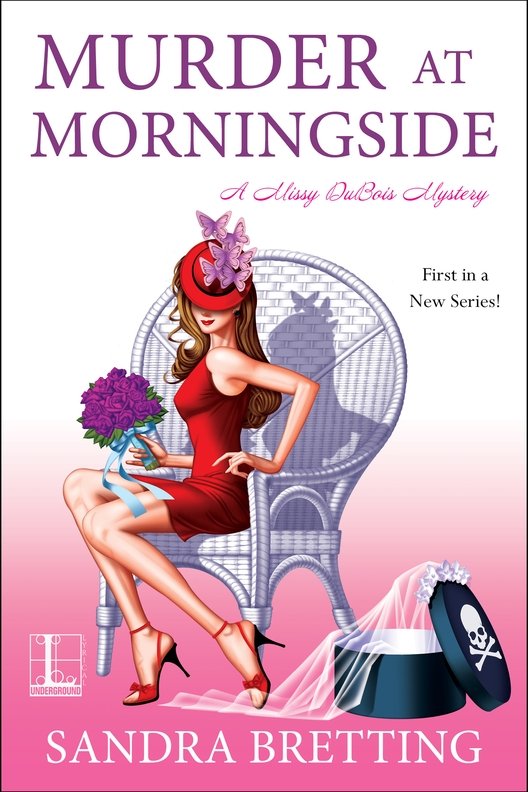

Murder at Morningside

Read Murder at Morningside Online

Authors: Sandra Bretting

MESSAGE FROM A KILLER

I stepped closer to my hotel-room door. The flower arrangement was more wide than tall, and it spread in front of the kick plate. My eyes had stopped watering, and I paused some twelve feet from the door. The colors were a jumble of greens, golds, and tans. But no cut flower I knew, even a fresh one, shimmered quite like that.

Plus, the arrangement seemed jagged, much too jagged for a professional bouquet. I crept a foot or two closer. Was that a feather sticking out from the top? It

was

a feather, although that didn't make much sense.

was

a feather, although that didn't make much sense.

I froze. My eyesight had cleared. It wasn't an arrangement of blooms and bulbs, leaves and stems. It was fabric, poking out from a greasy paper grocery sack. It had been left on the ground where I'd be sure to find it.

I forced myself to walk the last few feet to the door. I bent to pluck the feather from the sack. It was a quill, of all things. A pheasant quill, with barbs ripped out at random spots. A quill like the one used in Ivy's Victorian hat.

My fingers released the feather, and it twirled to the floor. Whoever destroyed Ivy's hat must have been angry, because the cuts were jagged, unplanned. They must have found the hat on the front porch, where I'd forgotten it once Lance arrived.

Why would someone destroy her beautiful hat like that? Even smashed, the hat was exquisite and obviously expensive. Now it sat in a ripped grocery sack, a jumble of tulle, ribbon and felt, topped with a bedraggled pheasant quill.

It was a message, obviously. Someone wanted to frighten me. I'd been holding my breath for the past few moments, which I slowly exhaled. If that was the person's goal, they'd accomplished their mission. . .

Murder at Morningside

A Missy DuBois Mystery

Sandra Bretting

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

For my daughters, Brooke and Dana. Because once upon a time we sat on your bunk beds and made up stories about a beautiful princess who lived in a faraway kingdom. Thank you for that memory.

Chapter 1

T

ime rewound with each footfall as I began to climb the grand outer staircase at Morningside Plantation. The limestone steps, burdened with the history of five generations, heaved their way toward heaven.

ime rewound with each footfall as I began to climb the grand outer staircase at Morningside Plantation. The limestone steps, burdened with the history of five generations, heaved their way toward heaven.

At the top lay a wide-plank veranda supported by columns painted pure white, like the clouds. By the time I took a third step, the digital camera in my right hand began to dissolve into the sterling-silver handle of a lady's parasol. The visitors' guide in my left hand magically transformed into a ballroom dance card bound by a satin cord.

Another step and the Mississippi River came into view as it flowed to the Gulf, languid as a waltz and the color of sweet tea. Could that be a whistle from a steamboat ferrying passengers past the plantation? If so, a turn and a wave wouldn't be out of the question once I reached the top of the stairs, and good manners would dictate it.

I was about to do that when I realized the whistle was only my friend's cell and not a Mississippi riverboat. “Ambrose! Turn that thing off. Honestly.”

