Nabokov in America (32 page)

Read Nabokov in America Online

Authors: Robert Roper

He had sent White something else instead, a story about Pnin, a Russian-born professor, which

was

suitable. Writing that and writing the installments of

Speak, Memory

had been “brief sunny escapes” from the other book, the one that had tortured him. Nabokov both wanted and did not want to show White

Lolita

. He was obliged to, under their contract, and he hoped that she would declare it a work of genius despite its treatment of depravity, of such incomparable merit that all worries about public revulsion or possible prosecution could be forgotten. White was not charmed, however, by the unsigned manuscript that

Véra hand-carried

27

to New York a few months later, at the end of ’53. The

New Yorker

’s head editor, William Shawn, was not to be shown it by any means, Véra insisted to White—Shawn was

more shockable

28

than she was.

The writing of a classic novel thus passed, was accomplished, marked by a few comments to an editor (“heartbreaking,” “enormous”) and by

a hint or two

to friend Wilson

29

(“quite soon I may show you a monster”). White had no doubt heard this sort of thing before: writers often think their latest work their greatest. He continued dictating that fall, recording only

on the sixth

30

of December that he was truly finished. “The theme and situation are decidedly

sensuous,” he told Wilson, but “its art is pure and its fun riotous.” It was his “best thing in English.” One of the first editors to see the manuscript warned him, however, that “we would all go to jail if the thing were published. I feel rather depressed about this fiasco

31

.”

The publication of

Lolita

, like its composition, was long and

tormenting

32

. At times it seemed unlikely to be accomplished. Nabokov acted

as his own agent

33

, as Wilson had taught him to. Viking rejected it first, an editor warning that publication under a pseudonym, Nabokov’s initial plan for the book, would invite prosecution, reluctance to affix an author’s real name suggesting awareness of pornographic content. Simon & Schuster rejected it next, editor Wallace Brockway blaming the decision on prudish colleagues. In October ’54, J. (James) Laughlin, bold avant-gardist not afraid to challenge obscenity statutes, said no for New Directions. Farrar, Straus & Young declined out of fear of a court battle they could not win. Jason Epstein, of Doubleday, had been tipped to the book by Wilson, who was given a manuscript in late ’54; like Pascal Covici, the Viking editor, and like Brockway, and like Roger Straus of Farrar, Straus,

Epstein esteemed

34

Nabokov’s writing but was unable to persuade his colleagues to publish the new book, and in a memo he expressed some literary reservations but also a feeling that

Lolita

was somehow and not in a trivial way, brilliant.

Laughlin and Covici thought it might have

a better chance

35

overseas. Nabokov therefore sent it to Doussia Ergaz, his agent in Paris, and started looking around for an American agent to do what he had been unable to—he was

willing to part

36

with 25 percent of earnings, he told Brockway.

This complicated process, which did lead eventually to a foreign first publisher (Olympia Press) and finally to an American one (Putnam’s), seems in retrospect fated to have worked out. The book was sexual but demure: free of forbidden words. It was highly readable. It appeared at a good moment, when the enforcers of public morality were coming to seem completely absurd. Joyce’s

Ulysses

, widely acknowledged as an iconic work, possibly the greatest of the century, had been under attack by moral guardians since before it was even a book. (A first excerpt, published in 1918,

brought convictions

37

for obscenity for the two editors

of the

Little Review

.) A long line of other works, condemned, confiscated, and burned, including Lawrence’s

Women in Love

,

The Well of Loneliness

, by Radclyffe Hall,

Tropic of Cancer

,

Tropic of Capricorn

,

Naked Lunch

, Ginsberg’s “Howl,” Dreiser’s

An American Tragedy

, Erskine Caldwell’s

God’s Little Acre

, Lillian Smith’s

Strange Fruit

, and

Memoirs of Hecate County

, had pre-dug Nabokov’s

rose garden

38

. Just in the years between his book’s first rejections (’54) and its acceptance by an American house (’58), the censorship effort in America went from weak to moribund, and by ’59

Lady Chatterley’s Lover

, the most suppressed novel of the century, had appeared in

paperback from Grove

39

Press, and in ’61

Tropic of Cancer

also appeared, also from Grove.

