My Life So Far (7 page)

The first Fonda to cross the ocean was Jellis Douw, a member of the Dutch Reform Church, who came to the New World in the mid-1600s, fleeing religious persecution. He canoed up the Mohawk River and stopped at an Indian village called Caughnawaga in the middle of Mohawk Indian territory. Within a few generations after my Dutch-Italian ancestors arrived in the Mohawk Valley, there were no more Indians—the town became known as Fonda, New York.

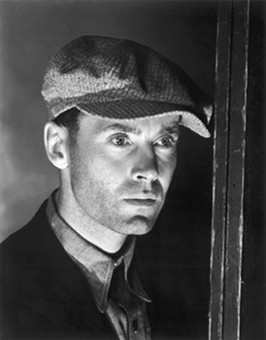

Dad as Tom Joad.

(Photofest)

It is still there, not far from Albany. You get to it by riding north along the Hudson River for a while and then west, a train ride I took from Grand Central Terminal for six years—while attending the Emma Willard boarding school in Troy, New York, and then Vassar College in Poughkeepsie.

Tina Fonda, Troy, and me in Fonda, New York, by the graves of our namesakes.

(Montgomery County Department of History & Archives)

The last Fonda family reunion, in Denver. Dad is fourth from left in the front row next to Shirlee, then Aunt Harriet and her daughter Prudence. Back row, left to right: Peter, Amy, Becky, Bridget, and a cousin, Lisa Walker Duke.

In the seventies, I visited the town of Fonda with my children and my cousin Tina, daughter of Douw Fonda, direct descendant of the original Jellis Douw. We spent most of our time in the town’s graveyard, where, on lichen-covered gravestones, some almost toppled over, we could read the old Italian name Fonda, preceded by Dutch names such as Pieter, Ten Eyck, and Douw. But there, among them, was a Henry and a Jayne—our long-dead namesakes.

Mother’s ancestors were Tories, loyal to the British. The Fondas were staunch Whigs who actively supported the colonial cause. After the Civil War, Ten Eyck Fonda, my great-grandfather from Fonda, New York, brought the Fondas to Omaha, Nebraska, where my father was raised. Ten Eyck went there as a telegrapher with the railroad, a skill he’d gained in the army. Omaha at that time was a hub of the new railway network.

I never knew my father’s parents, who died before I was born. William Brace Fonda, my grandfather, ran a printing plant in Omaha, and my grandmother Herberta, whom I apparently favor, was a housewife who raised three children—my dad and his sisters, Harriet and Jayne. Dad’s parents and many of their relatives were Christian Scientists, Readers, and Practitioners. If one can judge from the photos, they were a close, happy, smiling family.

I have often pored over shoeboxes full of family memorabilia looking for clues to my father’s dark moods. I am not alone in this quest. Several years ago, when it became clear that Dad’s remaining sister, Aunt Harriet, hadn’t long to live, I went to visit her at her home outside of Phoenix to ask my questions.

“Was Dad close to his mother? Were there problems in the family?”

“No, absolutely not!” she answered. “And I just don’t understand all you girls coming down here to look at the pictures and ask me questions about our family!”

This took me by surprise. “What do you mean, Aunt Harriet? Who else has come?”

Aunt Harriet named various cousins and their daughters. Ah-ha, thought I. Perhaps the Fonda malaise has crept into other corners of the family. Now, it seemed, some of the younger generation were seeking answers, too.

M

y visit with Aunt Harriet served to remind me how little the people of my father’s generation were accustomed to introspection. Her memory held no nuances, no shades of gray. As far as she was concerned, theirs had been an idyllic life, and perhaps it had been.

I knew that my father had great admiration for his father, William Brace Fonda—like him, a man of few words. There are two stories my father told, and they are revealing.

One evening after dinner, William Brace drove his son down to the printing plant. From a second-story window, he had Dad look down onto the courthouse square below, where a crowd of shouting men brandished burning torches, clubs, and guns. Inside the courthouse, in a temporary jail, a young black man was being held for alleged rape. There had been no trial, not even any charges filed. The mayor and sheriff were there on horseback trying to quiet the mob. Eventually the man was brought out into the square and, in the presence of the mayor and sheriff, hanged from a lamppost. Then the mob riddled his body with bullets.

Fourteen years old, Dad watched all this in shock and terror. His father never said a word—not then, not on the drive home, not ever. Silence. The experience would forever be a part of my father’s psyche. It played itself out in his

12 Angry Men,

in

The Ox-Bow Incident, Young Mr. Lincoln,

and

Clarence Darrow,

and in unspoken words that I heard plainly throughout my life: Racism and injustice are evil and must not be tolerated.

The second story has to do with his father’s attitude about acting. Dad had a $30-a-week job as a clerk at the Retail Credit Company in Omaha, but Marlon Brando’s mother, a friend of my grandmother’s, got him involved with the Omaha Community Playhouse, where Dad was offered the part of Merton in the play

Merton of the Movies.

