Ngaio Marsh Her Life in Crime (28 page)

Read Ngaio Marsh Her Life in Crime Online

Authors: Joanne Drayton

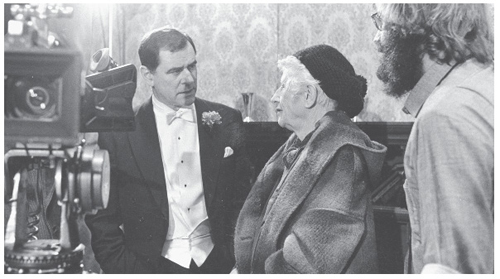

Ngaio Marsh with George Baker in the role of Chief Detective Inspector Alleyn on the set of

Vintage Murder, 1977 ATL

, PAColl-0957-01

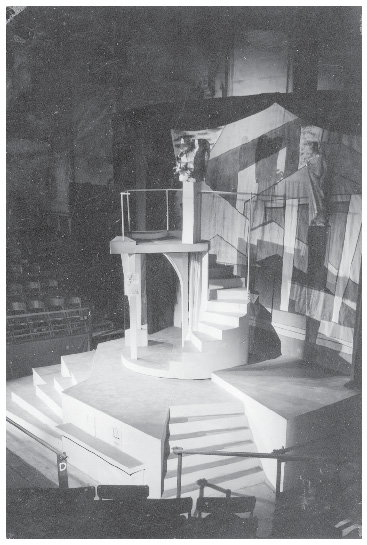

Set designed by Tom Taylor for

Julius Caesar

produced in the Great Hall of Canterbury University College, Christchurch, 1953. Collection of Annette Facer

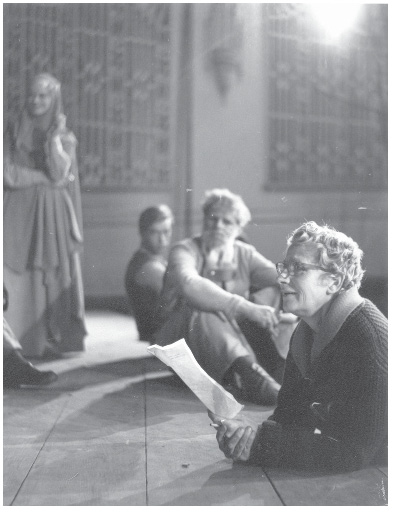

A quiet moment for Ngaio while directing. Collection of Annette Facer

Ngaio and Gerald Lascelles in rehearsals for the inaugural production of

Twelfth Night

at the Ngaio Marsh Theatre, Christchurch, 1967. Collection of Annette Facer

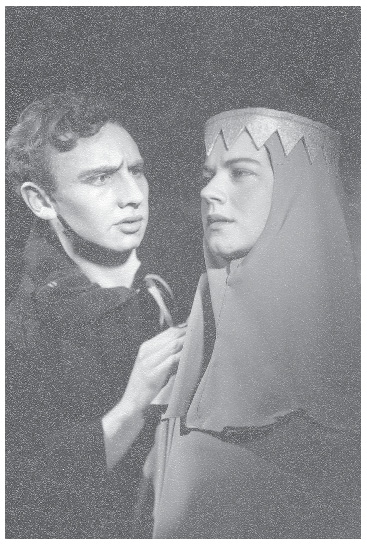

David Hindin (Earl of Kent) and Annette Facer (Cordelia) in

King Lear,

1956. Collection of Annette Facer

Ngaio directing

King Lear,

with Annette Facer, David Hindin, and Mervyn Glue (Lear) in the background. Collection of Annette Facer

