New York at War (7 page)

Authors: Steven H. Jaffe

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #United States

In the end, it was the decades-long decimation of their populations by contagious diseases contracted from the Europeans, more even than war, that spelled the downfall of Greater New York’s native peoples. Their decline was most timely for Peter Stuyvesant, who found himself obliged to turn and face other threats to New Netherland’s very existence.

47

CHAPTER 2

Trojan Horses

New Amsterdam and the

English Threat, 1653–1674

P

eter Stuyvesant probably viewed the scene with grim satisfaction, or at least some relief. Stretching almost half a mile from river to river at a height of nine feet, the new wooden wall cut clean across Manhattan Island, separating the bustling town to its south from the meadows and woods to the north, terrain where an enemy army might well gather to launch an attack. It was July 1653, two years before the outbreak of the Peach War, and the people of New Amsterdam nervously awaited the arrival of an English invasion force intent on besieging and conquering their town. When that enemy army materialized, it would now face a continuous wooden barrier, a rallying point from behind which the soldiers and citizens of New Amsterdam could defend their homes and the honor of the Dutch Republic.

The oak planks of the wall, while undoubtedly reassuring, were a far cry from the formidable stone bastions and earthworks Dutch cities built to encircle and protect their populations. When Stuyvesant and city officials had first proposed the wall, they had envisioned a palisade of stout vertical posts hewn from tree trunks. But when they solicited bids from the townspeople, none were willing to provide the posts at a cost the authorities felt the city could afford. Neither fear of attack nor a sense of public duty could persuade the bidders to accept fewer guilders than they asked for. So the wall, ultimately built out of thinner and cheaper plank wood, left something to be desired from the start.

The erection of the wall had been spurred by alarming rumors that had arrived to trouble the eight hundred inhabitants of the port that spring. Travelers reported “warlike preparations” in New England, which seemed linked to the recent outbreak of war between England and the Netherlands. While the English and Dutch nations shared a commitment to Protestantism, their mutual interest in trade produced bitter rivalry on the high seas and led to the outbreak of the Anglo-Dutch War in 1652. The conflict mobilized long-simmering resentments and suspicions on both sides. “The English are a villainous people, and would sell their own fathers for servants in the islands,” New Netherland’s David de Vries once complained. “I think the Devil shits Dutchmen,” snorted a seventeenth-century English statesman. The people of New Amsterdam had long sustained amicable trade relations with the colonists of New England, and Stuyvesant himself behaved cordially toward selected English acquaintances and correspondents. But the Dutch settlers could hardly forget that the national loyalty and territorial ambitions of the New Englanders might override neighborliness, especially now that Puritans—many of whom had fled to the New World to free themselves from the critical scrutiny of the Crown and the Anglican Church—had overthrown the English monarchy and ruled on both sides of the Atlantic. By August 1652, WIC headquarters in Amsterdam was instructing Stuyvesant to “arm all freemen, soldiers and sailors and fit them for defense.”

1

Fearing a possible combined attack by fleets and armies raised in both Old and New England, the people of New Amsterdam tried to prepare for the worst—but they did so armed with new rights and privileges. In February 1653, the townsmen had gained something for which they had long been clamoring and which the WIC finally agreed to grant them: a full-fledged municipal government of two burgomasters (mayors) and five

schepens

(aldermen), authorized to govern “this new and growing city of New Amsterdam” independently. Stuyvesant and his own hand-picked provincial council of three advisors still ruled the entire colony of New Netherland in the company’s name, and the four of them actually had final say as to who would be appointed to serve as burgomasters and

schepens.

But they now had to contend with a municipal government whose members expected certain privileges for the town and were willing to fight Stuyvesant for them.

2

Faced with the English threat, negotiations between the new city magistrates and Stuyvesant—part tug-of-war, part horse trade—immediately focused on defense. Each side tried to get the other to bear the largest possible share of the expenses. But in the process of arguing over preparations for war, New York’s first city government began to define its duties and forged a functioning if combative relationship with the overarching colonial administration.

