quaker named Richard Keene became the first conscientious objector in American history when he refused to participate in the colonial militia because his religious beliefs opposed military activities. Like Keene, most of the other early conscientious objectors were Quakers and Mennonites, who believed the Bible forbade them from participating in wars of any kind.

The first nationwide draft by the U.S. federal government came in 1863, during the American Civil War. President Lincoln was sympathetic to conscientious objectors and introduced legislation that acknowledged the validity of their objections and permitted them to perform public service in hospitals as an alternative.

During World War I, many objectors refused to cooperate with the war in any way, including alternative service, and the War Department ordered all conscientious objectors court-martialed. Of the 450 who were found guilty, 142 were sentenced to life in prison.

In 1917, the Draft Act officially exempted men who objected to war for religious reasons, but the exemption applied only to those who belonged to a “well recognized religious sect or organization … whose existing creed or principles forbade its members to participate in war in any form.”

During World War II, 72,000 Americans requested objector status and more than 6,000 were sent to prison for refusing alternative service, including Elijah Muhammad and many of his followers.

During the Korean War, Malcolm X had registered as a conscientious objector. He later recounted his response when officials asked him if he knew what the term meant: “I told them that when the white man asked me to go off somewhere and fight and maybe die to preserve the way the white man treated the black man in America, then my conscience made me object.”

The Vietnam War created a new type of conscientious objector, one who did not condemn all military activities, just a specific war. This provided a new challenge for the courts to interpret the validity of an individual’s objection.

When Ali’s legal team filed its first request for draft exempt status in February 1966, it stuck to strictly procedural grounds. But on March 17, Ali appeared before the Louisville Draft Board with a new argument. Once again he testified that his parents would suffer undue financial hardship if he entered the army and earned only eighty dollars a month. But for the first time, he invoked his religion, saying that the Holy Koran forbids Muslims from fighting wars on the side of unbelievers. The presiding officer was skeptical and questioned his famous applicant’s sincerity.

“I am sincere in every bit of what the Holy Koran and the teachings of Elijah Muhammad tell us and it is that we are not allowed to participate in wars on the side of non-believers,” Ali responded. “This is a Christian country, not a Muslim country, and history and the facts show that every move towards the Honorable Elijah Muhammad is made to distort and to ridicule him….We do not take part in any part of war unless declared by Allah himself or unless it’s an Islamic World War, or a Holy War, and we are not to even so much as aid the infidels or the non-believers in Islam….This is not me talking to get the draft board or to dodge nothing.”

Back in Washington the Johnson White House, the FBI, and the military establishment watched Ali’s actions nervously. Anxious to deflect the fallout, newspapers in cities with large black populations were issued press releases reflecting the government line. The

Atlanta Journal

carried a story that unwittingly helped make the case for black critics of the war: “Pentagon officials are praising the Negro as a gallant, hard-fighting soldier. New figures show that proportionately more Negro soldiers have died in Vietnam than military personnel of other races.”

In fact, more than 29 percent of all soldiers who died in Vietnam that year were black, even though Blacks made up only 11 percent of the country’s population. At the same time, large numbers of middle-class whites were being exempted from military service because of student deferments, prompting Stokely Carmichael to charge, “Blacks are being used as cannon fodder for a white man’s war.”

In late March, Ali’s draft exemption request was again denied, prompting an appeal six weeks later before the Kentucky Appeal Board. By law, before the appeal board could make a decision, it was required to refer Ali’s file to the U.S. Justice Department for an advisory recommendation. This would require a special hearing at which the appellant would be allowed to testify and call witnesses.

Hearing the case would be a retired Kentucky judge named Lawrence Grauman. In order to prevail, Ali would have to convince Grauman of his “character and good faith.” He would also have to satisfy three basic tests of conscientious objector status as set out by the Selective Service Act. First, he must show that he is conscientiously opposed to war in any form. Second, he must show that this opposition is based on religious training and belief, as interpreted in two key Supreme Court rulings. Third, he must show that his objection is sincere.

Since his announcement two years earlier that he had joined the Nation of Islam, the FBI had compiled an extensive dossier on Ali, documenting his public statements, his friends, and his travels. These were based mostly on newspaper clippings and information supplied by informants. But in May 1966, J. Edgar Hoover ordered Ali to be placed under official FBI surveillance—the first boxer so honored since Jack Johnson, fifty years earlier.

Agents interviewed more than thirty-five friends, acquaintances, and family members. According to the FBI report, “These people all spoke highly of Clay and none of them provided any information that would have supported a denial of his [conscientious objector] claims.” While Hoover himself was consorting with mobsters, gambling heavily, and engaging in a homosexual relationship while purging gay agents from the FBI, the thorough investigation turned up nothing more damaging against Ali than seven traffic violations over a five-year period. This information was turned over to the appeal board, along with a report that Ali had purchased a gun at a Miami pawn shop in 1964—which a member of his entourage promptly threw into the ocean—and a summary of Ali’s recent appearance on the

Tonight Show,

hosted by Johnny Carson.

On August 23, 1966, the special hearing was convened. After Grauman heard from Ali’s parents and a minister from the Nation of Islam, the reluctant recruit testified under oath:

Sir, I said earlier and I’d like to again make that plain, it would be no trouble for me to go into the Armed Services, boxing exhibitions in Vietnam or traveling the country at the expense of the government or living the easy life and not having to get out in the mud and fight and shoot. If it wasn’t against my conscience to do it, I would easily do it. I wouldn’t raise all this court stuff and I wouldn’t go through all of this and lose the millions that I gave up and my image with the American public that I would say is completely dead and ruined because of us in here now. I wouldn’t jeopardize my life walking the streets of the South and all of America with no bodyguard if I wasn’t sincere in every bit of what the Holy Koran and the teachings of Elijah Muhammad tell us and it is that we are not to participate in wars on the side of nonbelievers. We are not, according to the Holy Koran, to even as much as aid in passing a cup of water to the wounded. This is there before I was born and it will be there when I’m dead and we believe in not only part of it, but all of it.