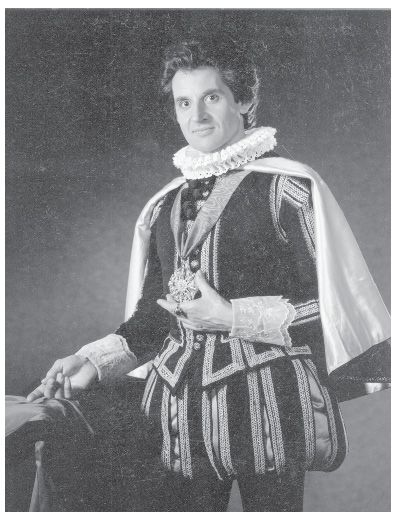

Jonathan Elsom in

Sweet Mr Shakespeare,

1975. He also wore this costume as Chorus in

Henry V,

1972. Collection of Jonathan Elsom

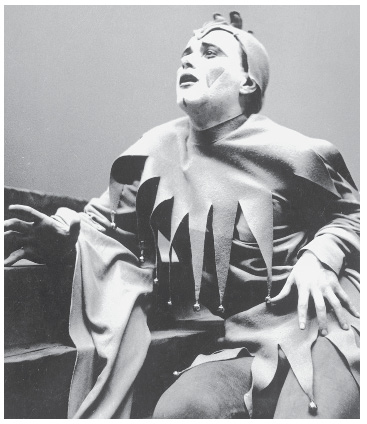

Elric Hooper as the Fool in

King Lear,

1956.

ATL, PA

Coll-0285-1-042

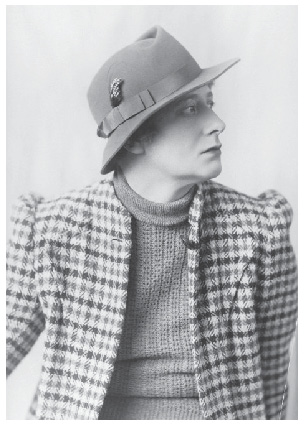

Ngaio, 15 April 1936. atl, ½-046800-f

Sylvia Fox, c. 1930. Collection of Richard and Ginx Fox

Ngaio in the 1940s, atl, ½-144512-f

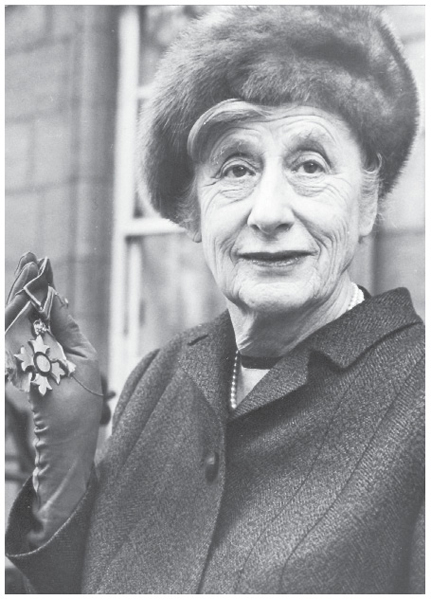

Dame Ngaio Marsh, Buckingham Palace, 1966. St Margaret’s College (SMC 1-4e)

The Marsh Million Murders

A

lmost as soon as she stepped off the boat, Billy Collins threw a massive cocktail party to celebrate Ngaio’s amazing success. It was July 1949, and, in conjunction with Penguin Books, Collins released 10 of her novels simultaneously, with a print run of 100,000 copies per title: a million books by Ngaio Marsh came onto the international market. The only other writers given this distinction were George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells and Agatha Christie.

As she stood elegantly sipping her drink, Ngaio knew she had made it. She had come fresh from the Antipodes to England to discover she was a star. The experience was like slipping through the back of the wardrobe in Narnia, into another world, a world that appreciated her as a writer. ‘So it was astonishing, this time in England,’ she wrote reflectively in

Black Beech,

‘to find myself broadcasting and being televised and interviewed and it was pleasant to find detective fiction being discussed as a tolerable form of reading by people whose opinion one valued.’ She was fêted for something that was almost an embarrassment in New Zealand.

