NIGHTS IN THE GARDENS OF BROOKLYN

Read NIGHTS IN THE GARDENS OF BROOKLYN Online

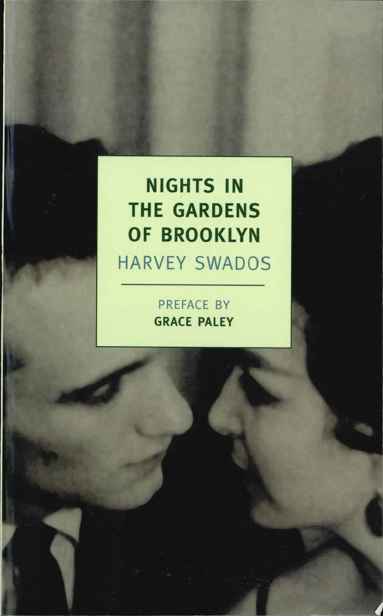

Authors: Harvey Swados

NIGHTS IN THE GARDENS

OF BROOKLYN

HARVEY SWADOS (1920–1972) was born in Buffalo, the son of a doctor. A graduate of the University of Michigan, he served in the Merchant Marine during World War II and published his first novel,

Out Went the Candle

, in 1955. His other books include the novels

Standing Fast

and

Celebration;

a group of stories set in an auto plant,

On the Line

, widely regarded as a classic of the literature of work; and various collections of nonfiction, including

A Radical’s America

. Swados’s 1959 essay for

Esquire

, “Why Resign from the Human Race?,” has often been said to have inspired the formation of the Peace Corps.

GRACE PALEY is a writer and a teacher, a feminist and an activist. Her books include

The Collected Stories; Just as I Thought

, which gathers personal and political essays and articles; and

Begin Again: Collected Poems

. She lives in New York City and Vermont.

Nights in the Gardens

of Brooklyn

The Collected Stories of Harvey Swados

Preface by

Grace Paley

Introduction by

Robin Swados

Copyright © 1951, Harvey Swados

Nights in the Gardens of Brooklyn

A Handful of Ball-points, A Heartful of Love

Where Does Your Music Come From?

N

ights in the gardens of Brooklyn—yes, that’s just the way it was. The boys came home from the war. They were probably men by then but we tended to say “the boys.” If home was New York they would probably live in Brooklyn, at least until they were sure they didn’t want to go west to San Francisco or south to New Orleans, or to some countryside to become a farmer. As in

Nights in the Gardens of Brooklyn

, the girls were waiting. Of course they were probably women by then, but we referred to ourselves and our friends as girls until the women’s movement told us not to and we happily agreed. Before all of us young women and men lay the amazing GI bill, work, and life.

Harvey Swados was born in Buffalo in 1920. He spent four years in the Merchant Marine during the Second World War. Then, maybe looking for Greenwich Village, he settled in Brooklyn for a few unsettling years. He found a job as a census taker, married, moved, had children, wrote wonderful stories, useful, thoughtful essays and reviews, and novels that took a look at life that was different from many of his contemporaries; he taught at Sarah Lawrence and the University of Massachusetts; he went to Nigeria (not many Americans did) to witness the Biafran War. He brought back reports to a mildly disinterested country and a mildly concerned political left, and brought back a friendship with Chinua Achebe—whose work he introduced to many of us. Then when he was only fifty-two he died of an aneurysm. We miss those years of work that never happened, the books that he may have been thinking or dreaming or waiting to do. We miss the straightforwardness in his work and in his person, his generosity and dependability as a literary, political, and personal friend and colleague.

I myself owe him a good deal. He wrote one of the first full reviews of my first book. Only two of the stories had been published previously. I know he had something to do with the offer to me of a teaching job at Sarah Lawrence where, with his help and Jane Cooper’s, I learned the unusual, rigorous methods of radical teaching there.