Since his first draft exemption request, the Nation of Islam had secured the services of a lawyer named Hayden Covington Jr., who had made his reputation successfully representing Jehovah’s Witnesses seeking religious deferments during World War II. When he took on Ali as a client, Covington decided his previous lawyers had made a fundamental error in strategy. Initially, they had applied for conscientious objector status, which—under the nation’s current laws—would have still required Ali to perform two years of alternative service in a non-combat role. Covington amended the request to seek exemption for Ali as a Muslim minister. Members of the clergy were exempted from military service of any form.

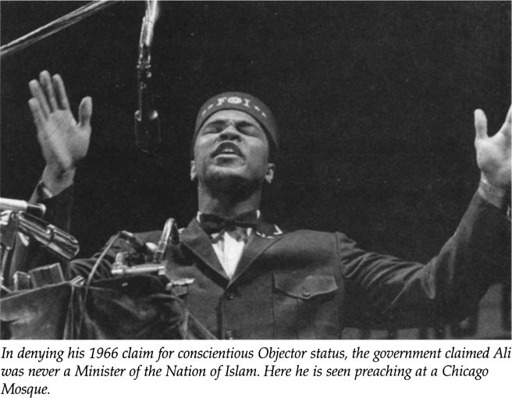

A convincing case could be made that Ali was a genuine minister. For more than two years, he had traveled the country preaching sermons at Nation of Islam mosques throughout the country. Thousands of Muslims heard him expound on his favorite topic, in what became known as the “pork-eating lecture,” about one of the faith’s greatest taboos. His repertoire included snuffling pig sounds and blackboard cartoons of “the nastiest animal in the world, the swine, a mouthful of maggots and pus. They bred the cat and the rat and the dog and came up with the hog.” After witnessing his sermons, it was hard to doubt that he was a legitimate minister. In front of Judge Grauman, he proceeded to make this case.

“You see this?” he said, holding up a copy of the Koran. “These are the writings which we Muslims believe are revelations made to Muhammad by Allah.”

He contended that 90 percent of his time was devoted to “preaching and converting people” and only 10 percent was taken up by boxing. “At least six hours of the day I’m somewhere walking and talking at Muslim temples and there are fifty odd mosques all over the United States that I am invited to minister at right now, and constantly.”

When Ali finished, Judge Grauman took a short break before delivering the judgment which would shock the hearing room, the United States government, and Ali himself.

I believe that the registrant is of good character, morals, and integrity, and sincere in his objection on religious grounds to participation in war in any form. I recommend that the registrant’s claim for conscientious objector status be sustained.

James Nabrit III, who would later join Ali’s legal defense team, described the general reaction. “Nobody expected the hearing to go for Ali. These things are usually pretty routine and they normally uphold the original decision. In this case, Ali was at his lowest point of popularity and he was arguing this religious doctrine which needless to say wasn’t very popular in a Christian state like Kentucky.”

Ali had been warned by his legal team that he was unlikely to prevail. When Grauman delivered his surprise judgment, he thought his grueling battle had finally come to an end. “For a very short time, I actually thought the system had worked,” Ali recalls. “When that judge said I was sincere, I thought he was supporting the principles of our faith, he was telling America that we were legitimate, that we had as much right as the Christians to our beliefs.”

But Grauman’s ruling was only a recommendation. In Washington, the Justice Department wasted little time ensuring that the Appeal Board ignored the judge’s opinion. It wrote a letter to the Selective Service Board arguing that Ali had failed to satisfy the most important tenet of conscientious objection—that he was opposed to war in any form.

“It seems clear that the teachings of the Nation of Islam preclude fighting for the United States not because of objections to participation in war in any form but rather because of political and racial objections to policies of the United States as interpreted by Elijah Muhammad …. These constitute only objections to certain types of war in certain circumstances rather than a general scruple against participation in war in any form,” wrote T. Oscar Smith, chief of the conscientious objector section of the Justice Department.

Pointing out that Ali had made no mention of his religious status at his first draft exemption hearing in February, the department argued that his beliefs were a matter of convenience and not “sincerely held,” manifesting themselves only when military service became imminent.

Two days after the hearing, the chairperson of the House Armed Service Committee, L. Mendel Rivers, addressed a convention of the Veterans of Foreign Wars in New York. He threatened a complete overhaul of religious deferments if Ali’s conscientious objector claim was upheld.

“Listen to this,” he bellowed. “If that great theologian of Black Muslim power, Cassius Clay, is deferred, you watch what happens in Washington. We’re going to do something if that board takes your boy and leaves Clay home to double-talk. What has happened to the leadership of our nation when a man, any man regardless of color, can with impunity advise his listeners to tell the President when he is called to serve in the armed forces, ‘Hell no, I’m not going.’”

After a lengthy delay, the appeal board issued its decision. Ignoring Grauman’s recommendation completely, Ali’s request for conscientious objector status was denied. He would have to report for induction when his name came up.

United States Attorney Carl Walker, who would later prosecute Ali, is convinced the board’s decision to deny the objector claim was political. “This is the only case I ever encountered where the hearing examiner recommended conscientious objector status and it was turned down,” he says. “At that time, I’m convinced the government truly believed they would have to make an example of Ali or it would start a chain reaction of black men refusing to join the army They were ignoring the Constitution—freedom of religion is very clear—and I thought it was wrong. But you have to understand those times.”