No Joke (5 page)

Authors: Ruth R. Wisse

The young man was most disagreeably surprised when the proposed bride was introduced to him, and drew aside the

shadkhen

âthe marriage brokerâto whisper his objections: “Why have you brought me here?” he asked reproachfully. “She's ugly and old, she squints, and has bad teeth ⦔ “You needn't lower your voice,” interrupted the broker, “she's deaf as well.”

Two Jews meet in a railway carriage at a station in Galicia. “Where are you going?” asks one. “To Cracow,” replied the other. “What a liar you are!” objects the first. “If you say you're going to Cracow, you want me to believe you're going to Lemberg. But I know that in fact you're going to Cracow. So why are you lying to me?”

A schnorrer, who was allowed as a guest into the same house every Sabbath, appeared one day in the company of an unknown young man who was about to sit down at the table. “Who is this?” asked the householder. “He's my new son-in-law,” the schnorrer replied. “I've promised him his board for the first year.”

3

In the first joke, expecting the shadkhen to parry the young man's objections, we are surprised that he reinforces them instead. In the second, convolution, which normally serves to obscure the truth, ends up confirming it. In the third, the beggar assumes the host's prerogative, manifesting largesse at the expense of his benefactor. Reversal, displacement, and turning the tables are the wellsprings of a tradition that mocks the contradictions of Jewish experienceâthe gap between accommodation to foreign powers and promise of divine election. Although many religions acknowledge a tension between the tenets and confutations of their faith, few have had to balance such high national hopes against such a poor political record. Jewish humor at its best interprets the incongruities of the Jewish condition.

But I am doing what Freud does not. Though he draws heavily on the humor of his native Jewish culture, he extrapolates from it only such findings as are presumably universal. He is interested in the relation of joking to other psychological phenomena, not in relation to Jews. “[We] do not insist upon a patent of nobility from our examples,” he writes. “We make no inquiries about their origin but only about their efficiencyâwhether they are capable of making us laugh and whether they

deserve our theoretical interest. And both these two requirements are best fulfilled precisely by Jewish jokes.”

4

One can't help musing on the analyst's reluctance to comment on the Jewishness of the Jewish material he discusses. Take a phrase like “patent of nobility”âtransposed from the Yiddish

yikhes-briv

, a hybrid Hebrew-Yiddish term for pedigree. The irony implicit in Freud's use of the term, which follows a joke about Jews' aversion to bathing, derives from the distinction between Jewish and Christian-European concepts of nobility, with each side looking down on the standards of the other. Freud's obvious pride in the claim of Jews to primogeniture as well as cultural and ethical advantages over their Christian overlords belies the scientist's claim to be transcending parochialism.

Only once in this book does Freud indulge in some speculation about the specifically Jewish affinity for humor. He does so during a discussion of tendentious jokes, “when the intended rebellious criticism is directed against the subject himself, or, to put it more cautiously, against someone in whom the subject has a shareâa collective person, that is (the subject's own nation, for instance).” In other words, Freud makes a distinction between jokes directed by Jews at Jews and jokes directed at Jews by foreignersânot because the former are any kinder, but instead because Jews know the connection between their own faults and virtues. “Incidentally,” he concludes this part of the exploration with a sentiment already cited in the introduction, “I do not know whether there are many other instances of a people making fun to such a degree of its own character.”

5

The offhand quality of this observation

has not prevented it from becoming the most quoted sentence in Freud's book, perhaps because others have realized better than the author how much it says about the Jewish condition.

Herzl and Freud, otherwise so alike in their German Jewish ambience and restless intelligence, reached opposite conclusions about Jewish humor. Both recognized its connection to anti-Jewish hostility, but Freud admired what Herzlâlike Schnitzler in

Der Weg ins Freie

âfeared. Freud put up with anti-Semitism in much the same way that he accepted civilization

with

its discontents (to paraphrase the title of one of his most famous works).

6

He therefore welcomed joking as a compensatory pleasureâthe expressive venting of people who lived under the double weight of their own disciplining heritage and the collective responsibility to behave well among the nations. Herzl, in contrast, wanted to alleviate anti-Semitism for the betterment of Europe as well as the Jews.

Which of the two thinkers do we consider the greater “realist”? Which the greater optimist? Which the greater healer? At issue here is the degree to which the two men's approval of Jewish wit was proportional to their respective plans, if any, for Jewish rescue.

Heine

Heine

The fountainhead and genius of German Jewish humor was neither Herzl nor Freud but rather Heine, who was also the most controversial figure in modern German literature.

7

Coming of age at a moment when Jews were being admitted to

German society, Heine knew he had something fresh to introduce into the high culture of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich von Schillerânamely, a literature less focused than theirs on achieving comprehensive truth and classical perfection, and thus truer to the volatile realities of the day. Had his precursors not set a high bar for German literature, he might not have held himself to a standard of honesty and self-exposure that was bold to the point of recklessness. But whatever the motivation, no Jewish writer ever took more aggressive risks.

Born in Düsseldorf, then under French rule, in 1797, Heine published his first book of poems in 1821. Though he studied law and philosophy, he was a natural poet, pushing the form to the limits of lyrical, political, and critical expression. His writing drew on warring elements in his nature: romantic longing versus analytic skepticism, socialist sympathies tempered by monarchist preferences, and a love of the German language and homeland that endured a quarter century's residence in France. In his lyrics, Heine proved that he could “do” perfection; over seventy-five composers, including Franz Peter Schubert, Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, Franz Liszt, and Richard Wagner, set his poems to music. Sharing a widespread contemporary attraction to folk poetry, Heine achieved some of its effects of “artlessness” in his art. But he was just as keen to register imperfectionsâin politics, human nature, and himself. Heine's trustiest biographer, Jeffrey L. Sammons, advises extreme caution in describing both who Heine was and who Heine thought he was, and the avalanche of arguments over his legacy renders foolish any attempt to provide a definitive characterization of the man and his career.