I am always asked

to write articles saying what I think about [the theatre]

now

and even, on exceptional occasions, what I think about William Shakespeare,

but seldom what I think about crime stories…Intellectual New Zealand friends tactfully avoid all mention of my published work and if they like me, do so, I cannot but feel, in spite of it.

So far as Collins was concerned, Ngaio had become an industry. Back in 1943, the publisher had brokered a deal with the Doubleday Dollar Book Club, which had chosen

Colour Scheme

as its December selection. In a memo to Ngaio, Collins explained: ‘

They guarantee 175,000 copies

and pay $8,750, which will be split between Little Brown and the author.’

Billy Collins was a personal friend as well as a business associate, and the pair exchanged regular letters, always with warmth. He admired her writing, and delighted in promoting her books. ‘

I have read your new MS

Died in the Wool

and enjoyed it immensely,’ he had told her in August 1944.

We are planning to publish in January 1945, with the biggest first edition we have yet printed of your books. We will probably be printing it in Canada at the same time, to fit in with the American edition…I do not expect you have any plans yet for after the war but I wonder if there is any chance of your coming over here. I hope there is.

He had ended with a startling piece of news: ‘Our Pall Mall office was bombed earlier in this year and this is our temporary office.’ All records relating to Collins’s publication of Ngaio’s and Agatha Christie’s books were destroyed in the air raid. Ngaio had responded, in October:

Here in New Zealand

we feel almost apologetic about our immunity from air raids. Your laconic sentence about your own offices in Pall Mall having gone is typical of so many English letters. One usually regrets very sincerely that one has not been there during the last four cataclysmic years. I hope very much to get home before long, but as you probably know, all permits to travel have been refused since the war.

Now Ngaio was finally here, but the London she returned to was bomb-scarred and depressed. She felt a difference in the people. There was an acquiescence she had never seen before. The wild inter-war period, with its theatre traffic and riotous night-life, had all but gone, to be replaced by tiredness and indifference.

The BBC chased her for an interview, which was broadcast in September 1949. What were her impressions of post-war London? What could she say, she responded, but that something was missing in the theatre she saw, and in the city’s streets? Her rich, velvety voice faltered when she came to the final words of her ‘London Revisited’:

What can a New Zealander

have the cheek to say about the wastelands behind St Paul’s? Only that one turns away from them with a kind of astonishment that a people who suffered this nightmare outrage should be as they are, in good heart after all. What an impertinence to say that one finds them a ‘little tired’.

In the midst of the rubble and rationing, Ngaio was experiencing the glamour of celebrity, as the launch of her ‘Marsh Million’ was accompanied by a massive marketing drive. Howard Haycraft, in his seminal book

Murder for Pleasure: The life and times of the detective story,

published in 1942, estimated that in the United States at the beginning of the 1940s ‘the average sale of the ordinary crime novel—as nearly as may be gauged from the cautious statements of the publishers—lies somewhere between 1,500 and 2,000 copies’. Best-sellers were rare, he claimed, and the greatest to date were those of S.S. Van Dine who

‘averaged

only 30,000 copies per title’. But he was an exception. ‘

An entire year may pass

in which no crime story tops the 10,000 mark.’ He estimated ‘that a maximum of 600,000 new copies are

sold

in the United States yearly’, and that the whole detective writing industry grossed ‘little more than a million dollars’ annually. In Britain, less than a decade later, Collins and Penguin were releasing a million books by just one author. It was a calculated risk, but still a risk. The distribution and marketing implications were huge. Ngaio was obliged to assist Collins in every way she could.

There were radio and newspaper interviews, and now even television, which had been commercially obtainable in Britain from the late 1930s and by 1950 was widely available. In New Zealand, radio still reigned, so when Ngaio was invited to appear as a guest on BBC television shows it was a novel experience. But radio remained her

métier.

