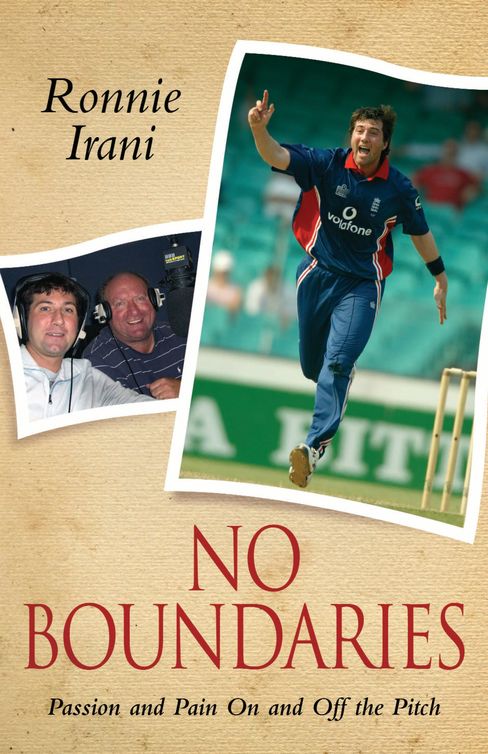

No Boundaries

Authors: Ronnie Irani

Passion and Pain On and Off the Pitch

Ronnie Irani

with Richard Coomber

I would like to take this opportunity to thank my wife Lorraine for just allowing me to be Ronnie Irani! Looking forward to life after professional cricket with her and my two daughters Simone and Maria. I love you guys so much. My mum and dad Anne and Jimmy for being tough but fair while I was growing up. You have always been there for me whatever my situation. The mother-in-law Pat who I hope enjoys life in the west wing; put the kettle on chuck!

If you are not living life on the edge you are taking up to much room!

CHAPTER 1 ‘HE’S BIG AND HE’S BARMY’

CHAPTER 3 THE VIEW FROM MY BEDROOM WINDOW

CHAPTER 4 STOP ME IF YOU’RE FEELING FRUITY

CHAPTER 6 MY PAL, THE WANNABE PORN STAR

CHAPTER 7 SOMEWHERE NEAR THE DARTFORD TUNNEL

CHAPTER 8 LOSTOCK TO CHELMSFORD – THE LONGEST JOURNEY

CHAPTER 9 ARE YOU WATCHING, LANCASHIRE?

CHAPTER 11 WELL DONE, YOU’RE DROPPED

CHAPTER 12 THERE’S SHIT ON THE END OF YOUR BAT

CHAPTER 13 WE’RE THINKING OF SENDING YOU HOME

CHAPTER 14 I WANT TO BE A MOUNTAIN PERSON

CHAPTER 15 COCKSCOMB INJECTIONS

CHAPTER 17 YOU SHOULD INVEST IN DOT.COM

CHAPTER 18 LEAVE ENOUGH GAP TO CREATE A SPARK

CHAPTER 19 YOU’RE THE MAN TO TAKE SACHIN

CHAPTER 20 A LONG STRETCH IN SYDNEY

CHAPTER 21 AT TIMES IT’S LIKE BEING A SINGLE MUM

CHAPTER 22 THE GAME THAT NEVER WAS

CHAPTER 24 MIND GAMES TO WIN GAMES

CHAPTER 25 I’LL BE FRANC, IT’S FRIGHTENING

T

here was a lump in my throat even before I opened the door to make the familiar walk down the steps of Chelmsford pavilion. It was a packed house for a Twenty20 match under floodlights and, as usual, I was wearing the Essex shirt with the red, blue and yellow badge. But I wasn't playing. I would never play again. I knew it and so did the fans. As I reached the pitch they got to their feet and started to sing:

âHis name is Ronnie Irani

âHe's big and he's barmy

âHe bats number five for Essex

âESSEX!

âAll the kids in the street shout

âHey big lad, what's your name?

