Neil Armstrong: A Life of Flight (39 page)

Read Neil Armstrong: A Life of Flight Online

Authors: Jay Barbree

Tags: #Science, #Astronomy, #Biography & Autobiography, #Science & Technology

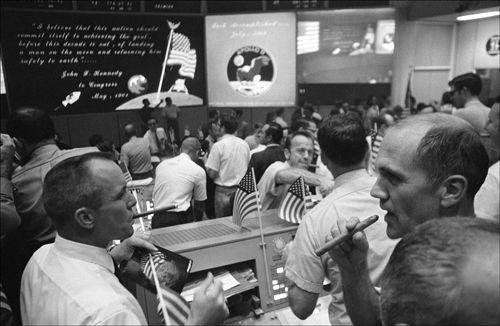

CapCom Charlie Duke, who would later walk and drive a lunar buggy on the moon, was on pins and needles during the landing. Backing up Charlie sitting on his left was famed

Apollo 13

commander Jim Lovell and lunar module pilot Fred Haise. (NASA)

A momentary smile crossed his face. Now let us see if those 61 LLTV training flights were worth it, the training he needed to land on the moon. Neil was betting they were. He was hopeful they had given him the skills to get the job done.

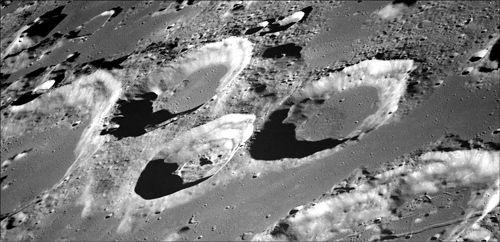

He looked through his triangular window and studied the desolate, crater-pocked surface before him. He had made many simulated runs, pored over dozens of photographs taken by

Apollo 10

marking the way, landmark by landmark, down to the Sea of Tranquility. He knew their intended landing site as well as he did familiar airfields back home, and he immediately noticed they weren’t where they were supposed to be. Damn!

Eagle had overshot by four miles. A slight navigational error and a faster-than-intended descent speed accounted for their lunar module missing its planned touchdown spot. Neil studied the rugged surface rising toward him and Buzz noted a yawning crater wider than a football field. Eagle was running out of fuel and headed straight for the gaping lunar pit filled with boulders larger than a Purdue jitney.

Neil studied the rugged surface rising toward them. He had made so many simulated runs that he suddenly realized they had overshot their landing mark by four miles. (NASA)

Scientifically it would be great to land next to and explore a crater gouged into lunar soil but Neil quickly ascertained the slope around it was too steep. If Eagle landed on a tilt they could never launch back into orbit.

With not a second to waste Neil realized he was on his own. This was where experience and training came into play and he looked beyond the crater. Landing Eagle was a matter of piloting skills he’d been honing. Against the wishes of Director of Flight Operations Chris Kraft, he had spent more time in the Bedstead, the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle, than any astronaut and now it was paying off. He needed to bring Eagle in to a smooth surface not by hovering and dropping, but by flying, by scooting across the lunar landscape as he had trained in the LLTV. There was only this one chance.

He gripped Eagle’s maneuvering handle and translator in his gloved fists with a touch honed by years of flying the smallest and the largest, the slowest and the fastest—Neil knew the “thin edge” well, hell he had written it, and he had to fly as he’d never flown before. Knowledge, experience, touch—the skill of flying the

Gemini 8

emergency from orbit, bringing the X-15 rocket plane in from its Pasadena flyover, ejecting from his crippled jet fighter over Korea, and ejecting from the lunar landing trainer itself seconds before crashing—all of it, everything, came to this one moment.

Neil’s fingers alternately tightened and eased on the maneuvering handle and translator as they sailed downward at 20 feet per second. He nudged the power, slowing to nine feet per second.

He attuned his senses to the rocking motions and the skids, sixteen small attitude thruster rockets kept Eagle aligned throughout its descent. A level touchdown was their ticket to safety, survival, and the return home.

Mission Control listened. They were mesmerized. They were in awe of the voices closing in on the lunar surface. Neil flew. Buzz watched the landing radar, called out the numbers that represented split-second judgment and flying skills.

Buzz was no novice. Jet-speed combat in his F-86 with Chinese fighters over the ugly mountains of Korea had brought him to this point. He had no questions about the pilot next to him. He was most aware of how Neil thought things through thoroughly and then did what he thought was right and he usually had arrived at the correct decision. Of all the pilots he had met and flown with, Buzz knew, without question none came close to Neil Armstrong. He was simply the best pilot Buzz had ever seen.

“700 feet, 21 down, 33 degrees,” chanted Buzz.

“600 feet, down at 19.

“540 feet, down at—30.

“At 400 feet, down at 9.”

“Eagle, looking great,” Charlie Duke chimed in from Mission Control. “You’re Go.”

Despite the confidence of the astronauts’ voices, there was still a problem: No place to land. Rocks, more boulders, surface debris strewn everywhere.

Neil fired Eagle’s left bank of maneuvering thrusters. The larger rockets scooted the lunar module across rubble billions of years old. Beyond the eons of lunar debris, a smooth, flat area.

“On one minute, a half down,” Buzz told him.

“70,” Neil answered.

“Watch your shadow out there.

“50, down at two-and-a-half, 19 forward.

“Altitude velocity light.

“Three-and-a-half down, 220 feet, 13 forward.”

“Eleven forward. Coming down nicely,” Buzz told him.

