Never Say Genius (24 page)

Authors: Dan Gutman

“It’s just that I’ve visited that museum three or four times already,” Dr. McDonald said, a little whiny. “I’d rather go to someplace I’ve never been.”

Mrs. McDonald shot her husband a look, one of those looks that said he should stop being selfish and think of the children.

Coke was looking over a Washington, D.C., sightseeing map.

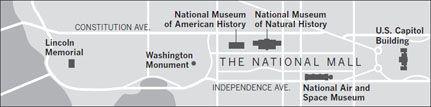

“I have an idea,” he said. “The Museum of Natural History is right next door to the Museum of American History. And Air and Space is right across the National Mall. Pep and I can go to American History while you two go to one of the other museums. That way everybody will be happy.”

“That’s a great idea!” Pep said. “Then we can meet up when we’re done.”

“I don’t know…,” Mrs. McDonald said dubiously.

“Please, Mom…,” Pep begged, making her best puppy dog eyes.

“Are you sure you’ll be okay on your own?”

“Bridge, they’re

thirteen

now,” Dr. McDonald said. “They’re big kids. They can handle themselves in a museum. What could possibly go wrong?”

“Yeah, what could possibly go wrong?” asked Coke, who in the last two weeks had been forced to jump off a cliff, dipped into boiling oil, drowned in ice cream, and gassed in a rest-stop bathroom.

“Well, okay…”

“Yay!”

The family got a late start into Washington because Mrs. McDonald had washed some clothes and needed to wait until they were finished in the dryer before she could leave. Coke used the extra time to load up his backpack with stuff as if he was going on a commando raid. The can of Silly String he’d bought in the Miami County Museum. The duct tape they got in Avon, Ohio. The Frisbee from Bones that said

TGF FLYING HIGH

on it. The little bars of soap that Mya had given them at the motel. Other knickknacks he had picked up at gift shops along the road. You never know what you might need in an emergency.

They got on the Metro and rode it to Gallery Place-Chinatown again. From there, they had to switch to the red line for one stop, and then the blue line for two stops until they reached SMITHSONIAN. That stop empties out right in the middle of the National Mall, a large, grassy rectangle that is surrounded by the Smithsonian museums.

It was a glorious day. The sun was high in the sky, but it wasn’t too hot. The Mall was crowded with people out walking, jogging, riding bikes, and Roller-blading.

Coke pointed out the Capitol building in the distance straight ahead, and the Washington Monument, only a block or so behind them.

The kids knew they didn’t need to be at the museum until two o’clock. That was what the cipher said—July third, two o’clock. Nobody was quite ready to separate just yet. Coke pulled out his Frisbee and threw it to his dad, who threw it to his mom, who threw it to his sister, who threw it back to him. Pep was getting pretty good with a Frisbee, he had to admit. She had finally learned to throw it flat, straight, and true. After a while, they all flopped on the grass and had a little spontaneous picnic, with trail mix and snacks that always seemed to magically appear out of Mrs. McDonald’s purse.

Coke had to remind himself—why were they doing this? He knew somebody or some

thing

was waiting for them inside that museum. He knew it could very well be someone who wanted to kill them. Why walk into a trap?

If he and Pep

didn’t

go, he reasoned, whoever was waiting for them would come and get them. It could be tomorrow, or it could be next week or next month. But there was no avoiding it. And if he was totally honest with himself, he also had an intense curiosity to know who had been sending them all those ciphers, and what they wanted.

Coke checked his cell phone. It was one thirty.

“We should go,” he told Pep.

The Museum of American History is a gigantic, blocky-looking modern building. There was a line of people waiting to get through security at the entrance. Their parents walked the twins to the end of the line and gave them a “family hug.”

“You kids are getting so big, going to museums all by yourselves,” Mrs. McDonald said.

“Be careful in there,” warned their father. “There are pickpockets everywhere, you know.”

“We’ll be fine,” Pep assured them. “Don’t worry about us.”

On the inside, she was thinking that pickpockets were the

least

of her concerns.

Mrs. McDonald pressed a twenty-dollar bill into Pep’s hand and told her to go to the café in the museum if she and Coke got hungry.

“We’ll stay in touch by cell phone and plan to meet up right here when the museums close at five o’clock,” Mrs. McDonald said. “Don’t be late.”

Don’t be late.

The

late

McDonald twins. If something terrible happened, that’s how people would refer to them. Coke shivered and tried to put such thoughts out of his mind.

Pep wondered if she would ever see her parents again. She tried not to cry, taking one last look at her mom and dad as they walked away.