My office was adjacent to his. In all our talks he seemed to me a New Yorker like myself, one of those who could not imagine NOT living in New York forever. Therefore I was dismayed when he left the city (I admit my parochial views). I knew I’d miss that open-door collegiality. Still, he needed time and money to write. He did, after all, leave to us New Yorkers

Nights in the Gardens of Brooklyn

, a collection about the excitement, success, and failure of my own young age-mates in that lively and confusing postwar world. He left us these stories, unexcelled in accuracy and sympathy.

Who are some of the people in his garden? A young man and would-be dancer, who comes to New York from small-town Ohio and is bewildered by the city’s intensity and fakery, and rediscovers his passion in a tragic act of self-destruction. A young soldier who once idolized his Coney Island uncle but returns from overseas tired and disappointed with the Brooklyn landscape he’d once believed to be paradise; he survives his disappointment by stumbling on empathy. Then there’s also the old woman Marya—a holdout on the third floor of a condemned building on the Lower East Side. In the collection’s title story, Harvey’s alter ego, the story’s narrator, visits her again and again. Much more than one of his census statistics, she seems to tell him something of his own life:

There had been a son and a daughter, but she had survived them both. Now she was on welfare, holed up in an old kitchen, seated at the table in the gloom with the teakettle bubbling away on the chipped old stove. I felt as though I were in a place that was going to last forever. I had some difficulty with the interview, since she knew little English, and I could hardly understand her Yiddish. But it didn’t seem

to make much difference, we took our time, she shuffled back and forth across the kitchen, getting her glasses, steeping the tea, showing me her second papers.

Marya enriches a story of youthful hopefulness and despair as old people often do in literature.

Another collection of stories,

On the Line

, was written—published in any event—in 1957, before

Nights in the Gardens of Brooklyn

. It is about American working people who labor on the American-invented, Ford-created assembly line, and it is a defining work that declares Harvey Swados’s interest in and (like any young socialist) longing for solidarity, if not identity, with those people. Surely his interest in them, which continues in so much of his later work, began in those years, those long days of the nights in Brooklyn, and in the many four- and five-story tenements he walked up and down.

Harvey thought that kind of knowledge should be available to his students. One of them, Liza Ketchum, remembers that she

studied with a wonderful writing teacher named Harvey Swados. He sent us on strange, exciting assignments in New York City. We went to the fish market at dawn and watched the boats come in. We sat on hard benches in Night Court, where people who had been arrested lined up before the judge. We wandered all over the city, taking notes on conversations and soaking up smells, textures, and tastes.

I was actually not crazy about that assignment, maybe because I was a New York kid and had already been properly soaked.

Finally, Harvey was interested in good or almost good women and men more than most writers—and readers. By good people I don’t mean saints or angels, but people who, for all their complexity, want to do the right thing. Luckily he was unsentimental. He had too much integrity to allow for the soft lies of sentiment. At some point in the stories in this collection the world is going to pick up his characters and drop them down. Their innocence—and ours—is going to take a beating. Irving Howe wrote in, I think,

a review of

The Will

, “Harvey was an unfashionable novelist yet his career has been an exemplary one. He is a writer free of public postures, indifferent to literary fads, and totally devoted to perfection of his craft.” Howe repeated these words when he spoke at the University of Massachusetts in 1979 at the dedication when Swados’s papers were deposited in the university archives.

I think it appropriate to follow this short preface with a list of the books Harvey did get to write—in which idealism struggles with despair and in a harsh century sometimes wins.

—G

RACE

P

ALEY

BY HARVEY SWADOS

NOVELS

Out Went the Candle

False Coin

The Will

Standing Fast

Celebration

SHORT STORIES

On the Line

Nights in the Gardens of Brooklyn

A Story for Teddy, and Others

NONFICTION AND ANTHOLOGIES

A Radical’s America

Years of Conscience: The Muckrakers

The American Writer and the Great Depression

A Radical at Large: American Essays

Standing Up for the People: The Life and Works of Estes Kefauver

S

hortly after my father died, I picked up a copy of

A Story for Teddy

—an arbitrary choice from the dozen or so of his books on my shelf—and began scanning its pages for a thread that might connect me to the father I remembered.