She broadcast on the Home and World Services and on Light Programmes. She spoke with a precision and allure that challenged any BBC voice, and her sometimes sycophantic colonial sentiments were balm to a wounded empire. During her 20-month stay in Britain she was involved

in radio programmes like

Talk Yourself Out of This, Woman’s Hour

and

London West Central.

She was a quick-witted, humorous and popular guest, but she was also something more. Ngaio represented nostalgia in a post-war limbo period before Britain found its feet. The colonial that she was, the Golden Age of the detective novel that she was part of: both belonged to a pre-war era. She could talk convincingly of Britain as ‘Home’, and people still avidly read her books, but change was in the air.

It was a tremendous asset that, at heart, Ngaio, although a shy and private person, was a natural performer. Collins knew they could put her in any public situation and she would attract the right kind of attention. Agatha Christie was much more reclusive and found public exposure an ordeal. In public, in England, Ngaio was glamorous and fashionably dressed; there was a gorgeous sealskin coat for which she was renowned. She still had the elegant mannequin’s figure of her early years in London, and could carry off exquisitely cut long skirts, hats, bags and high-heeled shoes. Her

pièce de résistance

of dazzling eccentricity was to walk through Knightsbridge with her Siamese cat Ptolemy in a blue jewelled collar on a lead. She loved cats, and in London she acquired Ptolemy as a kitten. Because there was not much room in her small flat, she exercised him in the street. Tastefully dressed and walking together, Ptolemy and Ngaio turned heads.

Another equally attention-grabbing purchase was Ngaio’s cream Mark V Jaguar. She bought it almost immediately after she arrived in London, and took it back to New Zealand when she returned. In a world of shortages and rationing, it was a breathtaking piece of extravagance. Ngaio loved driving fast cars and this was the opportunity to indulge her passion. She was conscious of status symbols and image, but this social awareness was tempered by her puritanical upbringing. Her indulgences were never absolutely excessive, and she was always very generous with her possessions. Numerous people drove her car, including young John and Bear Mannings, and she often reached into her own pocket to help friends. And suddenly money was there in bigger amounts than ever before. The shops were full of Marsh novels and the cash registers rang.

But British post-war taxes were inordinately high. Britain used its people on the battlefields of the Second World War, and when the killing ended they were used again to make good the nation’s debt. Ngaio was taxed under these conditions, so what could have been a vast income was dramatically reduced. Terry Coleman quotes taxation figures related to incomes of Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh, which demonstrate the huge increase. The standard rate of

income tax in 1939 was 22.75 per cent; by 1940 this had risen to 35 per cent, and to 50 per cent by 1945. Income tax on the first £2,000 earned was set at 50 per cent, and after that a surtax was added: the highest rate possible was ‘

an absurd 97.5 per cent

’. Ngaio also faced further levies in New Zealand. Not long before he died, Ngaio’s father calculated that on some of her income she was paying ‘

one pound and seven pence

in income tax for every pound earned’. But she loved nice things, fine food and a life edged with flamboyance, and this was expensive to maintain in Britain, so the incentive to keep writing remained.

Ngaio fiercely protected her private life, away from the media and the streets of Knightsbridge. For much of her time in London she lived with Pamela Mann in an unfurnished flat above a clock shop. ‘

[We] are sharing this flat

with two New Zealanders—Elizabeth & Bob Stead,’ she wrote to friends in Christchurch. Bob Stead was attending The Old Vic with five other ‘ex-student-players’. ‘We like our flat & our Georgian street so much that we want all of you to hurry Home & visit us. I’m writing hard & doing quite a bit of Broadcasting.’ The address was 56 Beauchamp Place, just a few doors down from the second Touch and Go shop she and Nelly Rhodes had taken 20 years before. It was

déjà vu,

but now she was a successful author.

