My Secret Diary (4 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

We did some mad projects together. For the first

two years at Coombe we did a combined history

and geography lesson called 'social studies'. We

learned all about prehistoric times, and made a

plasticine and lolly-stick model of an early stilt

village. We also started to write a long poem about

a caveman family. We thought up our first line –

Many millions of years ago

– but then got stuck.

We couldn't think of a rhyme for

ago

, so Chris

looked up the word in Jan's rhyming dictionary.

We ended up with:

Many millions of years ago

Lived a woman who was a virago.

perhaps the worst rhyme in many millions of years.

Mostly we simply played games like Chinese

Chequers, Can You Go?, and Beetle, and made

useless items with Scoubidou.

I loved Chris's bedroom, though it was very

small and she didn't have anywhere near as many

books as me. She had a little stable of china horse

ornaments, big and small, because she longed

passionately to go horse-riding, and saved up all

her pocket money and birthday money for lessons.

Her only other ornaments were plaster-cast Disney

replicas of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. A

few childhood teddies drooped limply on a chair,

balding and button-eyed. Her clothes were mostly

more childish than mine, though I hankered after

her kingfisher-blue coat, a colour Biddy labelled

vulgar – goodness knows why.

Chris's bedroom felt

safe

. You could curl up

under her pink candlewick bedspread, read an old

Blyton mystery book, and feel at peace. You

wouldn't fall asleep and dream of mad men walking

out of your wardrobe or monsters wriggling up

from under your bed. You wouldn't wake to the

sound of angry voices, shouts and sobbing. You

would sleep until the old Noddy alarm clock rang

and you could totter along to the bathroom in your

winceyette pyjamas, the cat rubbing itself against

your legs.

I'd slept at Chris's house several times, I'd been

to lunch with her, I'd been to tea, I'd been on

outings in their family car to Eastbourne, I'd been

to Chris's birthday party, a cosy all-girls affair

where we played old-fashioned games like Squeak

Piggy Squeak and Murder in the Dark.

It was way past time to invite Chris back

to my flat at Cumberland House. So Chris came

one day after school and met Biddy and Harry.

My home was so different from hers. Chris was

very kind and a naturally polite girl. She said

'Thank you for having me' with seeming

enthusiasm when she went home. I wonder what

she

really

thought.

Maybe she liked it that there was no one in our

flat to welcome us after school. It was fun having

the freedom of the whole place, great to snack on

as many chocolate biscuits as we wanted. When

Biddy came home from work she cooked our tea:

bacon and sausage and lots of chips, and served a

whole plate of cakes for our pudding – sugary jam

doughnuts, cream éclairs, meringues. Biddy

considered this special-treat food and Chris nibbled

her cakes appreciatively – but all that fatty food

was much too rich for her sensitive stomach. She

had to dash to the lavatory afterwards and was sick

as discreetly as possible, so as not to offend Biddy.

When Harry came home from work he was in a

mood. He didn't call Chris Buttercup, he didn't say

anything at all to her, just hid himself behind the

Sporting Life

.

Chris came on a sleepover once, and thank

goodness everything went well. It was just like

having a sister: getting ready for bed together and

then whispering and giggling long into the night.

We weren't woken by any rows, we slept peacefully

cuddled up until the morning.'

However, Biddy and Harry couldn't always put

on an amicable act. I remember when we got our

first car, a second-hand white Ford Anglia. Biddy

learned to drive and, surprisingly, passed her test

before Harry. We decided to go on a trip to Brighton

in our new car, and as a very special treat Chris

was invited along too.

We sat in the back. I was dosed up with Quells,

strong travel pills, so that I wouldn't be sick. They

made me feel very dozy, but there was no danger

of nodding off on

this

journey. Biddy and Harry

were both tense about the outing and sniped at

each other right from the start.

'Watch that lorry! For Christ's sake, do you want

to get us all killed?' Harry hissed.

'Don't you use that tone of voice to me! And it

was

his

fault, he was in the wrong ruddy lane,' said

Biddy, her knuckles white on the steering wheel.

'

You're

in the wrong lane, you silly cow, if we're

going to turn off at the Drift Bridge.'

'Who's driving this car, you or me? Ah,

I'm

driving because I'm the one who's passed the test!'

