No Buddy Left Behind: Bringing U.S. Troops' Dogs and Cats Safely Home From the Combat Zone (5 page)

Authors: Terri Crisp; C. J. Hurn

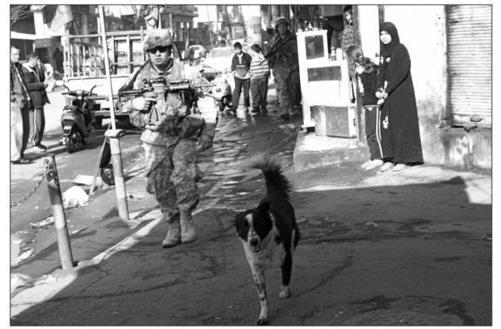

Charlie on patrol in Baghdad Eddie Watson

Charlie on patrol in Baghdad Eddie Watson

he afternoon staff meeting in late October 2007 had reached the point where I began to doodle in the margins of that month's agenda, and I couldn't stop thinking about the unfinished pile of work on my desk.

he afternoon staff meeting in late October 2007 had reached the point where I began to doodle in the margins of that month's agenda, and I couldn't stop thinking about the unfinished pile of work on my desk.

"Before we finish," said Nancy, one of SPCA International's web team members, "I have one more item to bring up."

A small groan escaped. Was that me?

"This e-mail came through our website last week." Nancy passed a copy to each of us as she spoke. "I haven't been able to get it out of my mind. The original was written several weeks ago by a soldier stationed in Iraq, and since then it has been forwarded from one organization to another."

At the mention of Iraq, I stopped doodling.

The e-mail had been written by a SGT Eddie Watson and was addressed to "Whoever Can Help Charlie."

"This is really sad," said Stephanie, the Director of Communications. She echoed what I was feeling as I read the following message:

Our unit rescued Charlie from the streets of Baghdad, and since then he has become a mascot and loyal friend. But it is against military rules to befriend animals or use military vehicles for animal transport. In March of 2008, we will redeploy. I'd like to find a way to bring Charlie home to America, but the biggest stumbling block is finding transport. At around six months of age, he's still just a puppy. He deserves a chance. Please, can you help us get Charlie home?

The room filled with silence as each person read SGT Watson's history of how the soldiers found Charlie and what the dog meant to the men in his platoon. Scanning the long list of forwarded addresses, I realized that we at SPCA International might be Charlie's last hope.

"How can the military expect soldiers to leave their beloved friend behind? Don't soldiers give enough to this country?" Matt, another member of the web team asked. "I mean, how much space could a dog take up?"

Having some prior knowledge about the military policy on animals, I explained that General Order 1A had been issued by U.S. Military Central Command in 2000 to clearly state prohibited activities and conduct for U.S. military troops and contractors in war zones, particularly in countries like Iraq and Afghanistan where cultural and religious differences needed to be respected. Any conduct or activity that threatened the good order and discipline of troops came under the umbrella of General Order 1A, including befriending, feeding, or transporting stray animals. Any person who broke the rule risked punishment under criminal statutes.

"I can understand that the military has to maintain standards," said JD Winston, our new executive director, "but it sure seems harsh to expect these guys to ignore a starving puppy that follows them and has no chance of survival without some help. I know I would find that extremely difficult to deal with."

"Welcome to the dilemma faced by the guys at the top level of military," I said. "They know it's a problem, and most of them feel sympathetic to the soldiers who get caught in this situation. A lot of them agree that having a loyal four-footed friend in a war zone is a great morale-booster and comfort for the men. But their main concern is not about saving animals. They have to focus on getting in, getting the job done, and getting the soldiers back home-alive."

No longer anxious to return to my desk, I stood up to replenish my coffee and looked around the room. I hadn't seen us this collectively captivated in a long time.

"I can understand how a dog would make a big difference to the soldiers," Stephanie said. "Can you imagine the horrific scenes these guys have to face every day?"

Nancy looked around the table as we all shook our heads in sad agreement. "This isn't only about saving a dog," she said. "It's about supporting our troops.

My eyes wandered to the windows, and I stared at the smoggy haze hanging over southern California. This wasn't the first time I had heard about soldiers bonding with a dog while fighting a war far from home.

JD spoke up. "Let's give it a shot and see what we might be able to do." Then he turned toward me and continued, "Terri, you've had lots of experience with disaster rescues. My guess is that saving Charlie will present the same kinds of coordination issues you've dealt with before. It makes sense for you to look into this. Besides," JD smiled, "you have been saying you wanted to take on a new challenge. How about taking on this one?"

A quick succession of practical questions flooded my brain. How would Charlie adjust to living in the States? What if the changes were just too much for him, and he didn't fit in? We certainly couldn't send him back.

Everyone at the table waited for my answer.

