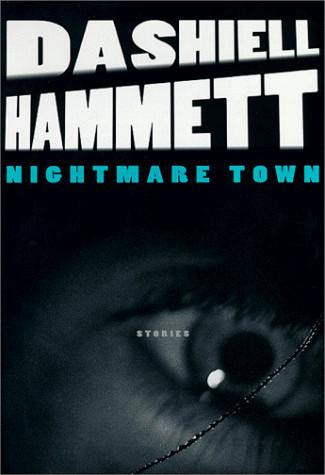

Nightmare Town: Stories

Hammett’s six? The five full-length novels written in the brief period 1929-34, including the universally acknowledged masterpieces

The Maltese

Falcon

and

The Glass Key;

plus a collection (fairly considerable) of short stories, covering a much longer period.

Nightmare Town

presents the reader with twenty of these stories, most of which have been unavailable in print for some time.

In view then of his comparatively limited output, we may reasonably ask if the high praise bestowed on Hammett by Raymond Chandler and Ross Macdonald – his two most distinguished heirs in the ‘hard-boiled’ lineage – was perhaps a little over the top. And to put readers’ minds at rest (there are enough questions to be sorted out in the stories) the answer is ‘decidedly not’. Each of these three writers was practising his craft in a society that was corrupt – with even some of the private eyes potentially corruptible themselves – and in a world that seemed randomly ordained. The advice to fellow writers who were in some doubt about the continuation of a plot was usually ‘Have a man come through the door with a gun!’ and the ubiquity of guns then was a match for that of mobile phones today. Furthermore, as Chandler maintained, murder was committed not just to provide a detective-story writer with a plot. Almost all the sleuths featured in the troubled and often chaotic years between the 1920’s and the 1950’s would have been wholly sceptical about solving a case with the aim of putting the universe back to rights, of restoring some semblance of a moral framework to a temporarily blighted planet. No. They were doing the job they were paid to do, as was Hammett himself in his years working for the Pinkerton Detective Agency, with the resolution (if any) of their cases more the result of chance, of hunches, of experience than of some Sherlockian expertise in Eastern European cigar-wrappings.

It is the last mentioned qualification – that of experience, which gives the Hammett stories their distinctive flavour of authenticity. Yet it would be rather misleading to categorise them, in a wholly general sense, as essays in ‘realistic’ fiction, since Hammett is as liable as most detective-story writers to settle for the reassuringly ‘romantic’ approach that his gritty and usually fearless sleuths are little short of semi-heroic stature.

Who are these men?

First, we meet the unnamed Continental Op, an operative with the ‘Continental Agency’, who in spite of his physical appearance, short and fat, is clearly based on the tall and elegant Hammett himself, with the casework based on Hammett’s personal experiences as a Pinkerton detective. In this selection, we have seven stories featuring the Op, each narrated in a matter-of-fact style in the first person, and each illustrating some aspect of his tenacity and ruthlessness, but affording virtually no biographical information.

Second (and taking Hammett’s first name) is Sam Spade, who features here in

A Man Called Spade, Too Many Have Lived,

and

They Can Only Hang You Once

– the only three stories from the whole corpus in which the memorable hero of

The Maltese Falcon

walks and stalks the streets of San Francisco once again. The narration is in the third person, and as with the Op we are given next to no biographical details that we had not already known. Spade has no wish to solve any erudite riddles; he is a hard and shifty fellow quite capable of looking after himself, thank you; his preoccupation is to do his job and to get the better of the criminals some client has paid him to tangle with.

The third – and for me potentially the most interesting – is a man who appears here, just the once, in

The Assistant Murderer,

introduced as follows in the first sentence:

Gold on the door, edged with black, said ALEXANDER RUSH, PRIVATE DETECTIVE. Inside, an ugly man sat tilted back in a chair, his feet on a yellow desk.

He is a match for the other two – laconic, sceptical, successful; yet I think that Hammett was striking out in something of a new direction with Alec Rush, and I wish that he had been more fully developed elsewhere.