I found that thread in the story “Claudine’s Book.” As I read it, I recognized a portrait of myself as a child that my father had drawn. Details had been altered here and there, but the story contained a specific reference to a namesake I had resented in my youth, at a time when friends and foes alike took equal delight in the pleasures of name-calling. I was often teased unmercifully about my name. I was referred to as the one who stole from the rich and gave to the poor, the sidekick of a comic-book hero, and the first bird of spring. I remember angrily asking my father how he had chosen my name, and he replied (not without a certain pride) that I had been named for Robin Roberts, a pitcher for the Philadelphia Phillies. I felt his answer reflected the ultimate indignity, since baseball was a sport in which I had no interest or talent.

Why had he never discussed the story with me before it was published? Perhaps for fear of bruising the sensibility of an already thin-skinned eleven-year-old; or perhaps, in the years that followed, because it simply ceased to exist as a source of discussion, as happens to so many points of contention between parents and children. Whatever the explanation, I long ago put aside any residual childhood resentment—either of my father

or

Robin Roberts—and am left now with only a lingering regret that fate never allowed me the opportunity to thank him adequately for this small but precious legacy.

When my father died on December 11, 1972, at the age of fifty-two,

he left a body of work that is a unique amalgam of politics and fiction. The books span a seventeen-year period from the publication of

Out Went the Candle

, his first novel, in 1955, to the completion of

Celebration

, his last, in 1972; and range from the essays in

A Radical’s America

(1962) to his powerful and now classic portrait of life in an automobile assembly plant,

On the Line

(1957). Two collections of stories published in the 1960s,

Nights in the Gardens of Brooklyn

(1961) and

A Story for Teddy

(1965), are enjoying a renaissance in this volume. They are a distillation of my father’s talents as a fiction writer, and they also display his concerns as an astute observer of the American social scene.

Out of vogue for years, the short story seems to have made a triumphant return in the 1980s. It has undergone transformations that occasionally seem as extreme as the changing political and social forces which have surrounded it. It has been pared down to the bare bone, robbed at times of style and at others, of content. Weary of it all, its characters meander through a romantic and sexual void, vaguely searching for a way to make up for spiritual loss. To underscore their authors’ alienated sensibilities, the stories are typically written in the present tense, as if neither the past nor the future carried any weight. “Hear my story

now,”

these writers cry out. “Yesterday is gone and tomorrow may never come.

In light of this peculiar literary trend, how remarkable it is to encounter in

Nights in the Gardens of Brooklyn

characters whose common bond lies in their resolute refusal to capitulate to emptiness. Their search to find meaning to their lives and their struggle to connect to one another perfectly encapsulate the imagination that spawned them. Filled with a desire for love, dreams of a better life and a more fulfilling job, and driven forward by an often instinctive sense of optimism, these men and women are the products of one man’s creative sensibility—that which belonged to Harvey Swados.

Harvey Swados was born on October 28, 1920, the son of a doctor, in Buffalo, New York. At least until the advent of the Depression, his life was filled with games and music. He and his only sibling, his older sister, Felice (also a writer), spent a great deal of time outdoors; they both played the piano, and he studied the flute as well. But as he once recollected, “throughout the 1930s Buffalo

seemed a gloomy, wretched, and dismal place. There were lengthy evening discussions of young intellectuals dreaming and scheming of fleeing the decaying city.”

My father was fifteen when he left Buffalo and entered the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, and before he reached his eighteenth birthday, he had his first taste of success as a writer: a story published in the university’s quarterly literary review was included in

The Best Short Stories of 1938

. His fervent and lifelong commitment to the politics of the left began at an early age, too. After a brief involvement with the Young Communist League in the thirties, he chose finally and irrevocably to identify himself as a radical socialist.