"Last year," I said, "a woman I know helped her brother to get a dog that he had befriended out of Afghanistan and into the United States. It took months of hard work, but thanks to volunteers from across the globe, they did it."

No one said it, but I'm sure we all thought it: If a dog from one country at war could be saved, why not another?

"So, does that mean you think you can do it?" Stephanie's question drew all eyes to me again.

Talk about pressure. Taking a second to consider, I responded with an unequivocal "Yes!"

"That's great," said JD, closing his notebook. "See what you can find out and report back to me. Hopefully, we'll be able to help SGT Watson and Charlie."

Returning to my desk, I pushed aside my other work. I couldn't wait to start the preliminary research on my newest challenge, but where should I begin? Already I felt stuck.

"Come on, Terri," I said to myself. "You've taken on the seemingly impossible before in disaster situations. Don't freeze up. Remember what you've learned."

I hoped no one overheard my private pep talk.

"Push aside negative thoughts. Focus on the goal, keep walking forward, and trust that the right things will happen."

Panic moment over, my brain slipped into gear and identified transport as the first priority. I began a computer search using Expedia.com. I typed in "Baghdad, Iraq" for the flight departure city and randomly picked "Washington, D.C." for the arrival city.

"Destination Currently Unavailable," Expedia reported. I had to admit that I wasn't surprised. No one in their right mind would be traveling between Iraq and the United States unless Uncle Sam was their travel agent.

Using less familiar avenues for booking air travel, I came no closer to finding flights in or out of Iraq. If we couldn't get a flight out of Iraq, maybe we'd have to drive Charlie to a neighboring country and fly from there; but which one? I couldn't remember the countries that bordered Iraq, so I Googled a map of the Middle East. Iran was out of the question. Kuwait might work. After all, American troops did come to the rescue when Saddam Hussein tried to take over that country. Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Syria provided other possibilities. Good. Now I had some options to explore and no longer felt stuck.

Seeking sources of land travel, I discovered that no trains in Iraq cross the border, and the few Google images of public buses showed what looked like death traps on wheels. Major car rental companies weren't available either. Turning to websites that specialize in transporting animals all over the world, I learned that none of them does business in Iraq. This was turning out to be a travel agent's worst nightmare.

In twenty-five years, responding to seventy-one major disasters, I had met challenging logistical situations that drew upon all my resourcefulness. But none had been like this. It was time to start thinking way outside the box, but by the day's end, even years of experience hadn't been much use in solving the problem.

That night, as I lay in bed with Eddie's dilemma swirling around in my brain, I realized that his plea had taken my routine day and turned it into one that presented a familiar kind of excitement, one that I thrive on during disasters. It felt good, once again, to be faced with seemingly insurmountable obstacles. Yet, just before I fell asleep, I thought, "I have to e-mail Eddie tomorrow, but what on Earth am I going to tell him?"

The next morning I calculated the time difference between California and Iraq and determined that it was 5:30 p.m. in Baghdad. I wondered when Eddie would check his e-mails and hoped he might be preoccupied with hunting down insurgents. The longer it took for the two of us to connect, the more time I would have to find at least one tidbit of good news. The frustration I felt after only one day of searching made what Eddie had been grappling with for the last few months uncomfortably clear. I repeated the mantra, "You'll find a way. You can do it."

The morning produced no more answers, despite brainstorming with my co-workers Matt and Jennifer, both members of the web team.

"I've got it," I laughed. "I'll call the Commander-in-Chief and ask him to intervene. You know, to put Charlie on Air Force One. If he refuses, I'll call Mrs. Bush. Surely she'd let me borrow their plane for a few days if it's helping one of our soldiers."

"Either that, or do a PETA-style stunt to attract awareness," offered Jennifer.

"You mean, strip down to my birthday suit and chain myself to the White House fence?"

Laughter helped to ease the tension, but by the time Matt finished his second cup of herbal tea, we hadn't come up with any workable solutions.

"Don't give up, Terri," Matt said as he walked back to his cubicle. "You'll figure it out."

Before doing anything else, I had to e-mail Eddie. It wasn't fair to leave him hanging. He'd done enough of that already. Having read articles about servicemen and women returning from Iraq with emotional scars, I didn't want to contribute to Eddie's burdens by dumping my frustration on him. This had to be a message of hope. I also needed to ask him some key questions before I could go much further in my search.

Taking care of how I worded my reply, I wrote that we at SPCA International were moved by Eddie's request. After hearing his story, we all agreed we wanted to help him save Charlie. I assured Eddie that he deserved all the assistance he could get, considering how hard he had been trying to keep his four-legged friend alive. I also explained that I would be his SPCA International contact, but I was a novice at finding transport out of war zones, so it might take me a while to unravel the puzzle.