It was fated to work out for other reasons, too. Though Nabokov told Katharine White that

Lolita

was “a great and coily thing” without precedent, it was not a formal breakthrough on the order of

Ulysses

or

The Sound and the Fury

, or

As I Lay Dying

(or

Moby-Dick

, for that matter). It did not present difficulties for readers like those to be found in Djuna Barnes’s

Nightwood

or Andrei Bely’s

Petersburg

or, to name works only of

Lolita

’s own decade, Beckett’s

Molloy, The Voyeur

, by Robbe-Grillet,

The Recognitions

, by William Gaddis, or Michel Butor’s

Second Thoughts

. Within Nabokov’s own canon it was easier to enter than

The Gift

or

Bend Sinister

. If by “without precedent” he had meant the

theme of sex with children

40

treated openly, on that score he would have been exaggerating his book’s originality; disturbing accounts had appeared before, in works by the Marquis de Sade (

The 120 Days of Sodom

,

Incest

) and others. Nabokov meant something else by “without precedent.” Probably he meant the coily, intricate skein of correspondences half-buried in the text, hints whereby Humbert becomes aware of Quilty, whose string pulling mirrors his own but on a level suggestive of devilish intriguing, of a universe of mocking gods, with a Master Pratfall Designer up there somewhere, ensnaring everyone in a stupendous gag.

Whatever he meant, he had written

a novel for readers

41

: ordinary readers. It was decked with gaudy allures, wickedly funny, sure to offend, but with its doors wide open. Altagracia de Jannelli would have approved. She had wanted him to write something right over the American plate. In all his magpie gleaning of period objects and attitudes he had managed not to overlook simplicity and emotion as American preferences. The book sold well for Olympia, despite legal challenges in Britain and France, and for Putnam’s and later American publishers it

sold extremely well

42

—phenomenally well, in the hundreds

of thousands in just its first year, and in ensuing decades in the many, many millions.

Some of Nabokov’s struggle as he wrote came from fear that his new book would be stillborn—would be suppressed, kept from all those readers. Writers are a varied bunch, some concerned about readership, some indifferent, but even the indifferent ones write with at least one reader in mind, working to entice and seduce and impress themselves. To give up five years of professional prime and his

best work

43

in English, as he decreed

Lolita

to be—to carry the child full-term, knowing that it might already be dead—that was indeed anguishing.

His superciliousness, his scorn for all that was popular and midmarket, was an authentic attitude with him but also a deception. His novel

Pnin

was valuable and justified as a work of art because “what I am offering you,” he told one publisher who became interested in it, “is a

character entirely new

44

to literature … and new characters in literature are not born every day.” Novelty was what justified

Lolita

, too, he felt—being without “precedent in literature.” Luckily, to have the sense of originality he needed in order to write did not require an

As I Lay Dying

type text, structurally strange and forbidding to mainstream readers. He had written such books, plentifully forbidding ones—

Bend Sinister

was his modernist American swan song, unfriendly to many reader expectations, and some of his Russian novels, such as

Invitation to a Beheading

, rejoice in narrative discontinuities and redressings of reality.

Reality, identified by Nabokov as “

one of the few words

45

which mean nothing” without quote marks around them, signified something new in the New World. Reality was vital and vulgar here. It provided Nabokov with “

exhilarating

46

” opportunities for burlesque, for extended high-flying parodies, and the books of his American prime are excited even when dark. Readers puzzled or disgusted by the

high spirits

47

of

Lolita

, which he himself deemed a tragedy, were not misperceiving it; the energy of discovery—the pleasure in claiming new writerly territory—skews the representation. But that reality is also fairly stable. In

Pnin

the quote marks around it have been all but erased, and a reader of

Lolita

, especially of the road-trip parts, might almost have used it as a Baedeker. In

Ada

, written after his self-exile to Switzerland, the reality of countries and continents is an idea again under interrogation. Use

Ada

as Baedeker at your peril.