Her nights were alive with the sound of clocks from below. ‘

I could hear minuscule

chimes, single tinkling bells, a gong, musical-box confections and the punctual wheelhorses observations of a dependable grandfather. There was a French clock that tootled a little silver trumpet.’ London was a fantasy world for Ngaio, and her imagination was caught up again in its history and literature. ‘It was like the setting for a Victorian fairy-tale’ she said of the nights she lay awake in her flat, picturing the clocks below. She bought food from Harrod’s around the corner, but the flat was furnished ‘from junk picked up in or near Fulham Road’. Ngaio loved luxuries, but she was a pragmatist when it came to life’s rudiments. When she wanted extravagance there were the fashionable shops of Brompton Road and Sloane Street, and the busy markets. After 12 long years away she was thrilled to be back.

Pamela Mann was an ideal companion for Ngaio, who delighted in showing her the wonders of London. She bought her a smart imitation ocelot coat, elegant armoury against the chill of London’s winter. Together they attended theatre in quantities that could be described as compulsive. They both kept a record of the shows attended, and Ngaio pasted each programme into her scrapbook, commenting on all the productions and ranking them. Between July 1949, when

she arrived, and September 1950, when she stopped keeping a record, Ngaio saw ‘

sixty-two productions

, sometimes two a day’. Although Mann was a student player, one of Ngaio’s prot

é

g

é

s, it was her attendance at Ngaio’s production courses that probably began their intimate association.

In 1947 Ngaio had run production workshops at Canterbury College and, in January 1948, a Theatrical Production residential workshop at Wallis House in Lower Hutt. At the summer school Ngaio was the ‘

director and instructor

in production’, actor and voice teacher Maria Dronke taught ‘speech craft’, and Sam Marsh Williams ‘décor’ design. Pamela Mann was one of many promising Canterbury College students, including Brigid Lenihan and Bernard Kearns, who attended these workshops. Lenihan dazzled everyone at breakfast on the first morning at Wallis House. ‘

She was late

and she made her entrance down a big staircase. She filled the room,’ according to artist and drama tutor Rodney Kennedy. Mann, less ostentatious, steady, intelligent and interested in the production side of theatre, appealed to Ngaio, and they began a close working relationship. Ngaio’s young male stars, who came to stay with her for one-on-one acting instruction, left before the show ended, but Pamela Mann stayed on. Ngaio had status and experience to offer her; Mann had skills a director and writer could use.

Ngaio developed intense emotional bonds with women, and this was one of them. Mann had moved up to Marton Cottage as Ngaio’s live-in secretary until their departure for London. She typed correspondence and manuscripts while Ngaio directed Congreve’s

The Way of the World,

and they went to rehearsals and toured Australia together with the student players. It was an ideal arrangement, and when Mann gained a place in the production course at The Old Vic it seemed the perfect time for them to leave New Zealand. It was Mann who helped Ngaio in Christchurch with

Swing, Brother, Swing

(published in the United States as

A Wreath for Rivera),

which came out in April 1949, and Mann who assisted her to write as much as she could of

Opening Night

before they arrived in London. Mann was with Ngaio through the difficult time of her father’s death, compounded by The Old Vic visit and the disruptions of the Australian tour, which took their toll on her writing.

Swing, Brother, Swing

was a formulaic book. Ngaio fell back on what she knew to produce something that bordered on the hackneyed. The plot is familiar: another death on stage in front of an audience that miraculously includes Chief Detective

Inspector Roderick Alleyn. This time, the setting is one of the jazz nightclubs that filled Ngaio’s early days in London with electrifying colour, although she makes the band’s style more contemporary. The Breezy Bellair’s Boy-band is gimmicky and offbeat like American Spike Jones and His City Slickers, whose radio programmes were broadcast around the world from the mid-1940s. Jones was known for his satirical renditions of popular songs, punctuated by the sound of whistles, bells, Goonish snatches of lyrics, and gunshots. In Breezy Bellair, Ngaio creates a similar iconic band leader and this lively conceit could have created an upbeat piece of writing, but she peoples her nightclub with tired old aristocratic characters.