They chuntered on while I sat in the back with

Chris, my tummy churning. I talked frantically,

nattering about school and homework to try to

distract her from my angry parents. I madly hoped

she wouldn't even hear what they were saying.

She talked back to me, valiantly keeping up

the pretence, though she was very pale under

her freckles.

Biddy and Harry had gone past the stage of being

aware of us. We were stuck in a traffic jam going

up Reigate Hill. The car started to overheat, as if

reacting to its passengers. Biddy had to pull over

and open the bonnet so the engine could cool down.

'It's your fault, you're driving like a maniac. You

do realize you're ruining the car!' Harry said.

'If you don't like the way I drive, then

you

blooming well have a go,' said Biddy, bursting into

tears.

'Oh yes, turn on the waterworks,' said Harry.

'Just shut up, will you? I'm sick of this,' Biddy

sobbed. She opened her door and stumbled into the

road. She ran off while we stared.

'That's so typical! Well,

I

can't ruddy well drive,

as she's all too well aware,' said Harry – and

he

got out of the car, slammed the door with all his

strength, and marched off in the opposite direction.

Chris and I sat petrified in the back of the car,

our mouths open. Cars kept hooting as they

swerved around us. I reached out for Chris's hand

and she squeezed mine tight.

'You won't tell anyone at school?' I whispered.

'No, I promise,' she said. She paused. 'Jac, what

if . . . what if they don't come back?'

I was wondering that myself. I couldn't drive,

Chris couldn't drive. How would we ever get home?

I thought about jumping out and flagging down a

passing car to give us a lift. But they'd all be total

strangers, it was far too dangerous. It was also

obviously dangerous to be sitting in the back of a

car parked at a precarious angle halfway up a hill

heaving with traffic.

'They

will

come back,' I said firmly, trying to

make myself believe it as well as Chris. I made my

voice sound worldly wise and reassuring. 'They just

need a few minutes to calm down.'

I was wondrously right. As I spoke I saw Biddy

tottering back up the hill – and Harry appeared on

the horizon too, strolling down towards us with his

hands in his pockets. They both got back into the

car as casually as if they'd just nipped out to spend

a penny in the public toilets.

Biddy started up the car and we went up and

over the hill, off to Brighton. Biddy and Harry

barely spoke for the rest of the journey.

We had chicken and bread sauce for our lunch

in a café near the beach, and then Chris and I were

allowed to go off together. Biddy and Harry both

gave us money. We scrunched up and down the

pebbly beach, walked to the end of the pier and

back, went all round the ornate pavilion, and

treated ourselves to Mars bars and Spangles, two

Wall's vanilla ice creams, and two portions of chips

with salt and vinegar.

Heaven help us if Biddy and Harry had had

another big row on the journey back. We'd have

both been violently sick.

