Neil Armstrong: A Life of Flight (48 page)

Read Neil Armstrong: A Life of Flight Online

Authors: Jay Barbree

Tags: #Science, #Astronomy, #Biography & Autobiography, #Science & Technology

“Sam, this is Jay Barbree.”

“Yeah, Jay, what’s up?”

“What’d you think’s going on with management on the fourth floor?”

“They’re running around, pointing fingers, protecting their asses,” Sam offered.

“Most likely,” I laughed, quickly adding, “Why don’t you go down there and check it out?”

“I could,” he smiled.

“You want a job?”

“Doing what?”

“You could be NBC News’s space analyst for the

Challenger

accident.”

“I could,” he laughed. “It’d keep me outta the pool halls.”

“It would at that,” I agreed.

“Okay, I’ll take a drive down to my old office—see what’s going on.”

“You’re on the payroll, Sam,” I told him, “So keep in touch.”

“I will,” he promised.

* * *

Sam Beddingfield sprung from the same roots my family did in eastern North Carolina. You could trust him with your children. Honesty was a way of life for Sam. He parked himself in the executive offices at NASA headquarters. He listened to everything so far learned. Most of the NASA managers simply thought Sam was still on the job. In the middle of the afternoon, January 30, 1986, two days after

Challenger

disintegrated nine miles above the Atlantic surf, Sam called me.

“I got it.”

“You got what?” I questioned quickly.

“We lost

Challenger

because of a leak in a field-joint,” Sam said flatly.

“An O-ring leak,” I asked?

“That’s it.”

“For sure?”

“For sure.”

“How do they know?”

“They have pictures,” Sam said without hesitation.

“Pictures?”

“Pictures of the leak,” Sam explained. “They show flame blowing out of the sucker like a blowtorch.”

“Where did the pictures come from?”

“From a fixed engineering camera north of the pad.”

“Away from our cameras? Where we couldn’t see?”

“That’s it.”

“What did the leak do, burn into the tank?”

“Not at first,” Sam explained. “It burned through a tank support structure before reaching the tank. Its fuel,” he continued, “fed the flames—hell, they burned everything they touched.”

“And just what caused the leak?”

“My best guess,” Sam explained, “the O-ring was still frozen at launch. The sucker couldn’t do its job.”

“Makes sense,” I agreed before asking again. “We can’t see it on our launch tape?”

“No way.”

“Can you get me those pictures, Sam?”

He laughed. “You trying to get me shot?”

“Not today,” I told Sam, congratulating him again before hanging up and phoning a trusted source at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. She confirmed Sam’s information and with two solid sources we were ready to break the story on Tom Brokaw’s

NBC Nightly News

.

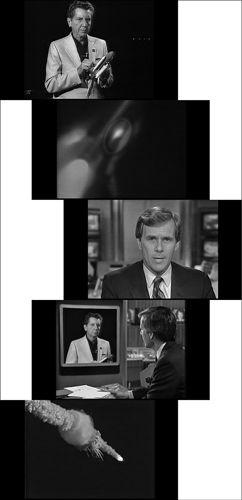

Our producer Danny Noa shoved a small model of the space shuttle in my hands and we opened the show that evening with the story.

Using the model I pointed to the suspected location. I answered Tom’s questions, essentially reporting that the cause of the tragedy was the failure of O-ring seals in the aft field-joint of the right solid rocket motor. The extreme cold had rendered them inflexible. Frozen, the O-rings simply could not do their job.

* * *

No sooner had I left the air than the phone began ringing. Producers Geoff To-field and Danny Noa were fielding most of the questions, but one came in I had to take.

“You looked pretty sharp for a farm boy tonight,” Neil Armstrong said.

“Hey, Neil.” I was grinning all the way through the line. “How’s the milking going?”

“We’re getting a couple of quarts,” he laughed. “What can you tell me you didn’t tell Brokaw?”

“Nothing more, really,” I assured Neil. We talked about what I knew and I promised to keep him up to speed on what I learned. I did, and in less than four months Neil and the Presidential Commission on

Challenger

confirmed my report. In doing so the first man on the moon provided thorough leadership throughout the presidential commission’s investigation, again setting another example to follow.

Tom Brokaw and Jay Barbree breaking what would later be voted the number one story of 1986. (

NBC Nightly News

)

The commission found that the

Challenger

accident was caused by a failure in the O-rings sealing the aft field-joint on the right solid rocket booster. The failure was caused by pressurized hot gases and eventually flame “blowing by” the O-rings. Flame made contact with the adjacent external tank structural support, causing the structure to rupture the tank. The failure of the O-rings was attributed to a design flaw, as their performance could be too easily compromised by such factors as those low temperatures on the day of launch.

The report also determined the contributing causes of the accident were failure of both NASA and its contractor, Morton Thiokol, to respond adequately to the design flaw. The commission offered nine recommendations to improve safety in the space shuttle program.

Neil Armstrong and

Challenger

investigators inspect a space shuttle from beneath. (NASA)

Neil and his fellow commission members summarized their conclusions extremely well in the final report: “The decision to launch the

Challenger

was flawed. Those who made that decision were unaware of the recent history of problems concerning the O-rings and the joint and were unaware of the initial written recommendation of the contractor advising against the launch at temperatures below 53 degrees Fahrenheit and the continuing opposition of the engineers at Thiokol after the management reversed its position. They did not have a clear understanding of Rockwell’s concern that it was not safe to launch because of ice on the pad. If the decision-makers had known all the facts, it is highly unlikely that they would have decided to launch

Challenger

on January 28, 1986.”