“Sorry.” He shrugged. “I always forget you were Scarlett O'Hara in a past life.”

The mood was broken, though, and the sterling silver in my hand returned to plastic, while the linen dance card hardened to a glossy brochure. Ambrose patiently waited while I finished climbing the stairs.

Whenever we're out and about somewhere new, my best friend likes to go all out. Today he wore a striped bow tie and seersucker jacket from Brooks Brothers. Never let it be said Southern men didn't know how to dress. Of course, as a wedding-gown designer, he had more fashion sense than most, and his favorite motto was one could never be too rich or too fabulous, even though we both had more fabulous than money at this point.

“It's almost time for the tour,” Ambrose said.

I wasn't ready to release the fantasy, though. “Isn't it magnificent?” The veranda wound around the entire first floor, broad enough for a dozen wooden rocking chairs, most of which faced east. Black storm shutters framed the windows, like dark lapels on a white dinner jacket, and they matched an enormous front door with beveled glass. Suddenly the door swung open, as if to welcome its lost owners home.

“Welcome to Morningside Plantation.” A girl, probably a coed at nearby Louisiana State, appeared. “My name's Beatrice, and I'll be leading the four-thirty tour.” Her pleated skirt and starched collar were almost enough to make me cry with happiness, though I refrained. “Looks like you're my only guests today. Feel free to pretend you're staying here in the spring of eighteen hundred and fifty-five. By the way, I love your hat. Blue is my favorite color.”

It was lapis, but no need to nitpick. Obviously she had a good head on her shoulders. “Thank you. I made it.”

The girl ushered us through the foyer and into a glittery ballroom. Every curtain, the ceiling and the floors, not one but two fireplace mantels, all of it had been gilded to within an inch of its life. A parade of professional-looking wedding portraits marched along the mantels.

“May I have your tour tickets, please?” Beatrice asked.

“I was told the tour was included with our reservation.” Not that I wanted to speak for Ambrose, but I'd been the one to book our stay at the plantation. As soon as the bride asked him to design a custom gown and then turned around and asked me to create a one-of-a-kind veil, I called up to reserve our rooms for the weekend.

“You're staying at the plantation?” Beatrice waved her hand. “Then you're right. It's all included.” She drew closer, as if she wanted to share an important secret with me. “After the tour, I hope you'll peek around. There are nooks and crannies everywhere. Some people even say the mansion's haunted.” She smiled slyly before resuming her tour-guide pose. “This ballroom was painted pure gold on the orders of Horace Andrews. Even though the Victorians loved their color, he didn't want a bunch of bright colors to distract from his daughters' beauty.”

I must have looked a tad incredulous, because she rushed on. “That's what they say, anyway.”

“Is that the lady of the house?” I pointed to an oil painting above one of the mantels, which showed a gloved woman in a silk bodice who looked to be about my age. Or, as I liked to say, on the north side of thirty. She even had the same auburn hair and emerald eyes.

“Yes, that's Mrs. Andrews. She had twelve children before she died.”

Before Beatrice could say more, the front door flew open and in stomped an elderly gentleman. He was on the verge of a good, old-fashioned hissy fit.

“Y'all don't deserve a say in this wedding!” he said to a young woman who'd slunk in behind him.

The girl looked to be the right age for his daughter. She wore flip-flops and a wrinkled peasant blouse, and she buried her head in her hands. Well, that lifted the blouse an inch or two and exposed her bare stomach.

Lorda mercy

. It seemed the girl and her fiancé must have eaten supper before they said grace, as we said here in the South, because an unmistakable bump appeared under her top. She looked to be about four months along, give or take a few weeks, and I could see why her daddy wasn't too happy with her right about now.

. It seemed the girl and her fiancé must have eaten supper before they said grace, as we said here in the South, because an unmistakable bump appeared under her top. She looked to be about four months along, give or take a few weeks, and I could see why her daddy wasn't too happy with her right about now.

After a piece, she lifted her chin and glared at him. “I hate you!” Her voice rippled as cold as the river water that ran nearby. “I wish you were dead.” She stalked away.

I fully expected the man to cringe, or at least follow her. Instead, he merely glanced our way and shrugged. After a minute, he pivoted on the spectacle he'd caused and casually strolled away, leaving a bit of frost in the air.

“Oh, my. Why don't we continue?” Beatrice said.

Poor Beatrice

. She obviously wanted to divert our attention elsewhere. It couldn't have been every day one of her hotel guests wished another guest was dead. She hustled us farther into the ballroom, as if nothing had happened, all the while explaining the history of Morningside Plantation.