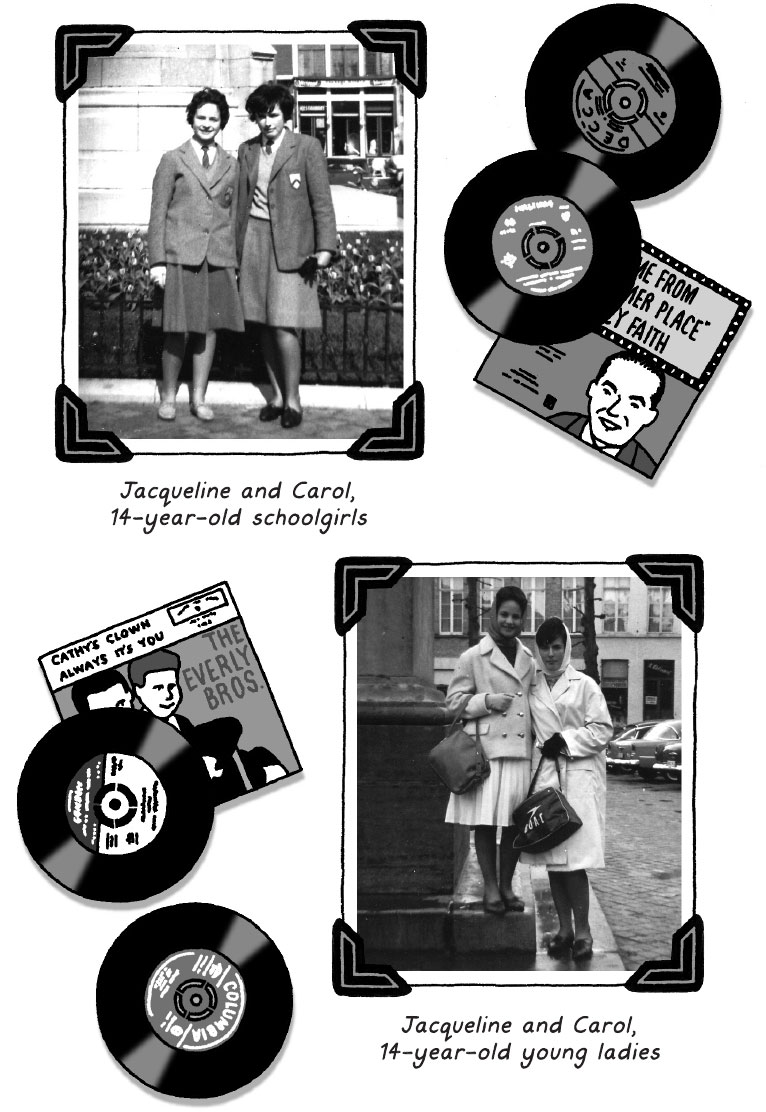

Carol

Girls' friendships are often complex. Chris was

my best friend – but Carol was too. She lived

in Kingston so we went home from school together,

and we spent a lot of time in the holidays with each

other. Both our mothers worked full-time so Carol

and I spent day after day together.

I can't clearly remember going to Carol's house.

I hardly knew her family. I met her mother but I

can't remember her father. Carol had an older

sister, Margaret, but she wasn't chatty and cosy

like Jan, Chris's sister. I don't think she ever even

spoke to me. Margaret looked years older than her

age. She wore lots of make-up and high stiletto

heels and had many boyfriends.

Carol seemed to be heading that way too. She

was a dark, curvy girl with very white skin and

full lips. By the time we were fourteen she could

easily pass for seventeen or eighteen. She

effortlessly managed all those teenage female

things that I found a bit of a struggle: she plucked

her eyebrows into an ironic arch, she shaved her

legs smooth, she styled her hair and tied a silk

scarf round it just like a film star. She was as

expert as her sister with make-up, outlining her

eyes and exaggerating her mouth into a moody

coral pout.

Carol could be moody, full stop. I went round

with her for several years but I never felt entirely

at ease with her. We'd share all sorts of secrets but

I always felt she was privately laughing at me,

thinking me too earnest, too intense, and much

too childish. Carol had two other friends, Linda

and Margaret, sophisticated girls who flicked

through the beauty pages of women's magazines

in the lunch hour and yawned languidly because

they'd been out late the night before with their

boyfriends. I'd sit with the three of them each

lunch time and feel utterly out of things. I'd risk

a comment every now and then and catch Carol

raising her immaculate eyebrows at Linda

and Margaret.

She never openly criticized me, but sometimes

it was the things she

didn't

say that hurt the most.

I remember one time in the holidays I'd been

maddened by my wispy hair straggling out of its

annual perm. I'd taken myself off to a hairdresser's

and asked for it to be cut really short. A few avant-garde

girls were sporting urchin cuts that year and

I thought they looked beautiful.

The trouble was,

I

wasn't beautiful. I was

appalled when I saw my terrible new haircut. It

cruelly emphasized my glasses and my sticky-out

ears. I went home and howled.

I was meeting Carol that afternoon. I felt so

awful walking up to her and seeing her expression.

I badly wanted her to say, 'Oh, Jacky, I love your

new haircut, it really suits you.' We'd both know

she was lying but it would be so comforting all

the same.

Carol didn't say a word about my hair – but

every now and then I caught her staring at me and

shaking her head pityingly.

However, we did sometimes have great fun

together. We both loved to go shopping, though

neither of us had much pocket money. Kingston

has always been a good town for shopping, though

in 1960 Bentalls was just a big department store,

not a vast shopping centre. We wandered round the

make-up and clothes but we never actually bought

anything there.