The other stories offer considerable range and variety – not only in locality, but more interestingly in diction and point of view. Take, for instance, the repetitive, virtually unpunctuated narrative of the young boxer (already punch-drunk, we suspect) at the opening of

His Brother’s Keeper:

I knew what a lot of people said about Loney but he was always swell to me. Ever since I remember he was swell to me and I guess I would have liked him just as much even if he had been just somebody else instead of my brother; but I was glad he was not somebody else.

Again, take the psychological study, in

Ruffian’s Wife,

of a timid woman who suddenly comes to the shocking realisation that her husband… But readers must read for themselves.

After reading (and greatly enjoying) these stories, what surprised me most was how Hammett has kept the traditional ‘puzzle’ element alive. The majority of the stories end with some cleverly structured surprise, somewhat reminiscent of O’Henry at his best (see especially, perhaps,

The Second-Story Angel).

But such surprises are not in the style of a pomaded Poirot shepherding his suspects into the library before finally expounding the truth. Much more likely here is that our investigator happens to be seated amid the randomly assembled villains, with a frisson of fear crawling down his back and a loaded revolver pointed at his front.

The secrets of Hammett’s huge success as a crime novelist are hardly secrets at all. They comprise his extraordinary talents for story-telling; for characterisation; and for a literary style that is strikingly innovative.

As a story-teller, he has few equals in the genre. In

Who Killed Bob Teal?,

for example, a suspicious party has flagged down a taxi and the taxi’s number has been recorded. The narrative continues:

Then Dean and I set about tracing the taxi in which Bob Teal had seen the woman ride away. Half an hour in the taxi company’s office gave us the information that she had been driven to a number on Greenwich Street. We went to the Greenwich Street address.

Many of us who have been advised by editors to ‘Get on with the story!’ would have profited greatly from studying such succinct economy of words.

The characterisation of Hammett’s dramatis personae is realised, often vividly, on almost every page here – primarily through the medium of dialogue, secondarily by means of some sharply observed, physical description (especially of the eyes). Such techniques are omnipresent, and require no specific illustration. They are dependent wholly upon the author’s writing skills.

Much has been said about Hammett’s literary style, and critics have invariably commented on its comparative bareness, with dialogue gritty and terse, and with language pared down to its essentials. But such an assessment may tend to suggest ‘barrenness’ of style rather than ‘bareness’ – as if Hammett had been advised that any brief stretch of even palely-purplish prose was suspect, and that almost every adjective and adverb was potentially

otiose.

Yet we need read only a page or two here to recognise that Hammett knew considerably more about the business of writing than any well-intentioned editor.

Consider, for example, the second paragraph of the major story,

Nightmare Town:

A small woman – a girl of twenty in tan flannel – stepped into the street. The wavering Ford missed her by inches, missing her at all only because her backward jump was bird-quick. She caught her lower lip between white teeth, dark eyes flashed annoyance at the passing machine, and she essayed the street again.

Immediately we spot the Hammett ‘economy’ trademark. But something more, too. We may be a little surprised to find such a wealth of happily chosen epithets here (what a splendid coinage is that ‘bird-quick’!) as Hammett paints his small but memorably vivid picture.

This story (from which the book takes its title) shows Hammett at the top of his form, and sets the tone for a collection in which we encounter no sentimentality, with not a clichй in sight, and with none of the crudity of language which (at least for me) disfigures a good deal of present-day American crime fiction.

Here, then, is a book to be read with delight; a book in which we pass through a gallery of bizarre characters (most of them crooks) sketched with an almost wistful cynicism by a writer whom even the great Chandler acknowledged as the master.

COLIN DEXTER

January 2001

Oxford

NOLAN

Nightmare Town,

displaying the full range of Dashiell Hammett’s remarkable talent.