Stuyvesant and the burgomasters found a way to cooperate to bolster the defenses of the town perched on the southern tip of Manhattan Island. In order to repair and strengthen the fort as a stronghold against English aggression, and to build the wall across the island to prevent an attack from the rear, the city magistrates agreed to raise 6,000 guilders by immediately borrowing the sum from New Amsterdam’s forty-three most prosperous merchants, who would be repaid with interest out of the proceeds of a general tax to be imposed on the city population. In this way, the necessity for military defense inspired New York City’s first experience with deficit spending as well as its first tax assessment. The city government and Stuyvesant also jointly imposed mandatory labor on all able-bodied townsmen, who were divided into four “divisions” that toiled for three-day shifts in rotation until defense work was completed. The town’s carpenters prepared the wall’s planks and rails, while soldiers, enslaved Africans, and free blacks erected a new parapet for the fort. Farmers hauled turf to build up earthworks, mariners fetched wood and stone from nearby forests and quarries in their sloops, and other townsmen sawed boards for gun carriages. However much they might begrudge such labors, the threat of invasion compelled occupants to cooperate in fortifying their city.

3

Had the citizens of New Amsterdam been able to read Oliver Cromwell’s mind, they would either have frantically redoubled their efforts or have dropped their shovels and saws in despair. For England’s Lord Protector and dictator, immersed in his maritime war against the Dutch, had his eye on their island settlement. When he communicated his desires to his colonial governors in February 1654, nearly a year after rumors of New England belligerence first reached New Netherland, his message was decisive. Given the “unneighbourly and unchristian” behavior that Cromwell ascribed to the Dutch settlers, he urged New Englanders to vanquish the Dutch once and for all. In order to accomplish this, Cromwell notified the governors that he was dispatching a fleet of naval vessels with troops and ammunition to Boston, where his officers would coordinate a campaign “for gaining the Manhattoes or other places under the power of the Dutch.” Upon conquering Manhattan and the surrounding hinterland, Cromwell insisted, the Old and New English forces should “not use cruelty to the inhabitants, but encourage those that are willing to remain under the English government, and give liberty to others to transport themselves to Europe.”

4

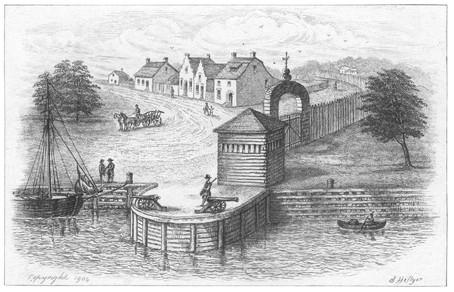

The defensive wall of 1653 at the East River shore, as imagined by an early-twentieth-century artist. Engraving by Samuel Hollyer, 1904. COURTESY OF THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY,

WWW.NYPL.ORG

.

Cromwell’s vision came close to being fulfilled. Four warships carrying some eight hundred men (a force equivalent to New Amsterdam’s total population) left England at the end of February, but a winter storm on the Atlantic drove them off course. In June the ships straggled into Boston harbor, where Cromwell’s commissioned officers, Robert Sedgwick and John Leveret, set about the task of organizing New England’s military forces to augment the planned attack on New Amsterdam. The governors of Connecticut and New Haven Colony, long angered by Dutch claims to western Connecticut, offered to raise hundreds of additional troops. But now things started to unravel. Massachusetts and Plymouth Colony dragged their feet. Lacking a common border with the Dutch to inflame tensions, these two colonies had long enjoyed profitable trade connections with the ship captains and merchants of New Netherland, exchanging fish, salted meat, and lumber for the sugar, molasses, and tobacco carried by Dutch sloops and coast-hugging galliots. Indeed, two of Plymouth’s most esteemed settlers, Thomas Willett and

Mayflower

passenger Isaac Allerton, had relocated to Manhattan Island.