We had two favourite haunts, Woolworths and

Maxwells. When I was fourteen, Woolworths was

considered cool, a place where teenagers hung out.

There was no New Look or Claire's Accessories

or Paperchase or Primark or TopShop. I spent my

pocket money in Woolworths. I walked straight

past the toy counter now (though when Carol

wasn't watching I glanced back wistfully at the

little pink penny dolls) but I circled the stationery

counter for hours.

It was there that I bought the red and blue

sixpenny exercise books, or big fat shilling books

if I was really serious about a story idea. I was

forever buying pens too – red biro, blue biro, black

biro, occasionally green – that was as varied as it

got. There were no rollerballs, no gel pens, no felt

tips. There were fountain pens but they didn't have

cartridges then, so you needed a bottle of royal-blue

Quink, and I always ended up with ink all

over my fingers. I used to think that if I could only

find the perfect notebook, the most stylish pen, my

words would flow magically.

There's a little childish bit of me that still

thinks that. I've got more ambitious in my taste.

I thumb through beautiful Italian marbled

notebooks now, trying to choose between subtle

swirling blues and purples, pretty pale pinks and

blues, bold scarlet with crimson leather spines and

corners, wondering which is the luckiest, the one

that will help me write a truly special story. I've

bought a handful of expensive fountain pens, but

I

still

end up with ink all over me so I generally

stick to black miniballs.

I liked Woolworths jewellery too, big green or

red or blue glass rings, 'emeralds' and 'rubies' and

'sapphires', for sixpence, and I loved the Indian

glass bangles, treating myself to three at a time:

pink and purple and blue. Biddy said it was

common wearing so much jewellery at once. We'd

both have been astonished to see me now, huge

silver rings on every finger and bangles up to

my elbows!

Monday 4 January

Met Carol in Kingston this morning. (We are still

on holiday, go back to school next Wed. worst luck.)

I bought a new pen from good old Woolworths, a

pair of red mules, and some tomatoes for my lunch.

Woolworths sold old-lady slippers, cosy tartan

with pompoms on the top, but of course I didn't

want a pair of these. They were definitely grandma

territory, and much as I loved Ga, I didn't want to

look like her. No, these were special Chinese scarlet

satin embroidered mules, incredibly exotic for

those days. I was particularly keen on anything

Chinese since reading a highly unsuitable adult

book called

The World of Suzie Wong

by Richard

Mason. Biddy might fuss excessively about the way

I looked but she didn't always manage to monitor

my reading matter.

Suzie Wong was a Chinese prostitute living in a

house of ill repute in Hong Kong. I thought her

incredibly glamorous. I didn't necessarily want to

copy her career choice, but I wished I

looked

like

Suzie Wong: long straight glossy hair, and wearing

a silk embroidered cheongsam split to the thighs.

Both were way beyond my reach, but I

could

sport Chinese slippers from Woolworths. Well, I

couldn't

wear them actually. They were flat mules

and I had the greatest difficulty keeping them on

my feet. I walked straight-legged, toes clenched,

but could only manage a couple of steps before

walking straight out of them. I didn't care. I could

simply sit with my legs stuck out and

admire

them.

We never went shopping in Kingston without

going into Maxwells. It sold records. There

weren't any HMV shops selling CDs in those days,

let alone songs to buy on iTunes. Singles came

on little '45' records in paper sleeves. They were

actually doubles rather than singles, because each

record had an A side (the potential chart topper),

and then you flipped it over to the B side. You

listened to the top twenty records in the hit

parade on your little portable radio – only I didn't

have one till I was fifteen, and I couldn't tune

our big old-fashioned Home Service wireless to

trendy Radio Luxembourg. I simply had to go to

Maxwells with Carol and listen there. You told

the spotty guy behind the desk that you wanted

to listen to several records – Carol would reel

off three or four likely titles – and then he

would give them to you to take into the special

listening booth.

We'd squash in together and then, when we

started playing the records, we'd bob up and down

in an approximation of dancing and click our

fingers in time to the music. We considered

ourselves very hip.

Sometimes there were other girls in the next

listening booth. Sometimes there were boys, and

then we'd bob and click a little more and toss our

heads about. Sometimes there were older men,

often comic stereotype leery old men in dirty

raincoats. They'd peer through the window at us,

their breath blurring the glass. We'd raise our

eyebrows and turn our backs, not too worried

because we were together.