When Dad began talking about acting as a career, his father said it was not appropriate for his son to earn his living in “some make-believe world” when there were good steady jobs available like the one he had. Dad argued, and his father refused to speak to him

—for six weeks.

Still, the play opened with Dad as Merton. And the whole family, including his father, went to see it. When Dad got home after the show, the family was sitting around the living room. His father had his face buried in a newspaper and still had not spoken to Dad. The mother and sisters began a very complimentary discussion of Dad’s performance, but at one point his sister Harriet mentioned something she thought he could have done differently. Suddenly, from across the room his father lowered his newspaper and said to her, “Shut up. He was perfect!”

Dad said that was the best review he ever got, and every time he told the story tears would well in his eyes.

These are among the very few clues I have about my father. I think that the repressed, withholding nature of his early environment colluded with a biological vulnerability to depression to make Dad the brooding, remote, sometimes frightening figure he became. I was stunned to discover in talks with my cousins that undiagnosed depression ran in the Fonda family. Dad’s cousin Douw suffered from it, and I suspect Dad’s father did as well.

Dad was a study in contradictions. Author John Steinbeck wrote this about him:

My impressions of Hank are of a man reaching but unreachable, gentle but capable of sudden wild and dangerous violence, sharply critical of others but equally self-critical, caged and fighting the bars but timid of the light, viciously opposed to external restraint, imposing an iron slavery on himself. His face is a picture of opposites in conflict.

Dad could spend hours stitching a needlepoint pattern he had designed or doing macramé baskets. He painted beautifully, and there was a softness in many of his acting performances, with nary a trace of the macho ethic. But to me, Dad was not a gentle person. He could be gentle with people he didn’t know, utter strangers. Often I run into people who describe finding themselves sitting next to him on transatlantic flights and go on about what an open person he was, how they drank and talked with him “for eight hours nonstop.” It makes me angry.

I

never talked to him for thirty minutes nonstop! But I have learned that it is not unusual for otherwise closed-off men to reveal a softer side of themselves in the company of total strangers, or with animals or their gardens or other hobbies. In the confines of our home, Dad’s darker side would emerge. We, his intimates, lived in constant awareness of the minefield we had to tread so as not to trigger his rage. This environment of perpetual tension sent me a message that danger lies in intimacy, that far away is where it is safe.

I

n his early twenties, and with his father’s permission, Dad hitched a ride to Cape Cod with a family friend and soon hooked up with the University Players, a summer stock repertory company in Falmouth, Massachusetts. Among them was Joshua Logan, one of my future godfathers. Dad was the only non–Ivy Leaguer among them.

When Margaret Sullavan, a petite, talented, flirtatious, temperamental, Scarlett O’Hara–style southern belle from Virginia, was invited to join the University Players the following summer in Falmouth, she stole his shy Nebraska heart. Their romance bloomed, until Sullavan went off to star in a Broadway play.

They carried on what was reported to be a fiery, argumentative courtship. After a year and a half, Dad proposed, she accepted, and they married and moved into a flat in Greenwich Village. Less than four months later it was all over. Dad moved into a cockroach-infested hotel on Forty-second Street, and Sullavan took up with the Broadway producer Jed Harris. Dad would stand outside her apartment building at night looking up at her window, knowing Harris was inside with her. “That just destroyed me,” he said a lifetime later to Howard Teichmann. “Never in my life have I felt so betrayed, so rejected, so alone.”

After the breakup, Dad describes going into a Christian Science Reading Room and finding a man to whom he bared his soul. “I don’t know what it was,” he said to Teichmann. “I must have had faith that day. I don’t even know who the man was, but he helped me to leave my pain in the little reading room. When I went out, I was Henry Fonda again. An unemployed actor but a man.” Oh yes, Dad, I want to cry out when I read that, but why didn’t you let that experience teach you that talking to someone who listens with an understanding ear can be healing, not a sign of weakness. If faith brought you a sort of miracle on that one day, why didn’t you allow yourself to be more open to it and why did you scorn us—Peter and me—each time we turned to these supports—therapy or faith—for help in our own lives?

Dad apparently withdrew into himself after that, working odd jobs here and there. A lot of people, including Dad, didn’t have enough to eat. For a while he shared a two-room apartment on the West Side with Josh Logan, Jimmy Stewart, and radio actor Myron McCormick. The four of them lived on rice and applejack. The other tenants in the building were prostitutes, and two doors down the notorious Legs Diamond had his headquarters.

While my mother, the woman who would become his second wife, was living in splendor as Mrs. Brokaw, in a mansion with a moat on Fifth Avenue, Dad was barely hanging on.

In 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was inaugurated president, and within a year Dad got his first big break, doing funny skits in the Broadway review

New Faces

with Imogene Coca. His reviews were terrific and his career started to take off. Around that time, Leland Hayward, who was on the brink of becoming the top talent agent in the country, signed him up and convinced a reluctant Fonda to go to Hollywood for $1,000 a week. He was on his way.