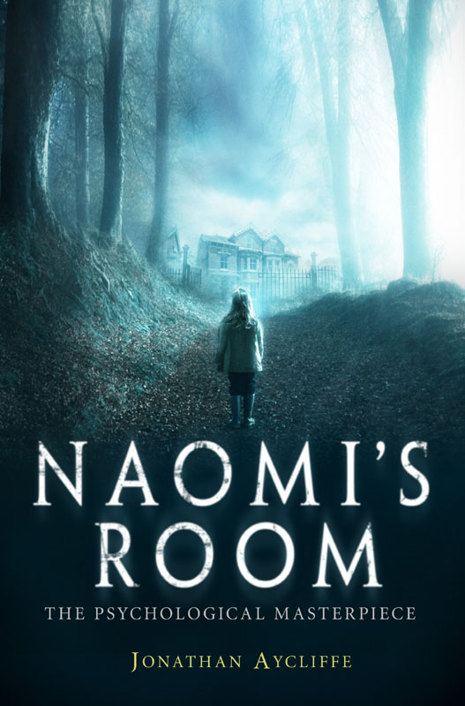

Naomi's Room

Authors: Jonathan Aycliffe

Jonathan Aycliffe

was born in Belfast in 1949. He studied English, Persian, Arabic and Islamic studies at the universities of Dublin, Edinburgh and Cambridge, and lectured at the universities of Fez in Morocco and Newcastle upon Tyne. The author of several ghost stories, he lives in the north of England with his wife. He also writes as Daniel Easterman, under which name he has penned several bestselling thrillers.

By the same author (writing as Daniel Easterman)

The Seventh Sanctuary

The Ninth Buddha

Brotherhood of the Tomb

Night of the Seventh Darkness

The Last Assassin

Jonathan Aycliffe

Constable & Robinson Ltd.

55–56 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published by HarperCollins, 1991

This edition published in the UK by Robinson,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd., 2012

Copyright © Denis MacEoin, 1991

The right of Denis MacEoin to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or to actual events or locales is entirely coincidental.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in

Publication Data is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-47210-509-7 (ebook)

For Beth,

a spine-warmer if ever I met one

Many thanks to everyone involved in this venture into the supernatural: my sceptical but always delightful editor Patricia Parkin; my wife Beth, whose own fascination with ghost stories encouraged me to attempt the genre; Alan Jessop Sr, who proved a most amiable and knowledgeable guide to Spitalfields; the resourceful Chris Jakes of the Local Studies department of the Cambridge Public Library, who steered me through maps and guides with great clarity; and Roderick Richards of Tracking Line, who sorted out my Metropolitan from my City police.

Naomi’s prayer on pages 22–3 is taken from a genuine case history cited by Harris Coulter in his fascinating study

Vaccination, Social Violence and Criminality: the Medical Assault on the American Brain

(pp. 74–5).

I found them yesterday, quite by chance. The photographs. The ones we took at Christmas all those years ago. And the later ones, the photographs we took in Egypt. Memories of an entire winter. I had thought them lost or destroyed. Perhaps I had wanted it that way.

They were in a box in the loft, a tin box that had once held a cake from Betty’s Teashop in Harrogate. A ginger and walnut cake, the sort you have with a slice of Wensleydale and a cup of China tea. I don’t know how the photographs came to be inside: I am sure I did not put them there. And I know that Laura could not have done so.

In any case, I shall make quite sure this time, I shall burn them. I have a little bottle of kerosene, quite enough for my purpose. I shall take them out to the garden this evening and light a small fire near the ash tree and consign them to the flames. The past is long ago consumed. It will not matter. Perhaps the act of burning will give me a little peace. How sweet that would be. A little peace. Outside, the sun is the colour of yellow marble. There is frost on the wall.

Was it quite by accident that I found them? Or was I led there by a reactivation of memory, a guiding instinct that had lain dormant year after year until now, in the cold days of my life, something wakened it? It is precisely twenty years since those events, the events the photographs in part record. It all started and ended here in Cambridge, in this house, in these rooms. The walls remember just as well as I. Why should those happenings not find their echoes here?

I dreamed my dream last night again. It has not visited me in many years. Is she here again? Will she be here with me tonight? I shall go to church today, I shall light bright candles against the possibility.

That ash tree in the back garden was much smaller then. I was thirty, Laura twenty-six. We had been married five years. And Naomi, Naomi was four. The college favourite, the Dean’s pet. I had just been awarded my fellowship, and we had moved from the college flat off Huntingdon Road to this house in Newtown. Your life seems so directed when you are thirty, the years are taken care of, there is a patina on things, there are fewer edges from which to slip. The house was to be our home for as long as we could imagine, until my professorship at least. There would be a second, perhaps a third child. There would be a Christmas tree in winter, tea in the afternoons, toast by an open fire, the sound of a piano in the late evening, notes like snowflakes falling through the still evening air. Your life seems so directed when you are thirty.

I had written my thesis on the meaning of Christmas in

Gawain and the Green Knight

. The University Press had offered to publish it once I’d knocked it into shape. I made love to Laura almost every night, there was a fire inside me. And Naomi used to play on the landing outside my study, laying her plastic dolls with a child’s care beside my door, singing to them in an unsteady voice:

Oranges and Lemons

Say the bells of St Clement’s.

I heard her sing it again last night, in my dream.