In his famous 1944 essay,

The Simple Art of Murder,

Raymond Chandler openly acknowledged Hammett’s genius. He properly credited him as “the ace performer,” the one writer responsible for the creation and development of the hard-boiled school of literature, the genre’s revolutionary realist. “He took murder out of the Venetian vase and dropped it into the alley,” Chandler declared. “Hammett gave murder back to the kind of people that commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse.”

And crime novelist Ross Macdonald also granted Hammett the number one position in crime literature: “We all came out from under Hammett’s black mask.”

Born in 1894 to a tobacco-farming Maryland family, young Samuel grew up in Baltimore and left school at fourteen to work for the railroad. An outspoken nonconformist, he moved restlessly from job to job: yardman, stevedore, nail-machine operator in a box factory, freight handler, cannery worker, stock brokerage clerk. He chafed under authority and was often fired, or else quit out of boredom. He was looking for “something extra” from life.

In 1915 Hammett answered a blind ad which stated that applicants must have “wide work experience and be free to travel and respond to all situations.” The job itself was not specified.

Intrigued, Hammett found himself at the Baltimore offices of the Pinkerton Detective Agency. For the next seven years, except during periods of army service or illness, Sam Hammett functioned as an agency operative. Unlike most agency detectives, who worked within a single locale, the Pinkerton detectives, based in a variety of cities, ranged the states from east to west, operating across a wide terrain. Thus, Hammett found himself involved in a varied series of cross-country cases, many of them quite dangerous. Along the way, he was clubbed, shot at, and knifed; but, as he summed it up, “I was never bored.”

In 1917 his life changed forever. Working for Pinkerton as a strike-breaker against the International Workers of the World in Butte, Montana, Hammett was offered five thousand dollars to kill union agitator Frank Little. After Hammett bitterly refused, Little was lynched in a crime ascribed to vigilantes. As Lillian Hellman later observed: “This must have been, for Hammett, an abiding horror. I can date [his] belief that he was living in a corrupt society from Little’s murder.” Hammett’s political conscience was formed in Butte. From this point forward, it would permeate his life and work.

In 1918 he left the agency for the first time to enlist in the army, where he was later diagnosed with tuberculosis. (“Guess it runs in the family. My mother had T.B.”) Discharged a year later, he was strong enough to rejoin Pinkerton. Unfortunately, the pernicious disease plagued him for many years and took a fearsome toll on his health.

In 1921, with “bad lungs,” Hammett was sent to a hospital in Tacoma, Washington, where he was attended by Josephine Dolan, an attractive young ward nurse. This unworldly orphan girl found her new patient “handsome and mature.” She admired his military neatness and laughed at all his jokes. Soon they were intimate. Jose (pronounced “Joe’s”) was very serious about their relationship, but to Hammett it was little more than a casual diversion. At this point in his life he was incapable of love and, in fact, mistrusted the word.

He declared in an unpublished sketch: “Our love seemed dependent on not being phrased. It seemed that if [I] said ‘I love you,’ the next instant it would have been a lie.” Hammett maintained this attitude throughout his life. He could write “with love” in a letter, but he was incapable of verbally declaring it.

Finally, with his illness in remission, Hammett moved to San Francisco, where he received a letter from Jose telling him that she was pregnant. Would Sam marry her? He would.

They became husband and wife in the summer of 1921, with Hammett once again employed by Pinkerton. But by the time daughter Mary Jane was born that October, Hammett was experiencing health problems caused by the cold San Francisco fog, which was affecting his weakened lungs.

In February 1922, at age twenty-seven, he left the agency for the last time. A course at Munson’s Business College, a secretarial school, seemed to offer the chance to learn about professional writing. As a Pinkerton agent, Hammett had often been cited for his concise, neatly fashioned case reports. Now it was time to see if he could utilise this latent ability.

By the close of that year he’d made small sales to

The Smart Set

and to a new detective pulp called

The Black Mask.