âHis name is Ronnie Iraniâ¦'

I blinked away the tears, took a firm hold of Simone and Maria's hands and started the most memorable walk of my life.Â

A million thoughts tumbled through my head as I slowly circled the ground with my young daughters, also in their Essex shirts with their names on the back. I could only wave and soak up the emotion of the night. There was no way of telling the fans how much they meant to me. They had adopted a big, raggy-arsed kid from Bolton as one of their own after his dream of playing for Lancashire turned sour. I'd got to know some of them well â Malcolm Singer and his mates, Ian, Anthony and Peter; Tony and Pam and their three daughters; and the late âDel Boy' whose spirit was always with me whenever I walked down those steps and who I hope is âforever blowing bubbles'. Hundreds of others had become familiar faces over the years.

There had been better cricketers at the club, yet somehow the Essex fans picked me out for special attention. I like to think it was because I put all I had into every single ball, whether bowling, batting or chasing around the boundary, and also because, while I played the game hard and to win, I never lost sight of the fact that it was meant to be fun for me and entertaining for them. Some players avoid the fans if they can, but I thoroughly enjoyed the craic and exchanging banter with them. And I believe both the Essex fans and England's âBarmy Army' found it possible to identify with me. They couldn't imagine themselves being Brian Lara or Graeme Hick or Wasim Akram, but they could look at me and think that, if things had been a bit different, they might have been that big bugger whose enthusiasm, hard work and desire to succeed had made the most of his natural talent.

The people of Essex backed me from the day I stepped off the train in Chelmsford, with everything I owned packed into four bags and with only nine first-class matches to show for my five years at Lancashire. Even when England selectors and

officials decided I wasn't good enough or was too much of âa character' to be bothered with, the people of Essex were still on my side. Above all, they had enjoyed the great times for club and country that had made the last 19 years so unforgettable.

I looked up at the box I'd hired for the night. I'd wanted to share the moment with as many of the most important people in my life as I could, including my wife Lorraine, who I'd been with since she was 16, Mum and Dad who had instilled in me their work ethic and love of cricket and who had followed every step of my career, my secretary Linda Bennett, business partners Nick Bones and Aimee and Damian Donzis, Charles Lord from Stuart Surridge who had sponsored me, Rowland Luff the best man at my wedding, and my mentor John Bird. There were many more who I wished could have been there, people who had given me a leg up when I needed it most.

I went over and gave George Clarke a hug. George was the Essex dressing-room attendant and had not only been the first person to welcome me to Chelmsford all those years before but had also been a brave enough umpire to give England legend Graham Gooch out lbw when I bowled to him in my first Essex practice match. That had been an early feather in my cap and helped establish me at my new home. I spotted Graham Saville on the committee-room balcony and waved to him. I trusted him so much that I'd quit Lancashire just on his word that Essex would sign me and, together with Goochie and Keith Fletcher, Sav had guided me through my career from rookie to county captain.

Ironically, I had been at the peak of my form when Richard Steadman, the top knee specialist in the world, told me, âI'm sorry, Ronnie. It's time to call it a day.' It hurt like hell but I knew that, if he said nothing more could be done to patch up

a knee that had troubled me since I was 17 years old, then that was it. I'd been on a rollercoaster of emotions since breaking the news, first to Lorraine and then to the management and my team-mates at Essex. I was easily moved to tears, especially when I read the tribute Graham Gooch paid me in the press: âHis attitude and work ethic have always been spot-on since he joined us 13 years ago. He has never lost his appetite and self-belief and, in his book, there was never such a thing as a lost cause. That was something that lifted everyone around him. At both one-day level as well as in the championship he led by example and produced many match-winning performances that confirmed his status as a superb player.'

It just doesn't get any better than to have one of the greatest players, top leaders and an outstanding man say things like that about you.

It had been a fabulous career â I'd scored lots of runs, taken my share of wickets, picked up trophies, set a record for my country, made some lasting friends, had some great laughs and travelled the world. But I have to say that the greatest single moment was feeling the love from the fans at Chelmsford that night as I walked round the ground with my two âEssex girls'.

As I completed my lap of honour, I saw a familiar face in the crowd. âKush' Dave and his son had been among the first supporters to get behind me. It was he who had started my special song. I went over to him, gave him my last Essex shirt and said, âThanks, pal. It's been a ball.'