. She obviously wanted to divert our attention elsewhere. It couldn't have been every day one of her hotel guests wished another guest was dead. She hustled us farther into the ballroom, as if nothing had happened, all the while explaining the history of Morningside Plantation.

Turned out one of the grandest plantations in the South almost didn't make it through the Civil War. If it hadn't been for some Union soldiers who couldn't bear to see it destroyed, the mansion might have been shelled like its neighbors. All I could think of was hallelujah for chivalry and those cavalrymen's romantic natures.

“As I mentioned, the Andrewses had twelve children. One of them, Jeremiah, died in the war. Some of the maids swear they've seen a soldier patrolling the halls after dark.”

Now, I've read my share of stories about ghostsâmostly in the

National Enquirer

at the Food Faireâbut they always haunted musty graveyards or neglected attics and not elegant ballrooms painted pure gold. “But this place is much too pretty to be haunted.”

National Enquirer

at the Food Faireâbut they always haunted musty graveyards or neglected attics and not elegant ballrooms painted pure gold. “But this place is much too pretty to be haunted.”

“The house used to be a plantation with a bunkhouse for slaves. Think about it . . . there are probably hundreds of restless spirits here.”

First deceased Confederate soldiers and now wandering ghosts. It was all becoming a bit much. “We'll be sure and let you know if we have any visitors tonight. Won't we, Ambrose?”

Before my friend could reenter the conversation, though, someone else's cell rang.

“I'm sorry.” Beatrice reached into a pocket and pulled hers out. “Looks like it's the front desk. Do you mind if I let you explore this room on your own for a few minutes? It's not what we usually do, but this shouldn't take long.”

I covered my joy with a quick nod. “Of course not. We don't mind at all. Take your time. We'll be fine until you get back.”

She hustled away and quietly shut the door behind her.

Gracious light! If she believes we'll actually stay in one place, she is one brick shy of a load.

I quickly grabbed hold of Ambrose's arm. “C'mon, Bo. Follow me.” I counted to three and then opened the door and stepped into the hall. Ever since we'd walked through the front door, there was one other room I'd been dying to see. It'd called to me from the foyer. Only, I couldn't do much more than peek at it through the doorway until now. The coast was clear. I tiptoed down the hall with Ambrose in tow, until it appeared.

The dining room. Dripping in yellow paint with matching curtains, it looked like a pat of melted butter. A gleaming mahogany table had been set for fourteen with bone china, crystal stemware, and delicate bowls for washing one's fingers. Had a room ever looked so magnificent?

I pulled a mahogany chair away from the table and delicately perched on its silk cushion.

“Missy!” Ambrose frowned at me, though he probably wished he'd thought of it first.

“I'm not hurting anything.” Lord knows the chair had lasted more than a hundred and fifty years, and it surely would last another hundred or so whether I enjoyed it or not. It was meant to be sat on. But much as I hated to admit it, the carved chair-back did

not

feel good against my spine, and I rose again. “You wouldn't like it. Hard as nails.”

not

feel good against my spine, and I rose again. “You wouldn't like it. Hard as nails.”

I moved past the offending chair to a pair of windows. With elaborate gilt cornices and silk tassel tiebacks, they looked like something from an old-fashioned movie theater. Couldn't help but notice the picture-perfect May weather outside. Almost nice enough to compete with the gorgeousness inside.

I was about to mention it to Ambrose when something caught my ear. A low voice, quick with anger, its fierceness surprising. Whatever could someone possibly find to argue about in such a glorious place? The curtain sheers lifted easily enough and there was Beatrice, with her back to an azalea bush and her cell to her ear.

“I told you no.” For someone who was supposedly dealing with the front desk, she sounded awfully mad. “Don't call me until after the wedding. You know what you have to do.”

Ambrose quickly joined me by the window. “Well, well. What have we here?”

“Sounds like this place has more drama than wandering ghosts.” All I could think of was hallelujah . . . and pass the finger food.

Other books

Warprize by Elizabeth Vaughan

Master of Bella Terra by Christina Hollis

Bullettime by Nick Mamatas

The Vorbing by Stewart Stafford

The Accidental Time Traveller by Janis Mackay

Veiled Target (A Veilers Novel) by Robin Bielman

Breakwater Bay by Shelley Noble

Child of Fate by Jason Halstead

Saving the Beast by Lacey Thorn