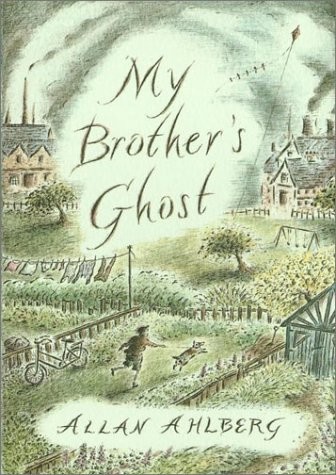

My Brother's Ghost

My Brother's Ghost

ALLAN AHLBERG

PUFFIN BOOKS

PUFFIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi –110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published by Viking 2000

Published in Puffin Books 2001

10

Copyright © Allan Ahlberg, 2000

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-192806-7

For Jessica

Contents

1 The Funeral

2 Looking for Tom

3 Rufus

4 Bad Times

5 The Fight

6 Remembering

7 Canada

8 Ghost Talk

9 The Thief

10 Important Things

11 Running Away

12 Drowning

13 The Hospital

14 Getting Better

15 Tom's Compass

16 Leaving

What I am about to tell you is true, well, as true as I can make it. (These things happened forty years ago.) Nothing is made up. Where I could not remember the details, I have left them out.

My name is Frances Fogarty. I am the middle child, the sister, in the story. Tom was my brother. Harry was, and happily still is, my brother. Marge was my aunt, Rufus my dog, Rosalind my enemy. And so on

.

You won't, I don't suppose, believe in ghosts. That can't be helped. The truth is, in a curious way I'm not sure I do either. Ghosts? I cannot speak for ghosts in general, numbers of ghosts. No… just the one

.

The Funeral

H

E WAS TEN WHEN

it happened, and I was nine and Harry was three. Running out into the street after Rufus, he was hit by nothing more than a silent, gliding milk-float. His head cracked down against the pavement edge. A fleck of blood rose up between his lips. His legs shook briefly, one heel rattling like a drumstick against the side of the float. And then he died.

My brother, my clever, understanding older brother. My best friend and biggest pest of course sometimes. The sharer of my secrets, the buffer between me and Harry. Dead.

The milkman I remember was in tears, smashed bottles at his feet, milk running in the gutter. I had hold of Harry's hand. Rufus, all unconcerned, was still prancing about.

Four days later, the funeral. A pair of black cars, men in black suits, flowers and wreaths, the vicar. Harry and I were there. Uncle Stan said we should stay home. Auntie Marge said we should go. So we went.

It was a morning funeral. The grass in the cemetery was still wet with dew. The vicar spoke and the coffin was lowered on ropes into the ground. I remember then a train went by – invisibly in the cutting – the hiss and rattle of it, steam rising.

Who else was there besides us and Uncle Stan and Auntie Marge? The vicar, I've mentioned him. The undertaker's men. The grave diggers waiting at a distance. A neighbour, a friend of Auntie Marge’s, had come I think, and the woman who ran the Cubs. The milkman too, perhaps. Somebody from the school.

And it was cold, I remember that, the low November sunlight glittering on the wet headstones. There was the sound of traffic from the road, the rumble of the presses in the nearby Creda factory.

It was Harry who saw him first. He grabbed my sleeve but said nothing. I looked… and there was Tom. He had his hands in his pockets, his jacket collar up. His hair was as uncombed, as wild as ever. And he was leaning against a tree.

Looking for Tom

W

E'D HAD OUR SHARE

of troubles when Tom was alive. They did not go away after he died. Auntie Marge was softer with us for a day or two following the funeral. A bit of extra cake at teatime; a couple of comics at the weekend; now and then asking us how we were. But Harry was still wetting the bed, and soon she was yelling at him again as loud as ever and slapping the backs of his little legs. And I was yelling at her and getting clouted too. And Uncle Stan was sloping off embarrassed to his shed. Things were back to normal.

Except of course for Tom.

We

had

seen him. At least Harry and I had. As we left the cemetery we had walked right past the tree where he was leaning. It was his face as clear as day. He looked at us, frowning, puzzled perhaps, as though our presence was a surprise to

him

. A little later, as the car drove away at a snail's pace, I saw him again, standing beside the grave. The grave diggers had removed the carpets of artificial grass, the platform of planks, and were shovelling the soil back into the hole. Tom was watching them.

School was hateful to me. I couldn't join in with things because of my leg. (Polio, I wore a caliper.) My teacher, Mrs Harris, said I was a scowler. (I was!) Rosalind and her gang were much of the time unfriendly, or worse. All the same, the day after the funeral I was back, only this time with no Tom to walk with or look out for me in the playground. Again, just as with Auntie Marge, there was a day or two of sympathetic smiles and considerate voices – Maureen Copper even shared her liquorice with me – before things got back to normal.

On Saturday I went looking for Tom. I had some errands to do for Auntie Marge in the morning. There was a steady drizzling rain in the early afternoon. So it was nearly four o'clock when I left the house. Rufus was with me, my excuse for going out.

The cemetery was divided into two parts, with a road, Cemetery Road, passing between them. I stood at the gates just after four. More rain was threatening. Already the street lights were beginning to glow. Rufus tugged us in. There was a light shining out from the side door of the chapel, I remember. Three or four people with flowers and cans of water were moving about. There was a smell of chrysanthemums.

What must I have been thinking then, as I stepped off down the path? I was only nine, after all. The cemetery was a place of morbid fears and dread. A place you avoided. A place you

ran

past (if you could).

Tom. I was thinking of Tom. I was scared and thinking of Tom. Holding Rufus close in on his lead for comfort and looking for Tom. Tom was here. He was here.

How

was he here?

The tree first, dripping noisily on its own dead leaves. No Tom. Then the grave: a mound of earth – drenched wreaths and flowers – smudgy, unreadable messages on little cards – muddy footprints in the grass. No Tom.

It was drizzling again now. My leg had begun to ache, the cold metal of the caliper chafing against my knee. Rufus was kicking his back legs in the loose soil. I turned and came away.

On Cemetery Road the street lights shone in the damp air, smudgily, like the blurry messages on the little cards. The air itself had a yellow, sulphurous tinge. (There were more coal fires and factory chimneys in those days.) A fog was beginning to form.

At the end of our street I let Rufus off his lead. He liked to run, to

hurtle

really, home from there. I limped on up to the house. On the low wall at the front enclosing a tiny patch of garden, Tom was sitting. His face still had that puzzled frowning look. His collar was still up.

I stood, my hair soaking wet and flat against my head, drops of water on my nose and ears and chin. Tom's mouth was open. He was speaking or trying to, it seemed. There was no sound, as though a sheet of glass was placed between us. He made a gesture with his hand, a wave perhaps. There was a sharp tapping at the window. Auntie Marge was scowling at me, she was a scowler too. She wondered at me standing so still in the rain, wanted me in for my tea.

Tom watched me as I limped off down the entry.

His

hair, I just had time to notice, was bone dry.