We rarely

bought

a record. We played them

several times and then slipped them back into their

sleeves and returned them to the spotty boy.

'Sorry, we can't quite make up our minds,'

we'd chorus, and saunter out.

Up until January 1960 I didn't even have a

record player so it would have been a pointless

purchase anyway. We had my grandparents'

gramophone, one of those old-fashioned wind-up

machines with a horn, but it wouldn't play modern

45 records. We had a pile of fragile 78s, that

shattered if you dropped them, and I had my

childhood Mandy Miller records, 'The Teddy Bears'

Picnic', 'Doing the Lambeth Walk', and some Victor

Silvester dance music. They weren't really worth

the effort of strenuous handle-winding. But on 9

January everything changed.

I did the shopping with Dad and you'll never

guess what we bought! A RECORD PLAYER! It

had previously been £28 but had been marked

down to £16. It is an automatic kind and plays

beautifully. We bought 'Travelling Light' by Cliff

Richard and Dad chose a Mantovani long player.

It sounds very square but actually it is quite good

with some nice tunes like 'Tammy', 'Que Sera

Sera', 'Around the World in 80 Days'. I've been

playing them, and all our old 78 records, all

the afternoon.

I know, I know – Cliff Richard! But this wasn't the

elderly Christian Cliff, this was when he was young

and wild, with sideburns and tousled hair, wearing

white teddy-boy jackets and tight black drainpipe

trousers, very much an English Elvis, though he was

never really as raunchy as Presley. I remember Celia,

a lovely gentle girl in my class who was very into pop

music. Her mother was too, surprisingly.

'My mum says she'd like to put Cliff to bed and

tuck him up tight and give him a goodnight kiss –

and she'd like to put Elvis to bed and get in beside

him!' said Celia, chuckling.

Celia knew the words to every single pop

song and would sometimes obligingly write them

out for me in her beautiful neat handwriting.

I would solemnly learn every single

bam-a-wham-bam

and

doobie-doobie-do

and also try hard

to copy Celia's stylish script. There are passages

in my diary where I'm trying out different

styles, and it's clear when I'm doing my best to

copy Celia.

I saved up my pocket money to buy another

record the very next week: Michael Holliday's

'Starry Eyed'. It was currently Carol's favourite

song and so we could do a duet together, though

neither of us could sing to save our lives.

I didn't buy another record until March, when

I decided on the theme tune from

A Summer Place,

a very sugary recording, all swirly violins, but I

declared it 'lovely'. I had no musical taste

whatsoever at fourteen. I'm astonished to see I next

bought a Max Bygraves record, 'Fings Ain't Wot

They Used t'Be'. I can hardly bear to write those

words on the page!

By August I was staying up late on Saturday

nights listening to David Jacobs's

Pick of the Pops

,

and hearing 'Tell Laura I Love Her' by Ricky

Valance for the first time. I

adored

'Tell Laura'.

It was like a modern ballad poem, a tragic

sentimental song about a boy called Tommy trying

to win a stockcar race in order to buy his girl a

diamond ring. Each verse had a chorus of '

Tell

Laura I love her

' – and of course Tommy's dying

words from his wrecked car were '

Tell Laura I love

her

'. I didn't take the song

seriously

but loved

singing it over and over again in a lugubrious voice

until Biddy screamed at me to stop that stupid

row

now

.

Thank goodness my taste developed a little over

the next year – in the summer of 1961 I discovered

traditional jazz. I fell in love with all the members

of the Temperance Seven, a stylish crowd of ex-art

students who dressed in Edwardian costume.

'Whispering' Paul McDowell sang through a horn

to make an authentic tinny sound. It was the sort

of music my grandparents must once have played

on their wind-up gramophone, but it seemed mint-new

and marvellous to me: 'I bought Pasadena, it's

an absolutely fab record and I've now played it at

least 50 times.'

I went to see the Temperance Seven at Surbiton

Assembly Rooms, and when I was sixteen I used

to go up to London to various jazz cafés in Soho

with a boyfriend. That was way in the future

though. I might manage to just about

pass

for

sixteen when I wanted to get into an A film at the

cinema – but I certainly didn't act it.