In the end, Massachusetts officials concluded that “they had not a just call for such a work” as an attack on New Amsterdam. By the time it dawned on Sedgwick and Leveret that New England’s Puritans could not be counted on to mount a united front against the Dutch, news arrived from Europe that the Anglo-Dutch War had ended with an English victory. With eight hundred armed men on his hands, Sedgwick decided to sail north rather than south. His troops captured Fort St. John and Fort Royal from the French, thereby creating an English foothold on the coast of Nova Scotia, rather than reducing the Dutch of Manhattan Island. Only in mid-July did a ship arrive from Amsterdam with “tidings of peace,” as Stuyvesant put it, “to the joy of us all.”

5

New Amsterdam had escaped this time, but just barely. Had Leveret and Sedgwick decided to launch an amphibious assault on Manhattan, their sailors, troops, and cannon would easily have vanquished the small garrison of several dozen soldiers manning Fort Amsterdam, even without reinforcements from Massachusetts and Plymouth. The Dutch colony’s new wooden wall would have been breached with little difficulty.

Peter Stuyvesant’s awareness of a persistent English ambition to wipe the Dutch West India Company off the map of North America overshadowed his entire tenure as director-general of New Netherland. Indeed, the possibility of invasion colored the day-to-day life of most of the inhabitants of the bustling little port town that now called itself “the City of New Amsterdam.” As with other elements in the city’s military history, moreover, the wall he built would leave its mark on the world in a way its builders never anticipated. For the dirt path running along its base, where the soldiers and militiamen of New Amsterdam mustered to guard the outer perimeter of their settlement, would one day be known as Wall Street. In future, paper currency and securities would come to replace oak planks as its preferred instruments of defense.

6

Peter Stuyvesant’s preoccupation with defense was not merely a product of local and international circumstances, for the director-general considered himself a soldier above all else. Stuyvesant was a man made by war. His most distinctive physical trait—the wooden, silver-banded peg leg on which he hobbled around New Amsterdam—was a souvenir of the moment that had brought him front and center to the attention of his employers, the Dutch West India Company. As acting director for the WIC on the island of Curacao in 1644, Stuyvesant led troops in an assault aimed at conquering the nearby Spanish island of St. Martin. A Spanish cannonball shattered his right leg, which was amputated below the knee. Before the siege of St. Martin, which ultimately failed, Stuyvesant had been a restless but obscure company bureaucrat with some military training, the college-educated son of a Calvinist minister from the province of Friesland in the northern Netherlands. After the battle, he was known as a bold and decisive soldier.

7

Sent to New Amsterdam to replace the hapless Willem Kieft following the disastrous war against the Lenape, Stuyvesant found the colony in disarray. Upon arriving at Fort Amsterdam in May 1647, the new director announced to the inhabitants that “I shall govern you as a father his children, for the advantage of the chartered West India Company, and these burghers, and this land.” But if the director-general assumed that the freewheeling townspeople of New Amsterdam would obey him like youngsters complying with their father’s orders, or troops following their general, they were happy to disabuse him of his illusions. Wearied by war and hungry for traditional Dutch political privileges the company denied them, settlers were soon engaged in angry confrontations with an autocratic governor whose short temper matched their own. Townspeople derided their new ruler as a “peacock,” a “vulture,” an “obstinate vagabond,” a martinet who stormed about like “the Grand Duke of Muscovy,” and who raged so violently at his subjects “that the froth hung from his beard.” Stuyvesant in turn blasted his critics as “clowns,” “bear-skinners,” and “vile monsters.” If any misguided colonist dared to appeal his rulings to company headquarters in Amsterdam, Stuyvesant warned, “I will make him a foot shorter, and send the pieces to Holland, and let him appeal in that way.” But despite his vitriol, Stuyvesant was an able and intelligent administrator. On his watch the town began to acquire the trappings of a true city, including a wharf on the East River that gave the port a sheltered harbor, fire wardens who inspected hearths and chimneys to prevent conflagrations, and a court to oversee the financial affairs of the colony’s orphans, including those who had lost parents to Indian attacks in Kieft’s War.

8