The space shuttle’s solid rockets were redesigned as the commission ordered and Neil returned to retired life. “I think our conclusions and findings were right on,” he told me. “It was a very hard-working commission and our answers have never been effectively challenged.… It was a national tragedy,” he continued, “but we learned a great deal from it, and the subsequent shuttle program benefitted. That was ours and spaceflight’s reward.”

* * *

September 29, 1988: Space shuttle

Discovery

sat on its launchpad. Five seasoned astronauts waited: Commander Rick Hauck, pilot Dick Covey, crew members Mike Lounge, Dave Hilmers, and George “Pinky” Nelson. They had been handpicked to return the rebuilt shuttle to flight after seven of their numbers had been lost.

Two hundred and fifty thousand other souls surrounded the spaceport to lend their support. Twenty-four-hundred members of the news media stood at the press site. They were there to report NASA’s comeback from its worst disaster.

At 11:37

A.M.

, eastern time,

Discovery

’s main engines roared. Seconds later the twin solid rockets fired. The assembled thousands crossed fingers and gritted teeth as the two redesigned solid rockets lifted the five astronauts skyward, boosting the space plane and rocket combination straight and true. Two minutes later the huge viewing assemblage broke into wild cheers. The boosters, whose predecessors had been the primary cause of the

Challenger

accident, burned out and peeled harmlessly away from the shuttle and its human cargo. They were the first of 220 of the redesigned solid boosters that would be flown without the slightest problem until they and the space shuttle fleet were retired.

Possibly Neil Armstrong’s greatest legacy following his life of flight as a pilot, engineer, and investigator was the way in which he handled his extraordinary life, which resulted in many of those who would drive aircraft and spacecraft to regard him as one of the best of all times. Neil never thought of himself as special, but everyone else did.

President Ronald Reagan opened an awards ceremony in the White House Rose Garden with the announcement, “America is back in space.”

TWENTY-FOUR

SPACE SHUTTLE AND BEYOND

NASA entered the final decade of the twentieth century fully recovered from its worst spaceflight accident with the agency building on the pioneering work of Neil Armstrong and the astronauts of the space industry’s first three decades. A couple of pretty fair space shuttle drivers Robert “Hoot” Gibson and Charlie Precourt both walked in the shoes of Deke Slayton as chief astronaut. Both played major roles in one of Neil’s oldest dreams—building a permanent space station.

The International Space Station would in some minds be the beginning of an orbiting space city, a gravity-free outpost where Earthlings could multiply, raise families, live longer, and produce the stuff and foods needed for self-sufficiency in space.

But as Gibson, Precourt, and a handful of others knew, the station’s primary job would be to teach humankind how to survive in space. NASA already had a small taste of operating its own space station in 1973 when it used rockets and spacecraft modules leftover from canceled Apollo flights. The agency had launched three separate crews of three astronauts each to spend up to nine months aboard a station named Skylab. The astronauts proved humans could work in space. But soon after the Russians lost the moon race they, too, got serious about space stations. They launched a series of Salyut laboratories, each carrying two or three cosmonaut crews who could stay in space for months.

There was that brief thaw in the Cold War in 1975 when Deke Slayton’s heart was deemed strong enough for space flight. Tom Stafford commanded and Vance Brand rounded out the three-man crew of Apollo-Soyuz. They drove the last Apollo to a rendezvous and docking with the Russians’ Soyuz. Eleven years later, in 1986, Russia sent into orbit what was, to many who made space stuff work, the first real space station. It was called Mir, and cosmonauts stayed aboard their home in the sky for up to a year.

In 1991, as the Cold War ended, Presidents George Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev signed an agreement calling for the first U.S.-Soviet manned space flights since Apollo-Soyuz. It was to include a visit by a U.S. astronaut aboard a Soyuz-TM spacecraft, and a flight by a Russian cosmonaut on a shuttle mission. A major milestone of this agreement occurred on June 29, 1995, when Hoot Gibson and Charlie Precourt docked space shuttle

Atlantis

for the first time with Mir. They exchanged crews and checked out the Earth-orbiting community.

Astronaut Charlie Precourt was one of those directly responsible for helping bring Russia on board as a full member in the U.S.’s plans for building the International Space Station. He reflected on how the first docking with Mir was a beneficiary of the pioneering work of Armstrong and the Apollo astronauts:

Docking the shuttle with the existing Mir station would be our first step in learning to work together to build the International Station. We had done lots of rendezvous missions with the shuttle to retrieve satellites—like when we repaired the Hubble Space Telescope—but we hadn’t yet physically docked with another spacecraft. Mir and Shuttle each weighed over 200,000 pounds and we knew lots could go wrong if we didn’t prepare correctly. Neil’s experience was a critical contributor to our success. We studied the results of the Gemini and the later Apollo dockings and we had procedures for every conceivable combination of thruster issues as well as a number of other potential failure modes. Neil’s first-ever docking of Gemini with the Agena had to be aborted because of a stuck thruster. His quick reaction saved the mission and likely his life. That experience helped every subsequent mission of its kind. Hoot and I, along with our flight engineer Greg Harbaugh, put hundreds of hours into simulations just as Neil did, to test and adjust our plans.

Precourt paused and then continued: “When the day came it went off beautifully. Hoot made contact with Mir at 1.2-inches-per-second in perfect alignment with the Mir docking mechanism. We were within a second of the planned docking time.”