While the twins waited on the security line, Coke played a mental video of the things that had happened to them in the last week. The incident with Archie Clone at the first McDonald’s restaurant. Matching wits with Mrs. Higgins at the Cubs game in Chicago. Visiting Michael Jackson’s boyhood home. Figuring out all the ciphers. Those sadistic bowler dudes. The amusement park in Sandusky, where they’d nearly drowned in ice cream. Sliding down the outside of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Dad going crazy at the Hoover Historical Center when he found out that Hoover was the guy who founded the vacuum cleaner company.

He thought of the miles and miles of highway they had traveled. The strange places they’d visited. Yoyos. Mustard. Duct tape. It had been some trip. They had traveled all the way across the United States now and seen everything from the largest egg in the world to a museum devoted to Pez dispensers. And now they were at the end of the line.

“This is it,” Coke told his sister.

“Let’s go,” Pep replied.

DAY AT THE MUSEUM

T

he twins walked through the metal detector, looking all around for anything suspicious. The security guard peered into Coke’s backpack for a moment, looked at Coke, rolled her eyes, and waved him through. She had seen people try to bring drugs, alcohol, explosives, and even live animals into the museum. Now

this

kid had a can of Silly String, a roll of duct tape, and little bars of soap. Nothing surprised her anymore.

There was no other line, no tickets to be picked up, no admission. The Museum of American History, like all the Smithsonian museums, is free.

Coke and Pep rushed inside. Pep checked the clock on her cell phone. It was 1:46. In fourteen minutes

something

was going to happen. The question was … what?

“I hope Mya and Bones show up,” Coke said.

“They’ll be here,” Pep assured him. “They promised to have our backs.”

“Look!” Coke shouted, pointing straight ahead.

On the opposite side of the museum, nearly filling the wall, was a sculpture made of hundreds of shiny silver panels arranged in the shape of a waving flag. Below it were these words:

The Flag that Inspired the National Anthem

“This way,” Coke said, marching toward it.

The entrance to the Star-Spangled Banner room was below the silver sculpture, on the right. The twins went through the doorway, not knowing what might be around the corner.

When we think of the Star-Spangled Banner, we think of the song (“

Oh say, can you see…

” ). But the Star-Spangled Banner is a

banner

. It’s the flag of the United States.

Coke and Pep walked hesitantly into a darkened hallway with paintings on the wall and plaques describing how Francis Scott Key, on a boat a few miles from Baltimore harbor, watched (“

by the dawn’s early light

”) the British bombarding Baltimore’s Fort McHenry on September 13, 1814. The attack lasted twenty-five hours, and explosions illuminated (“

the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air

”) a huge American flag, which inspired Key to write the lyrics to his famous song.

The twins turned the corner, into an even darker room. Aside from a dim line of guide lights on the floor, the only thing they could see in the room was the flag. The

real

one. The Star-Spangled Banner that had inspired Francis Scott Key. It was kept in near darkness, to prevent it from fading.

“Wow,” Coke whispered. “This is the real deal.”

It was the largest flag either of them had ever seen—thirty by thirty-four feet—and eight

more

feet of the right side was missing because souvenir hunters had cut off pieces over the years. One of the fifteen stars had been snipped out too. Now the flag was under glass, laid out on a tilted floor, with the lyrics to “The Star-Spangled Banner” on the wall behind it in white, glowing letters.

“Do you think somebody is supposed to meet us in here?” Pep asked. “I can’t see anybody.”

“I can barely see my hand in front of my face,” Coke replied.

“Let’s get out of here,” Pep said. “It’s scary.”

But Coke did see one other thing in the dark room—a piece of paper on the floor in front of the display case. He stooped down to pick it up. The twins rushed out the opposite side of the dark room so they could read it…

“Greensboro lunch counter!” Pep shouted.

They dashed out of the Star-Spangled Banner exhibit and looked to the right. Down the hall was a sculpture of George Washington wrapped in a cloth and holding one hand up in the air. They looked down the hall to the left to see…

A lunch counter!

“This way!” Coke said, and they ran over there.

It was a pretty ordinary-looking lunch counter, with two pink and two green stools. But history was made at that lunch counter.

It was at a Woolworth’s store in Greensboro, North Carolina. Back in 1960, only white people were allowed to eat in the store. But on February 1 of that year, four black college students sat down and asked to be served. When they were told to leave, they refused. They came back the next day too, with more students from the university.

Word got around, and soon black students in fifty-four cities were holding “sit-ins” at segregated lunch counters all over the country. That drew media attention, and within six months Woolworth’s and other stores had opened their lunch counters to anyone who wanted to eat there. It would be another four years until the Civil Rights Act was passed, ending segregation in public accommodations and employment.