In December 1922 this magazine printed Hammett’s

The Road Home,

about a detective named Hagedorn who has been hired to chase down a criminal. After leading Hagedorn halfway around the globe, the fugitive offers the detective a share of “one of the richest gem beds in Asia” if he’ll throw in with him. At the story’s climax, heading into the jungle in pursuit of his prey, Hagedorn is thinking about the treasure. The reader is led to believe that the detective is tempted by the offer of riches, and that he will be corrupted when he sees the jewels. Thus, Hammett’s career-long theme of man’s basic corruptibility is prefigured here, in his first crime tale.

In 1923 Hammett created the Continental Op for

The Black Mask

and was selling his fiction at a steady rate. In later years, a reporter asked him for his secret. Hammett shrugged. “I was a detective, so I wrote about detectives.” He added: “All of my characters were based on people I’ve known personally, or known about.”

A second daughter, Josephine Rebecca, was born in May 1926, and Hammett realised that he could not continue to support his family on

Black Mask

sales. He quit prose writing to take a job as advertising manager for a local jeweller at $350 a month. He quickly learned to appreciate the distinctive features of watches and jewelled rings, and was soon writing the store’s weekly newspaper ads. Al Samuels was greatly pleased by his new employee’s ability to generate sales with expertly worded advertising copy. Hammett was “a natural.”

But his tuberculosis surfaced again, and Hammett was forced to leave his job after just five months. He was now receiving 100 percent disability from the Veterans Bureau. During this flare-up he was nearly bedridden, so weak he had to lean on a line of chairs in order to walk between bed and bathroom. Because his tuberculosis was highly contagious, his wife and daughters had to live apart from him.

As Hammett’s health improved, Joseph T. Shaw, the new editor of

Black Mask,

was able to lure him back to the magazine by promising higher rates (up to six cents a word) and offering him “a free creative hand” in developing novel-length material. “Hammett was the leader in what finally brought the magazine its distinctive form,” Shaw declared. “He told his stories with a new kind of compulsion and authenticity. And he was one of the most careful and painstaking workmen I have ever known.”

A two-part novella,

The Big Knockover,

was followed by the

Black Mask

stories that led to his first four published books:

Red Harvest, The Dain Curse, The Maltese Falcon,

and

The Glass Key.

They established Hammett as the nation’s premier writer of detective fiction.

By 1930 he had separated from his family and moved to New York, where he reviewed books for the

Evening Post.

Later that year, at the age of thirty-six, he journeyed back to the West Coast after

The Maltese Falcon

was sold to Hollywood, to develop screen material for Paramount. Hammett cut a dapper figure in the film capital. A sharp, immaculate dresser, he was dubbed “a Hollywood Dream Prince” by one local columnist. Tall, with a trim moustache and a regal bearing, he was also known as a charmer, exuding an air of mature masculinity that made him extremely attractive to women.

It was in Hollywood, late that year, that he met aspiring writer Lillian Hellman and began an intense, volatile, often mutually destructive relationship that lasted, on and off, for the rest of his life. To Hellman, then in her mid-twenties, Hammett was nothing short of spectacular. Hugely successful, he was handsome, mature, well-read, and witty – a combination she found irresistible.

Hammett eventually worked with Hellman on nearly all of her original plays (the exception being

The Searching Wind).

He painstakingly supervised structure, scenes, dialogue, and character, guiding Hellman through several productions. His contributions were enormous, and after Hammett’s death, Hellman never wrote another original play.

In 1934, the period following the publication of

The Thin Man,

Hammett was at the height of his career. On the surface, his novel featuring Nick and Nora Charles was brisk and humorous, and it inspired a host of imitations. At heart, however, the book was about a disillusioned man who had rejected the detective business and no longer saw value in the pursuit of an investigative career.

The parallel between Nick Charles and Hammett was clear; he was about to reject the genre that had made him famous. He had never been comfortable as a mystery writer. Detective stories no longer held appeal for him. (“This hard-boiled stuff is a menace.”)