Mission Control was dead silent. What the hell could they tell Neil Armstrong? Had they tried Deke Slayton would have killed them.

“200 feet, four-and-a-half down.

“Five-and-a-half down.

“120 feet.

“100 feet, three-and-a-half down, nine forward, five percent.”

“Okay, 75 feet. There’s looking good,” Buzz told him as he stared at the obvious place Neil had chosen to land.

“60 seconds,” Charlie Duke, told them.

Eagle had 60 seconds of fuel left in its tanks and no one wanted to think about it. If the descent engine gulped its last fuel before Eagle touched down, they would crash, falling to the surface without power.

What those in Mission Control did not know was that Neil wasn’t all that concerned about fuel. He felt that once under 50 feet it didn’t really matter. If the engine did quit, from that height at one-sixth the gravity, they would settle safely to the ground.

Neil calmly aimed for his new landing spot. He kept one thought uppermost in his mind: Fly. Eagle swayed gently from side to side as the thrusters responded.

Far away, in Mission Control, flight controllers were almost frantic with their inability to do anything more to help Neil and Buzz.

Deke Slayton knew they had to leave the landing to the pilots. But the clock was ticking away precious fuel. Charlie Duke looked at Deke and held up both hands, palms out. He didn’t need to voice the question. Gene Kranz did it for him.

“CapCom, you’d better remind Neil there ain’t no damn gas stations on that moon.”

Charlie nodded and keyed his mike. A timer stared at him. “30 seconds.”

“Light’s on,” Buzz told Neil as he watched an amber light blink the low-fuel signal.

Buzz then intoned the numbers like a priest, steady and clear, “30 feet, faint shadow.”

“Forward drift?” Neil asked wanting to be sure he was moving toward known surface.

“Yes.

“Okay.

“Contact light.”

Eagle’s probe had touched lunar soil.

“Okay, engine stop.

“ACA out of Detent.”

“Out of Detent,” Neil confirmed. The engine throttle was out of notch and firmly in idle position.

“We copy you down, Eagle,” Charlie Duke told them, and then waited.

Three seconds for the voices to rush back and forth, Earth to the moon and moon back to Earth.

Neil had to be certain. He studied the lights on the landing panel to be sure of what they’d just accomplished.

Four lights gleamed brightly—four marvelous lights welcoming them to another world where no human had ever been. Four lights banished all doubt. Four round landing pads at the end of the Eagle’s legs rested, level, in lunar dust.

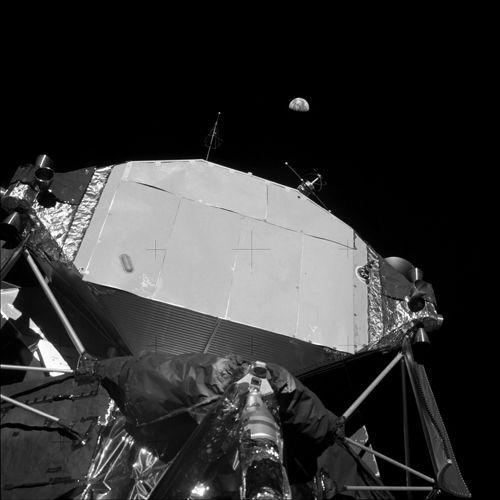

Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin land on the moon. (Composite photograph, NASA)

Neil’s voice was calm, confident, most of all clear, “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

It was 4:17:42

P.M.

EDT, Sunday, July 20th, 1969 (20:17:39 Greenwich Mean Time).

Charlie Duke spoke above the bedlam of cheering and applause in Mission Control.

“Roger, twainquility—Tranquility,” a shaken and happy Charlie Duke answered. “We copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.”

“Thank you.” Neil permitted himself a grin even though he was doing his best to suppress whatever emotions he felt.

Pure, happy bedlam in Mission Control. (NASA)

In their excitement of the moment Eagle’s crew simply shook hands. It was a defining moment in Neil and Buzz’s lives—possibly in the historic significance of what had just happened.

“As the man who jumped off the top of the Empire State Building was heard to say as he passed each floor, ‘So far, so good,’” Neil told Buzz, turning back to their checklists and their chores. They had no way of knowing how long it was going to take them to settle all of Eagle’s fluids and systems, make their moon lander safe for its lunar stay.

To keep from worrying the public, NASA had hoodwinked the media by scheduling a four-hour rest and sleep period for the moon’s sudden population. But the first two people inside a spacecraft on the lunar landscape would not be sleeping. They would be working feverishly to ensure they could stay long enough to take a stroll on the moon, and Neil looked at Buzz, “Okay, let’s get going.”

From 218,000 nautical miles Earth watches over Eagle on the moon. (NASA)

TWENTY

MOONWALK

Neil stared out at the alien world beyond his lunar lander’s window. He was surprised at how quickly the dust, hurled away by the final thrust of Eagle’s descent rocket, had settled back on the surface. Within the single blink of an eye the moon had reclaimed itself as if it had never been disturbed, and Neil studied the desolation surrounding himself and Buzz. No birds. No wind. No clouds. A black sky instead of blue.

They had indeed landed on a dead world. A land that had never known the caress of seas, never felt life stirring in its soil, never felt the smallest leaf drift to its surface. No small creatures to scurry from rock to rock. Not a single blade of green. Not even the slightest whisper of a breeze. They were on a world where a thermonuclear fireball would sound no louder than a falling snowflake.