Murder Rap: The Untold Story of the Biggie Smalls and Tupac Shakur Murder Investigations (24 page)

Read Murder Rap: The Untold Story of the Biggie Smalls and Tupac Shakur Murder Investigations Online

Authors: Greg Kading

There was little doubt that Sugar Bear was a dangerous individual. But what would make a difference in court would be our ability to establish not simply his personal history of mayhem, but rather his corporate criminal activities. Any RICO case depends entirely on proving an ongoing pattern of criminal activities. Murder, assault, robbery, extortion, fraud; any one of those charges could carry significant penalties when tried as separate counts. But such penalties expanded exponentially if they could be shown to be part of a continuing criminal venture. If we could prove that Death Row Records, for example, was funded, in whole or in part, by the sale of narcotics, we would have a viable RICO case and could put Suge away for a long time.

To that end, Daryn and I put a premium on reviving a relationship the federal task force had made with Michael “Harry O” Harris. One of the most successful crack dealers in the country, Harry O had used his ill-gotten gains to fund a range of successful legitimate businesses. Before age thirty he owned and operated a fleet of limousines, a Beverly Hills hair salon, a high-end auto dealership, a construction company, and a delicatessen. He also had his hand in a number of show business ventures, funding Rap-a-Lot Records, a Houston hip-hop label that was home to the hit Geto Boys, and producing two hit Broadway plays, one of which starred Denzel Washington at just the point when the young actor’s career was starting to take off.

In 1987, his empire came crashing down when he was convicted on attempted murder and drug charges and was sent to San Quentin to serve a twenty-eight-year sentence. But even behind bars, Harry O’s entrepreneurial flair was in evidence. He became editor of the

San Quentin News

, wrote a book of short stories on prison life, and, more to the point, continued to expand his investment portfolio, using drug funds he had hidden from government seizure. According to interviews he had given to the FBI during their Death Row investigation, Harry O had had more than twenty cell block visits from Suge Knight, and as a result of these discussions agreed to put $1.5 million into Knight’s proposed new rap start-up, Death Row Records. Shortly thereafter, Death Row’s megahit

The Chronic

was released and Suge signed a lucrative distribution deal with Interscope Records, cutting his incarcerated investor out of the profits in the process. “I was betrayed,” Harris claimed in an interview with the

Los Angeles Times

. “Michael Harris makes things up to try and get out of jail,” was Suge’s reply and it certainly came as no surprise that he would indignantly deny a partnership with the jailed drug dealer. If it could be proven that Death Row was launched with drug money, the linchpin of a criminal conspiracy case would be in place

It was with that in mind that Daryn and I paid a call on Harry O. Our hope was that we could pick up where the FBI had left off and try to nail down his claim that he had helped to finance Death Row with crack cocaine money. At six feet five, Harris was an imposing presence; pound for pound every bit the equal of Suge. He listened impassively as we made our case by suggesting that, in exchange for some hard facts on his investment deal, maybe we could be of assistance in his ongoing efforts to get out of prison.

But Harry O had something else in mind. He wanted us to investigate the 1998 drowning death of his brother, which he had good reason to believe was not an accident: David Harris was himself active in the drug trade and had been the target of two separate homicide investigations. Yet, as Daryn and I took a closer look at the death, it became clear that there had been no foul play. Not that we could convince Harry O of the fact. When we returned to San Quentin with the news, he dismissed us with a wave of his huge hand and walked out of the meeting. Our hope of eliciting his testimony to establish a RICO case against Suge had run aground. The enterprising inmate meanwhile returned to his primary activity: mounting a $107 million lawsuit against Suge Knight over Harris’s original Death Row investment. An eventual decision in his favor was, along with the $6 million IRS claim, a precipitating factor in Suge’s bankruptcy declaration.