I

t only took a couple of days for the harsh reality to become all too clear: I was 36 years old and out of work. At an age when most men are settled into a career and in many cases looking to move into a senior position, I was starting afresh, as though I’d just left school. When I looked at my CV, it was obvious that, as impressive as it might be to wield a lump of willow effectively from the age of six, or make a small, hard ball swing out or in at will, neither talent was much use for anything other than being a professional cricketer. There was an additional snag – in honing those skills, I had somewhat neglected my formal education. There was no degree to impress a would-be employer, indeed not so much as an A level.

I had some ideas I wanted to pursue. I already had my own insole company with partners in Germany and the USA and I had high hopes for that. But it was very much at the development stage and was costing me money rather than bringing it in. I needed something that would make the most

of my other talents and, when I analysed what those were, it came down to a willingness to work hard, boundless enthusiasm, a sense of humour and an ability to talk – some would say an inability to shut up.

Thanks to my natural gift of the gab, I was already commanding quite good money on the after-dinner-speaking circuit, and I would now have time to do more of that. And as Essex captain, I’d done a fair amount of broadcasting, which came quite easily to me, so at the back of my mind I thought I could probably follow some of my fellow

ex-professionals

into the media.

I’d been standing on my hind legs and speaking for about as long as I could remember. In my early days as a teenager at Lancashire, I would be asked to go along to a local cricket club or school and present prizes, sometimes to kids not much younger than I was. And usually someone would ask, ‘Would you mind saying a few words?’ I did mind, a lot. It was embarrassing. I’d mutter something about congratulations on last season and good luck for next season then try to get off as quickly as possible. I could chat forever in the dressing room, much to the annoyance of some of my senior colleagues who felt I should remember my place and shut up, but this was different. This was performing solo and I only felt comfortable doing that out in the middle of a cricket pitch. I felt like a plonker every time I had to speak and was tempted to turn down these invitations but then I remembered how good I’d felt when England footballer Francis Lee came to my cricket club at Heaton, and the excitement around the place when Olympic sprinter Allan Wells visited our school and showed us his gold medal. I reasoned that, if these people could put themselves out for a nobody from Bolton like me, the least

I could do was to get over my nervousness and talk to a few kids from time to time.

Over the years, it became second nature to speak in front of people for a couple of minutes, but that was a lot different from my first proper ‘gig’ as an after-dinner speaker. By the time Woodford Wells Cricket Club invited me to speak at their presentation night, I was an England player and beginning to be a favourite among the Essex supporters.

‘Just come along and hand out the prizes and maybe talk for about 20 minutes,’ the secretary suggested, smiling encouragingly.

I didn’t like to tell him I’d never done anything like that before. I swallowed hard, agreed and then thought, What the hell do I talk about?

The shadow of that speech hung over me for several days. To say I was panicking would be an exaggeration, but not much of one. I started to scribble down all the questions fans usually asked me. Who’s the fastest bowler you’ve batted against? What’s it like facing a bouncer that flies at your head? Who was your favourite player when you were growing up? Who was the better captain – Mike Atherton or Graham Gooch? Who is the funniest guy in the Essex dressing room? What does it feel like to drop a catch? I reckoned, if I strung the answers to those into a series of stories, I would probably be OK, although I wasn’t sure if cricket was going to be high on the agenda when my formal invitation arrived and I saw that the other speaker was a guy called Sid Dennis, a

scrap-metal

merchant from Skegness. Wonder why they want to hear about the scrap-metal business? I thought.

As it happened, I turned up at the venue at the same time as Sid and the fact that he was driving an E-class Mercedes suggested there must be plenty of money in being a

‘metal-materials

recycler’, as he described his job on the card he handed me. Sid looked like a dodgy nightclub bouncer. He weighed 20-odd stones, his head was as smooth as a polished egg, and, if owners grow to resemble their dogs, Sid definitely had a bulldog or two back in Skegness.

