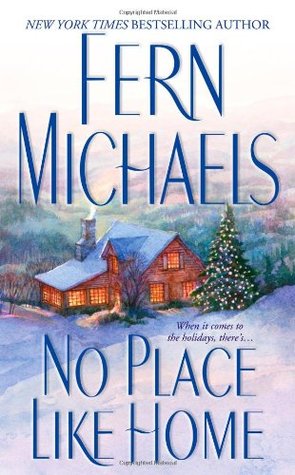

No Place Like Home (Holiday Classics)

Read No Place Like Home (Holiday Classics) Online

Authors: Fern Michaels

New York Times

bestselling author

Fern Michaels

“Michaels delivers another corker with her latest romantic suspense story…. Highly recommended where stylish suspense circulates.”

—

Library Journal

“A thoroughly engaging read.”

—Amazon.com

“A fun romance from a popular master of the genre.”

—

Booklist

“Equal parts glitz and true grit.”

—

Publishers Weekly

“Enough melodrama to please a J.R. Ewing or Alexis Carrington.”

—

Publishers Weekly

THE DELTA LADIES

WILD HONEY

Published by POCKET BOOKS

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

An

Original

Publication of POCKET BOOKS

A Pocket Star Book published by

A Pocket Star Book published byPOCKET BOOKS, a division of Simon & Schuster Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

Copyright © 2002 by First Draft, Inc.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Pocket Books, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

ISBN-10: 0-7434-7718-9

ISBN-13: 978-0-7434-7718-5

POCKET STAR BOOKS and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc.

Visit us on the World Wide Web

http://www.SimonSays.com

For all those near and dear to my heart who truly know there is no place like home.

L

oretta Cisco, founder and CEO of Cisco Candies, opened the screen door leading to the back porch, Freddie, her golden retriever, at her side. The door squeaked and groaned just the way an old screen door is supposed to creak and groan. Just the way her old bones creaked and groaned, she thought. A smile tugged at the corners of her mouth.

It was autumn, her favorite time of the year. Even though she couldn’t see the gold-and-bronze leaves because of the milky white cataracts covering her eyes, she could

smell

the air in the foothills of the Allegheny Mountains. To her, autumn had its own distinctive smell, just as the other seasons did.

She knew where every tree, every bush, every flower, every twig was. After all, she’d lived her entire life here in the rich foothills of the mountains. Oh, she had a fancy apartment in New York, where Cisco Candies had its corporate offices, and yes, she visited it twice a year. But it had never been

home.

Home was this winterized cottage she’d expanded and improved upon. She even had a big, old barn where she kept her car, her grandchildren’s three red jet skis on their trailer, their mountain bikes, snowmobiles, sleds, winter skis, water skis, Sam’s canoe and all his mountain-climbing equipment, and all the gear a set of triplets needed to get through their young lives. She knew where everything was in the barn, too, because when she got lonely, she’d walk out there with Freddie, touch the various things, and her memories would surface. More often than not, she cried.

Loretta walked across the porch, past the four Adirondack chairs with the heavy padding, past the round table with the hurricane lamp in the middle, until she was at the top of the steps. Freddie inched her closer to the railing. She smiled as she carefully descended the four steps to the garden path. Her hands reached out to touch the holly bushes. She had four. Most people didn’t know you needed a male and a female bush to get the lush red berries that were so precious at Christmastime. Her hands worked at the prickly leaves until she felt the different sprays of berries. The berries were probably still green and would not turn red till around November. They felt full and lush this year. She wished she could see them, for she loved holly, especially the variegated kind. For sure they would have fresh holly in the house for the holidays.

She bent down at the end of the holly row to let her fingers touch the velvety petals of the chrysanthemums, which were as big and round as bushel baskets. She hoped they looked vibrant this year. There were four that were a deep purple in color, two lemon yellow, and nine bronze with gold tips. They were almost as old as she was. She wondered how many people knew you had to pinch the suckers off the plants to make them grow round and fat. Just like you had to pinch them off tomato plants. She hadn’t known it either until a neighbor told her.

She continued her walk to the little garden she’d planted when the triplets were born. Freddie nudged her leg again, signaling her that she was slightly off course. Three birch trees. Her son had carved all their initials in the spindly trunks, which had expanded over the years. Her hands could no longer encompass them and the initials were still there. Jonathan had said he wanted their names to withstand time and the elements, Sara, Hannah, and Sam. Then hers, and Jonathan’s, and, of course, Margie’s. She’d always felt a little guilty over those three trees, wondering why she’d never planted one when her son was born. The best answer she could come up with was, it had been a different time, and people had thought differently back then. Her touch was reverent as her fingers traced the carvings. So many years ago.