Several years ahead of him at the University of Michigan was Arthur Miller, one of the few among his contemporaries to exhibit many of the same political and social concerns in his play-writing that my father did in his fiction. In addition to the writers and actors and musicians who populate the stories in this volume, there are salesmen and census-takers, ordinary and decent men who might very well have joined Willy Loman for a cup of coffee in the Automat—Bern in the whimsical “A Handful of Ballpoints, A Heartful of Love”; the reflective narrator of “Nights in the Gardens of Brooklyn”; “The Dancer”’s Peter Chifley, wide-eyed and running desperately from door to door, clutching his Matso Minute Man’s kit. These are the people with whom my father’s sympathies lay—people who work.

And my father worked, always. After graduating in 1940, he took a job in an aircraft plant as a riveter. After a year of that, he was sure he never wanted to live in Buffalo again, and indeed he never did. Nevertheless, the city frequently served as the locale for much of his fiction, most particularly and effectively in his 1963 novel,

The Will

.

In New York, he spent a year working in an aircraft plant in Long Island City, and, fairly well cured of whatever romantic notions he had about the industrial working class, joined the world of seafaring workers at the outset of World War II by enlisting in the Merchant Marine. After training first as a seaman and then as a radio operator, he served as radio officer on a number of ships through 1945, sailing the North Atlantic, the South

Pacific, the Mediterranean and the Caribbean to various ports from Australia to Yugoslavia. His experiences during those years formed the basis for a number of his short stories—“Bobby Shafter’s Gone to Sea,” “Tease,” and “The Letters”—and in a general way were responsible for the marvelous variety of their locales. He also completed an unpublished novel during this period,

The Unknown Constellations

. Resoundingly autobiographical, its story involves a young sailor who settles in New Orleans in the hope of escaping his father’s stern and unforgiving shadow, only to become embroiled in a battle of good versus evil with another authority figure—his crooked boss.

At the war’s end, two of the most profound experiences of my father’s life occurred. His sister, Felice, had published one novel and was at work on another when she died in 1945 at the age of 29. This event devastated him, but it also strengthened his resolve to become a writer.

And in September of 1946, he married my mother Bette.

As marriages go (and many of them went, in the sixties and seventies), it was a long and happy one—always faithful, occasionally turbulent, honest, passionate, and loving. Through it all, my mother remained, in Dan Wakefield’s words, my father’s “best and most trusted editor, literary confidante and counselor, sometime agent, staunchest supporter, shrewdest and most articulate defender of the man and his work, finest and most faithful friend.”

As a child of this extraordinary bond, I was always deeply (if subliminally) cognizant of the frequent instances of public indifference or critical disdain for my father’s work, a situation he acknowledged bluntly during the mid-sixties:

Despite the honors that have come my way in the form of grants, fellowships, and awards, I have never been able to support my family solely from my writing. My books have never sold; and I am sharply aware that my work is seldom considered in critical evaluations of what is presumed best in contemporary American fiction. Nevertheless, on balance, when I consider the miseries of those of my fellow writers who have been treated more like movie stars than creative figures, and whose work has suffered correspondingly, I

incline to the belief that my position is more fortunate than theirs.… I am concerned with pleasing myself, not with gratifying that vast and shapeless public which consumes not the work of novelists, but news about them in slick magazines and gossip columns, as it does candy bars. I remain a social radical, too, at once dismayed and exhilarated by my seemingly doomed yet endlessly optimistic native land.

But if my father was distressed by his lack of commercial success, he certainly never voiced this concern to me; on the contrary, I was oblivious to the financial problems that so often characterize the life of a serious writer. As I grew up, the grants, fellowships, and awards bestowed upon my father—and the occasional sabbaticals he was able to take—led to prolonged and peripatetic stretches of time spent in a variety of homes. Over the years, “home” became something of a generic term to us, comprising Valley Cottage, a small town in Rockland County, New York; San Francisco; Iowa City; Cagnes-sur-Mer, a tiny medieval village nestled in the hills between Nice and Cannes; and finally, a white clapboard house high atop a Berkshire mountain ridge in Chesterfield, Massachusetts, the quiet New England town to which my parents moved just one year before my father’s death.