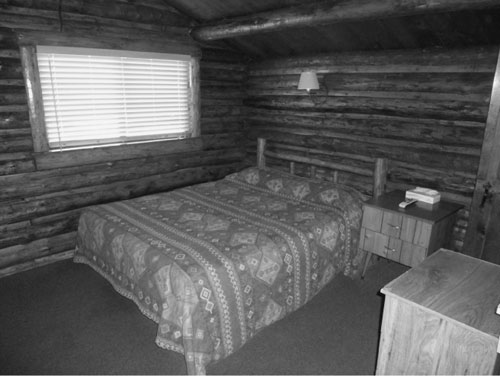

Summer

of ’54, the Nabokovs had a rare bad western trip: a cabin they rented turned out to be a mess—it was ten miles north of Taos, New Mexico, “an ugly and dreary town,” Nabokov wrote White, with “

Indian paupers

48

placed at strategic points by the Chamber of Commerce to lure tourists from Oklahoma and Texas.” Then Véra found a lump in her breast. A local doctor said it was cancerous, and she rushed east by train, to a doctor in New York who removed the lump and found it to be benign. Before this, which put an end to the New Mexico trip, Vladimir had asked a local man to introduce him to Frieda Lawrence, D. H. Lawrence’s

notorious widow

49

, who lived on a ranch nearby. Véra refused to go with him; she had no interest in meeting such a woman, and she discouraged him from going

on his own

50

. The Lawrence ranch, where the writer’s ashes had been brought after his death in southern France, had been given to Frieda by the arts patron Mabel Dodge Luhan, and it had become a place of pilgrimage for devotees, who ventured to it as to a shrine. Nabokov’s attentions to graves and writers’ widows are little known—in America, this appears to have been his only attempt to pay such respects.

He worked hard the year

Lolita

was being rejected. Among his projects was a translation into Russian of

Speak, Memory

, a “most harrowing” task, he informed White. “I think I have told you more than once

what agony it was

51

… to switch from Russian to English… . I swore I would never go back, but there I was, after fifteen years … wallowing in the bitter luxury of my Russian.” He continued working on

Eugene Onegin

, translating the other direction. He wrote a second chapter of

Pnin

, deemed “unpleasant” by the

New Yorker

and rejected; Viking had acquired book rights, but his editor there felt unsure after reading the early chapters and disagreed with Nabokov’s overall plan, which ended in death for “

poor Pnin

52

… with everything unsettled and uncompleted, including the book Pnin had been writing all his life.” Speaking Jannellian

market wisdom

53

, the editor, Pascal Covici, urged an outcome a little less hopeless, and Nabokov took this advice: he changed his plan.

Pnin

shows him performing as an alert professional, writing about a Russian in America after the death of Stalin and during Joseph McCarthy’s hunt for Soviet moles—a time of

unusual focus on things Russian

54

. The book is of the early fifties as

Lolita

is of the late forties and a bit later. Michael Maar, a German scholar, notes that “the mushroom cloud over Hiroshima” makes its way into the text, Professor Pnin reminded of it when he sees a

thought bubble

55

in a cartoon, and in general, “

no other work

56

by Nabokov lets so much contemporary history

pass through its membranes.” The writing is social comedy of an exalted sort. Mary McCarthy had published

The Groves of Academe

in ’52, and Nabokov read it and pronounced it “

very amusing and quite brilliant

57

in parts.”

Pnin

is, like hers, a

campus novel

58

, but Nabokov, although he holds some characters up to ridicule, and though he takes aim at a discrete social world, writes a few degrees off true north of social satire, not much concerned to shape a thoroughgoing critique of anything. Pnin is a good soul and an honorable man. He patronizes a local restaurant, the Egg and We, out of “

sheer sympathy

59

with failure,” and his byword is kindness. He has been through the century’s wringer. Now he finds himself in a land of excellent washing machines: