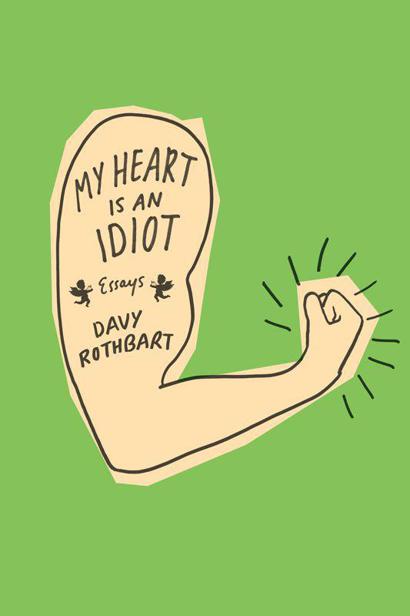

My Heart Is an Idiot: Essays

Read My Heart Is an Idiot: Essays Online

Authors: Davy Rothbart

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

for the townies

I’ve come to feel out on the sea

These urgent lives press against me.

I’m way too deep into the weird life

Broken bottles and a butterfly knife.

Sometimes I hear that song, and I’ll start to sing along And think, Man, I’d love to see that girl again …

CONTENTS

NINETY-NINE BOTTLES OF PEE ON THE WALL

THE STRONGEST MAN IN THE WORLD

When I was a kid, I had a friend down the street named Kwame whose older brother was mentally handicapped. This gave Kwame license, he felt, to make fun of other mentally handicapped folks he encountered. If anyone gave him grief for it, he’d say, “Hey, I’m just playin’ around—my

brother

’s a retard.” Kwame used to dropkick retard jokes right in his brother’s face. “He’s my brother, I’m allowed to fuck with him,” he’d always explain. Of course, if anyone else unleashed the same kind of jokes, they’d get their ass beat quick.

It must’ve been some adjacent line of reasoning that induced me, growing up, to make fun of my mom for being deaf. She’d lost her hearing through a mysterious illness three years before I was born, and I grew up speaking sign language with her. I picked it up easily, like any kid in a bilingual household, watching my dad and my older brother speak to her in sign. My first word, I’ve been told, was the middle finger.

I took advantage of my mom’s deafness in small ways at first. In the car, she’d be driving, and trying to lecture me about something, but I’d have the radio cranked so loud I couldn’t hear her. As long as I kept the bass down, how was she to know that I was nodding along to the Fresh Prince song “I Think I Can Beat Mike Tyson” and not to her instructions on how to clean out the gutters? She never understood the looks she got from other drivers, who must have been baffled to see a middle-aged mom tooling slowly along in an Aerostar, blasting Def Leppard at rock-concert volume. Funniest, to me, was the time we pulled up alongside a cop and I slipped in my N.W.A tape from the glove box, cued to the song “Fuck tha Police.”

Then there were the stunts I pulled in grade school to impress the kids in my neighborhood. My mom would be washing dishes, her back turned to the kitchen, and I’d sneak up behind her, a few kids in tow, and yell at the top of my lungs, “Hey,

BITCH!!

Hey, you fuckin’

BITCH!!

” Then we’d all run, laughing and screaming, out of the room. The whole show lasted ten seconds, but I could’ve sold admission. Kids I’d never even met from a mile down the road used to knock on our door, heads hung low, talking softly as though they’d come to buy switchblades or porno mags. “Can we see you do the thing where you yell ‘Bitch!’ at your mom?” they’d say. After I obliged, I’d always invite them to try it themselves, but not even the bravest of them could muster the courage. “That’d just be so

wrong

,” they’d say. “That’d be like calling Kwame’s brother a retard.”

Our house had an unusual feature—a doorbell in the dining room. The room had originally been a screened porch attached to the back of the house, but the previous owners had filled in the walls and added windows to create a one-room addition. What had once been a doorbell at the back door was now a doorbell in the middle of the house—painted over, so my mom had never noticed it. Our family dog, Prince, was trained to fetch my mom anytime someone came to the front door and knocked or rang the doorbell. To the wild entertainment of my brothers and me, we discovered that if we rang the doorbell in the dining room, Prince would start barking furiously and tug my mom by her sleeve to the front door. It was Ding-Dong Ditch from the comfort of our own house! Even my dad got in on the action. We’d watch with barely suppressed glee as my mom opened the door and peeked outside, only to be greeted by an empty front porch. “But there’s nobody here,” she’d say to Prince, with a confused twinge in her voice. On nights we played the game a bunch of times—okay, most nights—she thought the house was under siege by ghosts. She’d sometimes stand there for a full minute, staring out into the misty dark.

*

One day halfway through sixth grade, I got into major trouble at school. The music teacher, Mrs. Machida, kept getting upset at me for horsing around with my friends during class. Finally, she ordered me to report to the principal’s office. I said, “Okay, fine—you fuckin’

BITCH!

” Wow, who could’ve known she’d turn magenta and haul me out of the room by the scruff of my neck? I’d grown cavalier with curse words, having called my mom the same thing a thousand times without a flinch.

“We’re calling your parents,” said the principal, Dr. Joan Burke, searing me with her death stare after Mrs. Machida told the story. I explained to them that my dad was at work and that my mom was deaf. Back then, my mom had no operator-assisted phone—that advance in technology was still years away. When she wanted to make a phone call, whether it was to order a pizza or talk to a friend for an hour, she needed me or one of my brothers to translate for her. “Look,” I said to Mrs. Machida and Dr. Burke. “You guys want to talk to my mom, you got to wait till I get home so I can tell her what you’re saying.”

Tell her what you’re saying

. I thought about it the whole bus ride home, not sure what exactly I was about to do, but sure I was about to do it. The phone was ringing as I walked in the door.

“Hello?”

“Davy? It’s Dr. Burke. Can you put your mother on, please?”

I tracked down my mom and told her the principal of my school was on the phone. “What does she want?” my mom asked me.

I shrugged and flashed a mystified look.

My mom picked up the receiver. “Hello, this is Barbara,” she said. She passed it back to me.

Dr. Burke said, “Okay, Davy, you need to tell your mom that there’s a serious situation based on your behavior in Mrs. Machida’s class today. Does she already know about what happened?”

“Um, naw.”

“You need to tell her there’s a serious situation we need to discuss with her. Your situation. That

language

was used. Unacceptable language. And that if this kind of behavior occurs again, there will be serious consequences. Suspension or expulsion.”

“Okay,” I said. “Hold on. Let me tell her all that.”

I held the phone low and started signing to my mom, keeping my voice at a whisper so she could still read my lips without Dr. Burke hearing me. “Dr. Burke wants you to know about something that happened today at school.” I paused. “It was … during recess. Some kids, they … they were torturing a butterfly. They were pulling its wings off. And I jumped in the middle of them and I saved the butterfly.” Who knows where this shit was coming from? A dream? A demented episode of

3-2-1 Contact

? “The butterfly…” I went on, “… it was pink. It was from Madagascar. It was the music teacher’s pet, Mrs. Machida. She told Dr. Burke, and Dr. Burke thought you should know. But she has to go, she’s really late for her dentist’s appointment. It’s a super-important dentist’s appointment.” I said to Dr. Burke, “Okay, here’s my mom,” and passed the phone back to her, praying for the best. But after faithfully translating thousands of calls for her, how could she have guessed that the train had finally jumped the tracks?

“That’s a

wonderful

story,” my mom said. “Thank you very much for your call. And please thank the music teacher for passing word along. Take care now. Here’s Davy.” She handed the phone back to me.

“See you tomorrow, Dr. Burke,” I said quickly.

“Wait, what did your mom say about ‘wonderful’?”

“She was being sarcastic. I’m in for the whupping of my life.”

I hung up in a hurry, my heart booming. The narrow escape should’ve taught me a lesson. That should’ve been it—one and done—the kind of trick you retire immediately, and count your blessings for. But it wasn’t. It was more like winning big on your first visit to a casino. It was a gateway drug. It was a call to arms. It was an awakening.

I realized, in the days and weeks that followed, that helping my mom with phone calls, which had always been a burdensome chore, could be more like a

Choose Your Own Adventure

book. My mom’s friends—weirdly, perhaps, to her—began to make odd suggestions, like that she take my brothers and me to Cedar Point, the amusement park, or that she rent Eddie Murphy’s

Delirious.

My dad, calling home before he left work, often requested that my mom pick up a bag of Soft Batch chocolate chip cookies from the store. Anytime an exchange grew dicey, I’d tell my mom that the person on the other end of the line suddenly had to go. “That’s so bizarre,” my mom said one night after a call had ended abruptly. “Who schedules a dentist appointment at eight p.m. on a Sunday?”

Then, when summer hit, it occurred to me that crossing the wires on my translations was Grapefruit League ball. The truth was, I didn’t need a real person on the other end of the line. One afternoon I asked my mom if I could go to my friend Mike Kozura’s house to spend the night with a bunch of other friends, and she said no way—Mike lived alone with his dad, and she knew his dad was out of town for two weeks. Protesting her verdict would’ve been useless, so a couple of hours later, I gave my new tactics a trial run. I was helping my mom mop up some backed-up drain water in the basement, when, out of the blue, I dropped the mop and dashed upstairs, as though the phone was ringing. I took the receiver off the hook and went back down to get her. I told her that my friend Donald Chin’s mom was on the line. “She wants to talk to you,” I said.

We clomped upstairs, and while the phone started to bark that angry buzz that comes from leaving it off the hook too long, my mom said hello to Mrs. Chin, then passed the phone back to me. For a half minute I nodded my head, pretending to listen, saying things like, “Cool!” “I understand,” “Thanks so much,” and “That sounds great,” and at last explained to my mom that Mrs. Chin wanted her to know that she’d agreed to stay the night at Mike’s house to chaperone the party. Mrs. Chin, I told her, had offered to host the sleepover at her house, but some of the kids were afraid of their pet python and boa constrictor. The Chins really had these snakes; my mom had seen them. It had taken me all afternoon to conjure up just the right vivid, walloping fact that would blot out the fictions in its shadow. I handed my mom the phone and she spoke into it, already sold hook, line, and sinker. “Thank you so much,” she said, as the phone kept buzzing. “I really appreciate that. You know, I’d invite all the boys over here, but the basement’s all flooded and the house is a complete mess.” An unexpected low, sinking feeling overcame me as my mom went on, chatting up Mrs. Chin about her other kids, the Chins’ family restaurant, and some local school board brouhaha. I felt like Oppenheimer, both thrilled by and afraid of the awesome power of my new, terrible weapon.