The winter of 1970 was cold in Cambridge. Throughout November there was heavy rain. Gales blew. The fields were soaked and flooded. The beginning of December was dry, its second half cold with showers of snow. Frost dripped from bent trees, mist curtained the Backs most days, snow lay in driven patches on the roofs of the colleges. The walls of my study were warm with the red and green and brown spines of books. Old leather, the gleam of gold letters. I spent a lot of time indoors, reworking my thesis, preparing lectures, playing with Naomi.

Most days, she and I would walk down Trumpington Street together as far as Pembroke, where I picked up any mail that had been sent there for me. Afterwards, it was a walk of only a few yards to Fitzbillies for cakes. She loved their Chelsea buns, great sticky buns that she would hold in a tiny fist with a curious dexterity. Then we would set off home, hand in hand, along half-empty streets, Naomi swinging a paper bag gaily by her side. It grew dark early. We passed lights behind mullioned windows, fires in grates, the sorcery of the cold season. I remember her best by lamplight, my daughter, in a yellow coat and a red muffler.

One day, the Christmas lights went on in Sidney Street. This was to be Naomi’s first proper Christmas. Her excitement was infectious. Laura and I went out to Deers, the nursery on the corner of Huntingdon and Histon Roads, and brought home a tall tree. With Naomi’s help, we covered it with lights and tinsel. A Burne-Jones angel stood at the very top, her russet hair grazing the ceiling, ringed by coloured lights. Naomi would stand for what seemed like hours watching reflections of the room in a large silver ball that turned slowly on the lowest branch. One night she fell asleep at the foot of the tree, a piece of blue ribbon clutched tightly in her hand. On the radio, carols were playing.

I saw three ships come sailing in on Christmas Day, on Christmas Day

. . .

On Advent Sunday, we went to the Wren chapel in college for the carol service. Naomi walked between us, solemn-faced like a Victorian child, tiny hands in a huge fur muff. The voices of the choir had a strange quality that year. I have never heard them sing like that since. It was as though they themselves were not singing, but through them generations of choristers had access once again to song. In the intervals, the congregation would burst into fits of stifled coughing. But in those moments of singing no one moved. All about us, stained glass melted in the light of perfect candles.

We were not particularly religious. Both Laura and I had been brought up as Anglicans, but our faith was a sporadic thing, a celebration of Christmases and Easters, weddings and burials. But in those moments of Advent, in the high chapel, wrapped by exquisite song, we almost believed. I believe now, but for different reasons. It is not the beauty of glass or the light of the world that have brought me to faith. It is fear. Simple, complete, and perfect fear.

Naomi could hardly be put to bed that night. She wanted me to sing to her, to teach her carols for the child Jesus. She was one of those children who can be taken to concerts and religious services without cause for embarrassment. Her manner was serious, even solemn at times. And beneath that, a laugh so light it seemed without substance. Even at play she would be solemn, then the laugh would break through, transforming her face. I loved her so much. More than I loved Laura, I think. Perhaps fathers always love daughters in that way.

There are so many photographs, more than I had remembered. I have laid them on the kitchen table in long rows, like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. I am in very few of them, I was usually the photographer. Here is one of Laura in front of King’s College, smiling like a tourist. Behind her I can make out a fine sprinkling of snow on the Parade and on the short strip of grass in front of the college wall. You can just make out the east window of the chapel in the background.

Here is Naomi standing by that Christmas tree, a jumble of unopened presents by her feet, the blue ribbon in her hand. That was taken by someone else, I can’t remember who, Galen perhaps, or Philip. It shows all three of us, Laura, Naomi, myself, at a Christmas tea in the senior common room. That must have been about a week before term ended. I seem to remember a conversation about metaphor. That would have been Randolph.

I was lecturing on

Beowulf

that term, to a second-year group. On Tuesdays and Thursdays I held tutorials in my room at college, a fine old room overlooking the college garden. Pembroke is a college mercifully off the tourist trail, it has none of the architectural grandeur of King’s or Trinity or John’s. Americans and Japanese avoid it. But there are some visitors who come for the chapel, Wren’s first commission, and a very few who seek a sort of peace there, as though they had come to a cloister in a moment of need.

I still have that room, I still see tutees in it, at moments I still rise from my chair and look through my window on to one of the world’s quiet places, but I have no peace. I am uncloistered. My moment of need has been and gone.

Laura spent the days with Naomi. She had given up her job at the Fitzwilliam Museum shortly before our daughter was born. It hadn’t been much of a job, mainly cataloguing and fetching papers for readers. She had a first-class degree in Art History, had been offered a place to carry out postgraduate work at Newnham, but had opted instead for marriage and motherhood. The plan was that she would reapply and start work on her PhD as soon as Naomi started school. She had her subject already: sexuality in the paintings of Balthus. We made so many plans, we were architects of our own lives.

This is a photograph of myself, one of the only ones from that period. I’ll burn it along with the rest. In for a penny . . . I hardly recognize myself: long black hair to the shoulders, a weak beard, a slightly arrogant expression, the smugness of a young don who knows he cannot put a foot wrong. I led a charmed life: a beautiful wife, a perfect daughter, a tenured post in one of the great universities. A photograph taken of me today would show none of those things. I no longer have such presumptions on life, my expectations are quite different. But I haven’t let anyone take my photograph in years.