“Let’s check out the pumpkin patch, Freddie. The temperature is starting to drop, and I can feel the sun starting to fade.” She walked slowly, savoring the warmth of the late-afternoon sun. “Ah, we’re here. Show me where they are, Freddie. Oh, I wish I could see them. I guess I have to get down on my knees and feel around.” She’d planted six pumpkin plants in the early spring, the way she did every year. Her eyes hadn’t been so bad back then. On her knees, her arms stretched out, she counted them. Nineteen pumpkins, each as big as a beach ball. When the triplets were little, they’d carved them all and lined them up along the driveway, the candles in the center glowing brightly in the dark night. The triplets were in college now and didn’t come home for Halloween. She still planted the pumpkins, though; she thought of it as a tradition rather than a habit.

It was Sam who loved to toast the seeds. Sometimes he put sugar on them, sometimes salt. Then, when he was all finished, Sara and Hannah would snatch them away. Sam was so good-natured, he’d just shake his head and make another batch.

Loretta dusted off her hands and knees. The wind picked up, ruffling her snow-white hair. She looked up, knowing she was standing under the old sycamore where they picnicked every year. Her voice cracked slightly when her hand reached down to pat her loyal companion. “I love this place, Freddie. I think I would die if I ever had to leave here. My whole life is here, along with all my memories. I wouldn’t know what to do someplace else.” Freddie barked to show she understood as she guided her mistress back up the garden path to the back porch.

When she reached the top of the steps and walked past the four Adirondack chairs, she stopped to smell the air. Someone over the hill, probably the new neighbor she’d heard about, was burning leaves. She dearly loved the smell. Another memory.

Her kitchen wasn’t modern like the ones she saw in the glossy magazines because she didn’t want a shiny state-of-the-art kitchen. It wasn’t that she didn’t like new things, she did, but this kitchen was hers and she simply liked it the way it was. She’d laughed there, cried there, comforted her son and grandchildren there. It was where they’d congregated after her daughter-in-law’s funeral. It was where they sat holding hands, wondering how they were going to go on without Margie. They did go on because they had no other choice.

Loretta poured herself a cup of coffee and carried it to the old scarred table that could sit eight comfortably.

It was a large, old-fashioned kitchen. Maybe that’s why she loved it so. The stove was old, with six burners and pilot lights that miraculously never went out. The oven was just warm enough to dry the orange peels and cinnamon sticks she replenished from time to time. The scent carried through the old house, even to the second floor. The triplets said they loved coming into the house because they loved the smell. The refrigerator was an old-timer, too, big enough to hold enough food for an army. The triplets, her son, Freddie, and herself were her army. The heavy-duty dishwasher was her only concession to what she called modern wizardry. She only used it when the triplets were home. The cabinets were painted white, with beveled glass insets. The windows, and there were six of them, were diamond-paned and adorned with red-and-white-checkered curtains. They probably needed to be washed by now because she hadn’t touched them since she did her spring cleaning. The floor was old, craggy, and ridged, heart of pine. It was beautiful because she’d cared for it lovingly. She knew every crack, every ridge, every knothole. Rag rugs she’d braided herself were by the sink and stove. When it was time to clean them, she hung them over the banister on the back porch, hosed them off with soapy water, and let them dry in the sun. They were old, too, at least thirty years or more.

She walked around the big, old kitchen, touching the bright ceramic apple that held Freddie’s chews instead of cookies. The triplets had made the apple at summer camp one year. Her hands reached out to touch the raised hearth that was arm level with her rocker. In the winter she planted seedlings and kept the little clay pots in the corner where it was nice and warm and got just the right amount of sun from the nearby window.

There probably wouldn’t be any seedlings this year. There probably wouldn’t be a garden either.

What she loved most about her kitchen was the cavernous fireplace that took up one whole wall of the room. In the winter months, she spent most of her time right there in the kitchen, rocking in her mother’s old rocker, knitting scarves no one ever wore. When her vision had turned bad, she’d stopped knitting and started to listen to books on tape. She had tons of them, thanks to the triplets. One of Freddie’s five beds was next to Loretta’s rocker, along with a pile of her toys. Sometimes they both slept in the kitchen—she in her rocker, Freddie in her bed.