He wanted to write an original play, followed by what he termed “socially significant novels,” but he never indicated exactly what he had in mind. However, after 1934, no new Hammett fiction was printed during his lifetime. He attempted mainstream novels under several titles:

There Was a Young Man

(1938);

My Brother Felix

(1939);

The Valley Sheep Are Fatter

(1944);

The Hunting Boy

(1949); and

December 1

(1950). In each case the work was aborted after a brief start. His only sizable piece of fiction,

Tulip

(1952) – unfinished at 17,000 words – was printed after his death. It was about a man who could no longer write.

Hammett’s problems were twofold. Having abandoned detective fiction, lie had nothing to put in its place. Even more crippling, he had shut himself down emotionally, erecting an inner wall between himself and his public. He had lost the ability to communicate, to share his emotions. As the years slipped past him, he drank, gambled, womanized, and buried himself in Marxist doctrines. His only creative outlet was his work on Hellman’s plays. There is no question that his input was of tremendous value to her, but it did not satisfy his desire to prove himself as a major novelist.

The abiding irony of Hammett’s career is that he had already produced at least three major novels:

Red Harvest, The Maltese Falcon,

and

The Glass Key

– all classic works respected around the world.

But here, in this collection, we deal with his shorter tales, many of them novella length. They span a wide range, and some are better than others, but each is pure Hammett, and the least of them is marvellously entertaining.

What makes Dashiell Hammett’s work unique in the genre of mystery writing? The answer is: authenticity.

Hammett was able to bring the gritty argot of the streets into print, to realistically portray thugs, hobos, molls, stoolies, gunmen, political bosses, and crooked clients, allowing them to talk and behave on paper as they had talked and behaved during Hammett’s manhunting years. His stint as a working operative with Pinkerton provided a rock-solid base for his fiction. He had pursued murderers, investigated bank swindlers, gathered evidence for criminal trials, shadowed jewel thieves, tangled with safecrackers and holdup men, tracked counterfeiters, been involved in street shoot-outs, exposed forgers and blackmailers, uncovered a missing gold shipment, located a stolen Ferris wheel, and performed as guard, hotel detective, and strikebreaker.

When Hammett sent his characters out to work the mean streets of San Francisco, readers responded to his hard-edged depiction of crime as it actually existed. No other detective-fiction writer of the period could match his kind of reality.

Nightmare Town

takes us back to those early years when Hammett’s talent burned flame-bright, the years when he was writing with force and vigour in a spare, stripped style that matched the intensity of his material. Working mainly in the pages of

Black Mask

(where ten of these present stories were first printed), Hammett launched a new style of detective fiction in America: bitter, tough, and unsentimental, reflecting the violence of the time. The staid English tradition of the tweedy gentleman detective was shattered, and murder bounced from the tea garden to the back alley. The polite British sleuth gave way to a hard-boiled man of action who didn’t mind bending some rules to get the job done, who could hand out punishment and take it, and who often played both sides of the law.

The cynic and the idealist were combined in Hammett’s protagonists: their carefully preserved toughness allowed them to survive. Nobody could bluff them or buy them off. They learned to keep themselves under tight control, moving warily through a dark landscape (Melville’s “appalling ocean”) in which sudden death, duplicity, and corruption were part of the scenery. Nevertheless, they idealistically hoped for a better world and worked toward it. Hammett gave these characters organic life.

Critic Graham Mclnnes finds that “Hammett’s prose… has the polish and meat of an essay by Bacon or a poem by Donne, both of whom also lived in an age of violence and transition.”

The theme of a corrupt society runs like a dark thread through much of Hammett’s work. The title story of this collection, which details a “nightmare” town in which every citizen – from policeman to businessman – is crooked, foreshadows his gangster-ridden saga of Poisonville in

Red Harvest.

(The actual setting for his novel was Butte, Montana, and reflects the corruption Hammett had found there with Frank Little’s death in 1917.)