I sat next to him on the top table, looking out at a sea of around 300 faces. I was shitting myself. My nerves weren’t improved when one of the club members came up to ask for an autograph and said, ‘I’m really looking forward to your speech.’ Suddenly I realised that

I

was the entertainment and these people’s enjoyment of the evening was at least in part down to me. I confessed to Sid that I was an after-dinner virgin and feeling as nervous as hell.

He smiled reassuringly. ‘Don’t worry, lad, you’re not dead yet. You’ll be reet here. Every speaker is only as good as the crowd and this lot are OK. Just remember, they want to know what it’s like to be a professional cricketer. They would love to be able to do what you do, to meet the people you meet, and to be in that dressing room, padded up and waiting to go out to bat in front of thousands of people. Talk about what you know and they’ll love it.’

Just before I stood up, Sid slipped me a piece of paper and said, ‘Kick off with that.’

I read what he’d written, memorised it and got to my feet, gripping my notes firmly and hoping people couldn’t see how much they were shaking. ‘Good evening,’ I said, my mouth as dry as an Indian wicket. ‘For those of you who don’t know me, my name is Ronnie Irani and I play cricket for Essex. I should tell you that I wasn’t born in Essex but, one thing’s for sure, I could fucking die here tonight.’

The audience roared with laughter. The ice was broken and I started to feel a bit better. Thanks, Sid.

I went through my stories and the audience seemed to be interested and even laughed in the right places. By the time I reached my final story, I was enjoying myself.

I said, ‘You are probably wondering what it’s like in the dressing room before a big match. It varies a lot according to the captain. Graham Gooch is quietly encouraging, while others try to gee you up with a rousing speech, like Mike Atherton before the Test at Edgbaston. Ath was obviously feeling Churchillian. He stood before us and proclaimed, “What we have to ask ourselves is, are we men or are we boys? We are about to represent our country so it’s time to decide if we are men or boys. The fans expect us to deliver a victory. Are we men or are we boys? Millions will be watching us around the world on TV. Are we men or are we boys?” At that moment the umpire knocked on the door and Mike yelled, “Come on, let’s go, boys!”’

When I thought back, I wasn’t sure it was Mike Atherton who’d said it – his final gee-up was usually: ‘Let’s fucking get out there’ – but it was a good story and the audience laughed loudly then applauded as I sat down. One or two even stood up and clapped.

Sid squeezed my knee and said, ‘Well done, lad. You did great.’ Then he eased his way to his feet, looked out at the crowd and said, ‘I’d like to thank Ronnie for his speech. I thought it was brilliant. Mind you, gentlemen, I’ve played a bit of cricket in my time and I don’t fucking bang on about it like he does!’ That got the biggest laugh of the night.

As we made our way to the cars afterwards, I thanked Sid and said, ‘That’s a great motor. It’s even better than Graham Gooch’s and he was captain of England. It must be worth at least fifty grand.’

‘Fifty-five, lad, and paid for by doing stuff like this. You

did well tonight. You can do this. You need to sharpen up a bit but that will come with experience. I’ll see you around.’

Over the years, I’ve worked with a lot of fine comedians, people like Mike Farrell, Adger Brown, Jed Stone and Ian Richards, who can be guaranteed to put on a good show at any dinner. But Sid Dennis remains my favourite, partly because he’s hilarious but mainly because of his generosity that night.

As I’ll relate later, not all my gigs have gone as well as that one, but I managed to build up a decent reputation as a speaker who was not only entertaining but could also be relied on to turn up and not drop organisers in the shit at the last minute. However, as lucrative as the circuit can be, it wasn’t going to be enough to pay all the bills and provide the funds to get the company up and running. I needed something else.

As well as cricket interviews on Sky, the BBC and Channel 4, I’d appeared on a number of TV shows as varied as

A

Question of Sport

, kids’ Saturday-morning programmes and the groundbreaking

TFI Friday

with Chris Evans and Will Macdonald, which was the only show where it seemed compulsory to down several pints before going on air. I’ve had a few nights on the lash with Chris and Will, including one where Chris tried to match Alan Brazil drink for drink and only realised he’d failed when he fell down the stairs while Alan strolled down nonchalantly. Chris is a terrific guy and for me one of the best broadcasters this country has produced in recent years. His radio work inspired me to get into it. Will is a brilliant producer and a keen cricket enthusiast like Chris, and is someone you can always rely on. A good mate.