Our three sojourns to Cagnes in the fifties and sixties were particularly happy times for my family. We were ensconced on the Mediterranean coast and surrounded by a new and very different set of friends and acquaintances—peasants and artists, American expatriates, Scandinavians, British aristocrats both current and fallen. But the culture shock, however mild, led to certain frictions. In particular, it wasn’t an easy move for my mother, who had never been out of the country and spoke no French.

In “Year of Grace,” a frightened and generally inexperienced small-town woman whose stuffy academic husband has transported her abroad during a year’s sabbatical, discovers, unexpectedly and without a trace of vindictiveness, that there is more to her life than her connection to her husband. Predating the women’s movement by more than a decade, this unstrident portrayal of self-discovery appears as valid today as it did twenty-five years ago. It seems perfectly apropos that it is followed by what might

be considered its Gallic counterpart, “The Peacocks of Avignon.” This brief but deeply moving piece tells the story of a young woman whose sorrow and resentment threaten to destroy her otherwise loving relationship with her mother, a widow desperate to make up for the loss of her husband—and her youth—by engaging in an affair with a man half her age. Alone in a foreign country, she discovers, in a sudden and profound moment of revelation, the meaning of forgiveness.

Although my family spent more than five years in Europe, it was the “seemingly doomed yet endlessly optimistic native land” to which my father always insisted we return. It was America—a country whose political and social mores served as the target for much of his disapprobation—for which he retained his greatest loyalty and deepest affection. It was here that he found his true voice—a voice that spoke out for the great American values, values he felt were all too often perilously ignored by his fellow citizens.

He was often ahead of his time. His 1959 essay in

Esquire

, “Why Resign from the Human Race?,” provoked an unprecedented avalanche of mail and is generally acknowledged to have inspired the formation of the Peace Corps. His social concerns were no less apparent in his stories. For example, in “A Chance Encounter,” the issue of abortion, possibly more controversial today than when the story was written, produces a surprising and most unexpected victim. Peopled almost exclusively by male characters, it is a subtle, shrewd, and thought-provoking argument for freedom of choice.

My father gracefully balanced the larger social and political concerns in his novels and essays with a tender humanism in his stories. The subject of poverty, for example, plays a devastating role in “A Question of Loneliness,” in which an overburdened and underpaid young worker winds up paying dearly for his solitary attempt to rescue his wife from the dreariness of her domestic routine. The cost to him is a future of guilt and recrimination. Their story is sad and chilling.

“Nights in the Gardens of Brooklyn” also presents young people striving to ameliorate their lot in a difficult world, but it takes a far broader and more optimistic (albeit cynical) view of its impoverished group of protagonists. It is a brilliant and stirring novella which might well have served as the progenitor for his long novel,

Standing Fast

, published in 1970. The product of five years of work, the novel chronicles in painstaking detail the history of the American left between 1939 and 1963.

“Nights in the Gardens of Brooklyn,” much like the later novel, examines people from a variety of social, political, and economic backgrounds whose lives intertwine. Their early ideals will inevitably and even brutally be compromised with the passage of time. The story will seem all the more touching and timely to a new generation of readers whose lives bridged the gap between the turbulent and idealistic sixties and the radically different—and markedly un-radical—eighties. Little has changed in our entry into the rat race; only the price has gone up. One of the most beautiful of all New York stories, “Nights in the Gardens of Brooklyn” remains a perfectly compressed portrait not only of the generation of young people struggling to find their way immediately following World War II, but also of what is arguably the world’s most exciting city, so joyously described in the opening sentence as “my mother, my mistress, my Mecca.”