As it would turn out, Suge’s bankruptcy provided us with another opportunity to build a plausible RICO case. As part of the disposal of his assets and distribution of the proceeds, the bankruptcy trustee examined what else might be in his possession aside from the eleven dollars that he claimed comprised his liquid assets. As a result, more than ten thousand Death Row recordings were inventoried and their value assessed.

It was shortly afterward that we were contacted by detectives from the Livingston County Sheriff’s Department in western Michigan, giving us a heads-up on an intriguing case that had developed in their jurisdiction. Carl “Butch” Smalls was a former Suge Knight associate who had worked at Death Row and nurtured musical ambitions of his own. His dreams of stardom eventually dashed, Smalls moved to Michigan where he lived with his girlfriend. Their often violent relationship culminated in an assault that prompted the battered girlfriend to move out. Gathering her belongings, she went to a storage facility the two had rented when they had first consolidated households. It was there that she discovered recording-studio hard drives and master tapes, their labels designating them as property of Death Row Records. Confronting Butch, she was told that he had been ordered by Suge Knight to hide the cache of music when Death Row was going under. She reported her discovery to the local authorities and, more to the point, to the bankruptcy court that was handling Suge’s Chapter 11 proceedings. Not long after, we were made aware of the find.

The link to our investigation was obvious. Suge had sworn in bankruptcy court that Death Row’s assets had been duly disclosed. Yet here was a substantial hoard of recordings that not only had not been declared, but had been deliberately concealed from authorities. Jeff Bennett and I flew to Detroit, immediately seized the contents of the storage space, and had them shipped back to Los Angeles for examination. Scrutinized by the bankruptcy trustees, it was determined that the tapes and digital masters contained more than a thousand previously unreleased songs from some of Death Row’s top artists, including a half dozen unheard Tupac Shakur originals. The estimated value of the music: $20 million. Apprised of our find, Assistant U.S. Attorney Tim Searight immediately added bankruptcy fraud to the growing catalog of Suge Knight’s possible RICO violations.

Bankruptcy; the wholesale death or defection of his artists; the total collapse of his record label: none of it seemed to convince Suge that he wasn’t still a major music-business player, whether anyone else thought so. In early 2008, Suge accordingly arrived at the front gate of the famed producer and executive Jimmy Iovine’s estate. Chauffeuring him for the occasion was an Eight-Seven Crip who at the time was also an at-large parolee considered armed and dangerous. Summoning the security guard through an intercom, Suge announced that he had come to party with his old friend Jimmy.

Iovine had, in fact, once been tight with Suge, back when Knight had first signed the distribution deal with Interscope Records, at a time when they both needed a change of fortune. The Brooklyn-born Iovine had begun his career as a recording engineer, working with the likes of John Lennon and Bruce Springsteen before becoming one of the hottest producers of the eighties. In 1990 he formed the independent Interscope Records, but the start-up sputtered and was about to go under when Iovine induced Suge to bring Death Row Records under his label’s umbrella. It was a canny move, considering the impending gangsta rap phenomenon, which Iovine did much to promote and popularize. Success bonded the ambitious pair until Suge’s increasingly erratic behavior became too much for Iovine to tolerate. In 1997, the two parted ways, but not before Iovine poached some of Suge’s biggest-selling artists, including Snoop Dogg. In early 2008, Snoop released

Ego Trippin’

on Interscope. It was in celebration of the album’s first single that Iovine had thrown a party that night.

There was only one problem: the event wasn’t being held at Iovine’s home. In fact, Iovine wasn’t on the premises, having earlier left for the party. Informed of that fact by security personnel, Suge and his escort proceeded to cruise the perimeter of the property, all the while being watched on closed-circuit cameras from inside the guard shack. When they pulled up next to the service entrance, a pack of German shepherds was released, chasing the intruders away. The next morning, a disturbed Jimmy Iovine contacted Chief William Bratton directly. Daryn and I, along with Bill Holcomb, were dispatched to interview the record executive, and it was clear from the beginning that he had been rattled by Knight’s sudden appearance. He hadn’t had contact with Suge for years, Iovine explained, and considered his sudden appearance as a thinly veiled threat, either in retaliation for the Snoop Dogg signing or to extort money from his old business associate. He wanted it dealt with right away, but for the moment all we could do was file away the complaint in Suge’s growing dossier of potentially indictable crimes.