Radio is my favourite medium. It is much more relaxed

and spontaneous, more intimate. There’s not the clutter of cameras and lights that inevitably make TV more formal. There’s nothing between you and the listener but the microphone which allows you to chat to them in their homes, in their cars or on the beach. I’d always made myself available for interviews as a player and was happy for 5 live or talkSPORT to ring me up for a quick word and never dreamed of asking for payment. My first solo broadcast came when Kevin and Vicky Stewart, the owners of the Chelmsford-based station Dream FM, invited me to present the drive-time show every Friday night during the winter on the recommendation of my car sponsor Mike Lumsden of Mercedes Benz Direct. They really took a punt on my popularity as Essex captain and gave me loads of good advice, not least just to be myself and talk to the audience as though I was talking to a couple of people in a bar. I played some of my favourite music, chatted about sport and conducted my first interviews, many of them with mates like Jamie Redknapp, Jamie Theakston and Graham Gooch. Phil Tufnell even came into the studio for a chat and a laugh. It all seemed to go well and planted the seed that it might be something I could try when cricket was over.

Although cricket was my chosen profession, I’d had a passion for all sports since I was a kid. I grew up in a house in Bolton where the talk rarely moved off Manchester United in the winter and local cricket in the summer, with plenty to discuss about athletics, tennis, rugby league, horse racing or anything else that happened to be on the television in between. I even had a couple of snooker lessons with local legend Tony Knowles. So, while it may sound corny for me to say this in view of my present employment, talkSPORT really was my favourite radio station. I used to have it on in

the car as I drove to and from training or matches and loved its mix of informed comment, banter and irreverence. They realised I was always happy to go into their studios and I was interviewed on the afternoon show by Paul Hawksbee and Andy Jacobs, and on Rhodri Williams’s Sunday show. After one visit, Andy Townsend said, ‘You want to keep in here. You never know – when you’ve finished playing, it might be something you could do.’

I must have done something right because, when Paul Hawksbee went on holiday one year, I was invited to sit in with Andy Jacobs. I said yes straight away and hastily rearranged my other commitments to leave my afternoons free. After a couple of training days with Matt Smith and a chat with Andy, I found myself on air as a co-host on one of the most popular shows in speech radio. Looking back, I know I wasn’t that good but it was great experience and Andy was terrific, jumping in to rescue me whenever I started to struggle. My admiration for professional broadcasters went up enormously. It had never occurred to me that something as apparently simple as reading out an email or just holding a conversation with someone across the desk could be quite tricky in practice. You had to make it sound like you were chatting normally but without all the cutting across each other and half-finished sentences that you get among friends in a pub. Suddenly I realised that making it sound natural was harder than I’d thought.

For all the awkwardness I felt at times, I still enjoyed doing the show and the management clearly thought I had some potential because they asked if I would continue to do regular sessions. I was tempted but had to turn them down because it would have interfered with my cricket. But I kept in touch and, by great good fortune, when I was forced to hang up my

cap, a vacancy came up to work as a pundit on their cricket coverage. Shortly after that, they offered me a regular spot alongside Alan Brazil on the breakfast show. It meant getting up at 3.30am, six days a week but I didn’t think twice.

Working with Alan turned out to be a fabulous experience. He knows what it’s like to make the transition from sport to radio and he helped me avoid many of the traps that lurk around the corner in live broadcasting. I was his first ‘rookie’ co-host but he was patient, generous and incredibly supportive.

Al may come across as a feisty Scot who just talks off the top of his head but everything he says is based on a profound knowledge and love of all sport and his exceptional ability as a communicator. There’s hardly any subject that he isn’t well informed about. I smile every time he comes out with ‘As you realise, I know nothing about cricket’ because I know he’s just about to utter a gem that cuts right to the heart of whatever we are discussing.