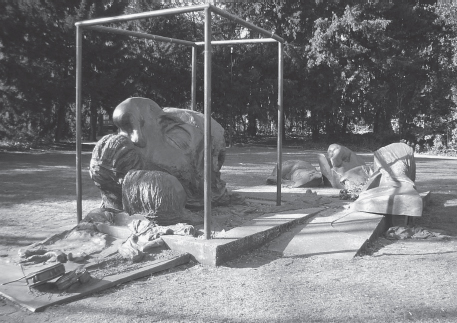

Controversy over the memorialization of Heine in Germany has kept pace with the controversy over his work. This monument in Düsseldorf's Swan Market by the sculptor Bert Gerresheim situates an enlarged replica of the author's death mask in a landscape of ruin. The prominence of the nose in this magnified form disturbed some viewers as a reminder of the anti-Semitic trope of the Jewish noseâa trope exploited for humor by Heine himself.

Heine's conversion to Christianity, for exampleâan act that was fairly common among his Jewish contemporariesâacquired notoriety only because he cast himself as at once a renegade Jew and phony Christian. He called his conversion an

Entréebillet zur europäischen Kultur

âa jibe that had many teeth. By using the French term for “ticket of admission,” he implied that the German language had to pay its own ticket of

admission into European culture, just as the Jew paid through baptism for his. In addition, the commercial terminology mocks both conversion as a religious experience and the person who submits to it, not to mention others as well. Christians are ridiculed for accepting inauthentic converts, Jews for trading their culture for one that despises theirs, and enlightened Europeans for exposing the bias at the heart of their liberal affectations by requiring the credential of Christian baptism that they otherwise pretended to spurn. In a single breath, Heine thus damns all parties to the dishonest bargain and himself most of all, since he knew that the teaching post he hoped to gain by his conversion had not come through. Like Samson among the Philistines, he pulls down the pillars of the civilization that had seduced him, acceptingâor rather seekingâhis own punishment along with that of his seducers.

When I studied eighteenth-and nineteenth-century European literature in college, Heine's lyric “Ein Fichtenbaum steht einsam” was presented as the epitome of Romantic longing. It depicts a pine tree standing lonely on a northern height, slumbering under its cover of snow and ice, and dreaming of a palm tree, in the East, that mourns lonely and silent on a blazing cliff.

Ein Fichtenbaum steht einsam

Im Norden auf kahler Höh.

Ihn schläfert; mit weisser Decke

Umhüllen ihn Eis und Schnee.

Er träumt von einer Palme,

Die, fern im Morgenland,

Einsam und schweigend trauert

Auf brennender Felsenwand.

8

[There stands a lonely pine-tree

In the north, on a barren height;

He sleeps while the ice and snow flakes

Swathe him in folds of white.

He dreameth of a palm-tree

Far in the sunrise-land,

Lonely and silent longing

On her burning bank of sand.]

9

Male pine and female palm, each solitary, majestic, and destined to yearn for what can never be joined, are coupled in the harmonious medium of a liedâGerman for poem and songâthat forges their conciliation across the gap between the two stanzas. The accord of the words supplants the rupture of feeling.

This is the kind of poetry at which Heine excelled, but it was not the only kind. Another way of expressing the same

Zerrissenheit

âthe condition of being torn apartâwas through wit. This, too, yokes opposites, although instead of harmonizing the disjunction, wit accentuates it by means of verbal surprise. In fact, Heine was superb at puncturing the very ideals of love and beauty that he elsewhere upheld. Although by no means the only practitioner of the aggressive wit that came to be known as

Judenwitz

(a form also practiced by non-Jews), he became its master.

If I were teaching European Romanticism today, I might tweak the syllabus to include, alongside “Ein Fichtenbaum,”

one of Heine's comic takes on the Romantic poet (that is, himself) who wrote it. “The Baths of Lucca,” one of his four so-called travel pictures, has the added advantage of being a send-up of Jews. The parody begins with the genre. Modeling himself on then-popular accounts of which the best known was Goethe's

Travels in Italy

, Heine confesses that “there's nothing more boring on this earth than to have to read the description of an Italian journeyâexcept maybe to have to write oneâand the writer can only make it halfway bearable by speaking as little as possible of Italy itself.”

10

Accordingly, the Tuscan resort town of Lucca serves Heine merely as the setting for an encounter among displaced German Jews who have come to take the baths.

The plot of this travelogue is minimal. The implied author, identified as Heine, doctor of laws, drops in on Lady Matilda, whom he had previously known in London. The narrator recognizes a second visitor as the converted Jewish Hamburg banker Christian Gumpel, now the Marquis Christoforo di Gumpelino, who pronounces himself madly in love with Matilda's countrywoman, Lady Julie Maxfield. To while away the time, the two prospective suitors set out to visit Gumpelino's local Italian lady friends. Huffing and puffing through the picturesque hills of Lucca, they encounter Gumpel's valet, also recognizable to the author as Old Hirsch, his former Hamburg lottery agent. While the author and Gumpelino pay an extended visit to the Italian courtesans, the servant is dispatched to arrange an evening rendezvous for his master with Maxfield. The erotic adventure subsequently falls through, and the work concludes with an improbable discussion of

poetry in which the “author” makes merciless fun of August von Platen (1796â1835), a fellow poet in real life. This part of the work damaged Heine's reputation harder than it did von Platen's.