But we wouldn’t get a real break in our efforts to put Suge behind bars until we focused our attention on a possible extortion and fraud case. It was, at that time, the first new incident of Knight’s criminal activity that we had uncovered on our own, which meant that witness recollection would be a lot fresher than some of the decade-old allegations we were trying to resurrect.

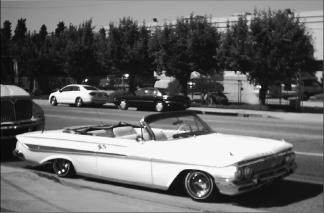

Among the many uncanny aspects of the Tupac and Biggie murder investigations, was the way in which certain clues kept reappearing and repeating, mirroring the same startling similarities. So it was with a vintage Chevrolet Impala. The make of vehicle had first appeared as the drive-by car outside the Petersen. Now, another Impala was about to become one of our most important pieces of evidence against Suge Knight.

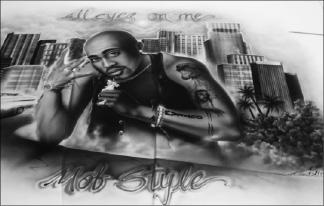

In 1996, Knight had hired an auto restorer named Juventino Yanez. According to a 1999 DEA report, Yanez was a “well known cocaine distributor, believed to be distributing as many as fifty kilograms of cocaine per week,” out of his auto shop. But Suge’s deal with Juventino actually involved legitimate restoration. For a cool $30,000, he was hired to bring a vintage 1961 Impala back to its pristine showroom condition. The car was to be presented to Tupac with an airbrushed rendering of the cover art for his forthcoming

All Eyez on Me

album splashed across the deck. But Tupac never had a chance to enjoy the lavish gift. Just prior to its completion, he was gunned down in Las Vegas.

After the murder of its intended owner, the Impala passed through many owners, beginning with Tupac’s mother, Afeni, who was reputedly given the car by Suge in memory of her son. But it was Yanez who retained the vehicle’s pink slip, even after he lost possession of the car itself. The Impala, in fact, traded hands a number of times before ending up in the possession of Armando Hermosillo, owner of an El Monte body shop. Hermosillo had bought the car, without the pink slip, for $15,000, and after obtaining a duplicate title he proudly put it on display in the street outside his business to attract customers. It was there, in the late summer of 2006, that the Impala was spotted by Yanez’s son, who returned the next day with his father. “I built that car for Suge Knight,” Yanez told the body shop owner, insisting that the Impala was rightfully his because, as he put it, “I pulled a lot of time for those guys.” The time to which he referred was a prison sentence Yanez served after police discovered a cache of guns hidden in his garage.

Hermosillo was not impressed and Yanez left without the Impala. A few weeks later Yanez’s son returned to the body shop, this time in the company of a contingent of Bloods. Once again Armando held his ground, until he was handed a cell phone. On the other end: Suge Knight. “That car belongs to the industry,” Suge informed the body shop owner. “Give it over. I have my own cops. I’ll call them. You know what I can do to you.” Hermosillo stepped aside as the vehicle was loaded on a flatbed tow truck and driven away.

But the saga of the ’61 Impala with the Tupac paint job didn’t end there. A few weeks later a friend and fellow officer who worked for the Bell Gardens Police Department, and happened to be the brother-in-law of Armando Hermosillo, contacted me. It was clear from what he told me that we had the makings of a possible extortion case, based on Suge’s none-too-subtle threat to call out his own enforcers if Hermosillo didn’t cooperate. The Impala had provided us with a very lucky break, if we could back up Hermosillo’s account of the fear and intimidation Suge had employed to gain possession of the car.