Loretta finished her coffee. It was time to start dinner. First she removed the tray with the orange peels and cinnamon sticks from the oven. She leaned over to listen to the click of the oven switch. It was one click for 325 degrees and two clicks for 350. When she heard the second click, she lowered the oven door and turned to the refrigerator. She withdrew two trays. Meat loaf, mashed potatoes, peas and carrots, and cauliflower. She added two biscuits from a Ziploc bag and placed the trays in the oven.

It was time to wash up for dinner, and time to

listen

to the six o’clock news on the television.

It was after eight o’clock when Loretta put away the last dish, let Freddie out, and then changed into her nightgown and robe, and let Freddie back in. She was going to sit on the rocker and listen to a new book on tape her grandson Sam had sent her.

Another day was coming to a close.

Before Loretta settled herself in the rocker, she reached into the cookie jar for one of Freddie’s rawhide chews. Now they were ready to settle down for the night. No, not quite. She needed the portable phone her son had given her last year. He’d programmed it, too. She didn’t have to dial a number, just press 1, 2, or 3. The number 1 on the dial was Jonathan himself, the triplets were number 2, and Harry Nathan, her doctor, was number 3. It was unlikely anyone would call her. Jonathan was too busy, or so he said, and the triplets called every day at noon, so they wouldn’t be calling again at night. Harry Nathan never called. Secretly she suspected he couldn’t remember she was his patient. She really needed to think about getting a new doctor, a young, savvy one who didn’t creak and moan and groan. All the rest of her friends were either gone or living in retirement villages, hoping relatives would visit or call. At least once in a while.

If she kept this up, she was going to start feeling sorry for herself, then she would end up crying herself to sleep.

Maybe if she’d listened to her own advice, she wouldn’t have cried and wouldn’t have slipped on the braided rug by the sink when she went to get the portable phone. One second she was standing upright, the phone in her hand, the next she was on the floor, her arm pinned under her chest. Pain ricocheted up her arm.

She knew her arm was probably broken. In the time it took her heart to beat twice, she knew her life was never going to be the same. Freddie licked Loretta’s face and whimpered at her side.

God in heaven, what will happen to my beloved dog?

She did her best to slide backward so that her back rested against the cabinet under the sink.

With her good hand she placed the portable phone in her lap, her finger tracing the numbers. She pressed the number 3 and waited until she heard Harry Nathan’s reedy voice. “It’s Loretta, Harry. I think I broke my arm. I’m going to need some medical attention. Of course I want you to come out here. I’m blind with cataracts, Harry, or did you forget? Do you expect me to get in a car and drive to you? Of course I’ll wait for you. Where could I possibly go?”

Loretta drew a deep breath before she pressed the number 1. She really didn’t think her son would be home, and he wasn’t. She left a message. She wouldn’t call the triplets because they’d drop everything, pile into their car, and drive there at ninety miles an hour. They would do it because they loved her. She wondered, as she struggled with the pain, how long it would take her son to arrive.

If

he arrived.

Freddie barked thirty minutes later at the sound of a car pulling up to the house, but she didn’t leave her mistress’s side.

Harry Nathan was a small, stooped man, with a short beard and wire-rimmed glasses. He looked down at his patient. “This is a fine mess, Loretta. How many times this past year did I tell you to get yourself a live-in housekeeper? Well?”

Long years of familiarity allowed Loretta to snap at her doctor. “Shut up, Harry, and help me. I guess we have to go to the clinic, is that it?”

“No, we are not going to my clinic. I’m too old to be setting bones. I’m taking you to the hospital.”

“Fine, but I’m not staying there, so get that idea right out of your head. You wait for me and bring me back here. Do we understand each other, Harry? The reason I have to come back tonight is Freddie. Swear to me, Harry.”

“All right, all right. Here, let me help you up. Now, where are your insurance cards?”

“In my purse. Put my afghan over my shoulders. I can’t put my coat on.”

Three hours later Freddie whooped her pleasure when Dr. Harry Nathan ushered his patient back into the house. “She’s rocky, Freddie, so I think we’ll let her sleep it off on this rocker,” he said, helping Loretta get comfortable.

“Loretta, I’m going to leave two pills on a saucer, and a glass of water on the hearth. You won’t have to get up that way. You’re going to have some pain, so be prepared. I want you to call me if things get bad. I’ll check on you in the morning. I’m thinking we can take those cataracts off in a few months.”