NO REGRETS ~ An American Adventure in Afghanistan (17 page)

Read NO REGRETS ~ An American Adventure in Afghanistan Online

Authors: David Kaelin

Heading out into Heart for a little site seeing. I suited up in the traditional Afghan shalwar chameez to blend in when the General had his security team take me on a tour of old Herat.

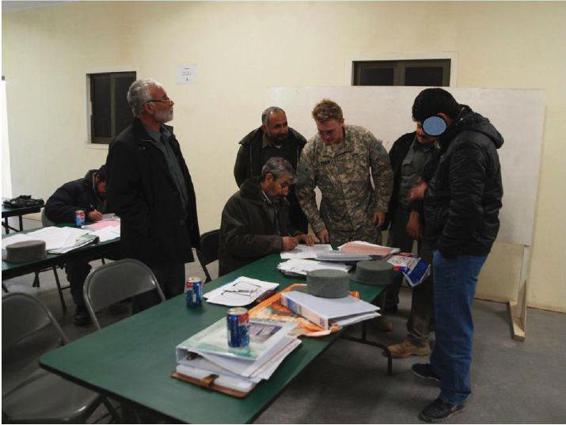

Colonel Noor Ali finalizing his books. I disguised the face of my Interpreter here to minimize the danger of being exposed to widely. Our interpreters were under constant threat of death or violence for their participation in Coalition activities.

Always one to spread Big Blue Cheer, I gave my friend Colonel Zahir a Kentucky Jersey as a departing gift. I told them that Kentucky Basketball was the official religion of Kentucky.

A gift for General Akrummuddin. I genuinely liked the General. We spent many a visit chatting together and he helped me along the way to get things done.

PART III

Herat:

The Revolutionary City

Herat is an ancient city. It was once the center of Khorasan, a historic region of the Persian Empire. By the time Alexander the Great arrived in 330 B.C. and conquered Herat—the “pearl of Khorasan”—it was a great center of culture, art, and learning. The Heratis are a spirited bunch. Once Alexander continued on in his imperial quest to see the ends of the earth, the people of Herat rose up and killed the men whom Alexander had left behind to govern them. Alexander returned and burned the city to the ground, leaving “not one stone upon the other.” Genghis Khan thundered through twelve hundred years later. He, too, would find the Heratis a rebellious people. He, too, would return to unleash his wrath upon the rebels of Herat and leave not one stone upon the other.

U.S. politicians and the media boast that Afghanistan has never been conquered. The inference being that we, the Americans, are the only nation to have done so. This was a favorite line of President George W. Bush. Herat is a perfect rebuttal of this fallacy. The city has been conquered by the Achaemenids, Alexander, Tamerlane, and the Safavids to name a few. The Afghans hate Genghis precisely because he conquered Afghanistan. Throughout its history, Herat has been a hotbed of rebellion against a myriad array of conquerors. The Russians and the British played their Great Game in Afghanistan. Herat was often a city of intrigue during these times too.

When the Soviets invaded in 1979, the people of Herat, led by Ismail Khan, rose up and rebelled fiercely. That rebellion was the spark that set off the Mujahideen war against the godless communists from the north. In the Herat revolt, the Soviets killed or wounded between 3,000 and 5,000 civilians. By the next year, the Soviet-led Afghan army had all but deserted and the Afghan Mujahideen war had begun.

America’s involvement in Afghanistan goes back some time. Josiah Harlan traveled to Afghanistan in the 1840s with the intention of becoming the “King of Afghanistan.” He settled for being named the “Prince of Ghor” before returning to the States. President Eisenhower provided a 500-million-dollar development program in the 1950s. Part of that funding went to create the Herat Airport at which I had just landed in August 2007.

The Pearl of Khorasan

Late August 2007

I didn’t know what to expect. I had boarded a civilian plane in Kabul. Seventy-five minutes later, I landed in Herat. Two SUVs pulled up as I exited the aircraft. A U.S. Army captain stepped out onto the tarmac. He waved to us. The locals and the Afghan police ignored us. We walked over to the captain who introduced himself and told us he’d be taking us to our base. After a few minutes’ delay, we grabbed our bags and were on our way.

It was a twenty-minute ride down the Herat-Farah Road from the airport. A hundred meters off the road sat Camp Stone—home of the Regional Command West (RC West). Camp Stone sat in the southwest corner of Camp Zafar that was constructed for the Afghan National Army (ANA).

Zafar

is the Dari word for “victory.” The Afghans bestowed all of their camps with names full of superlative emptiness. The Afghan National Army had victories over no one. If the U.S. or Coalition wasn’t along for the ride, the ANA simply melted away or refused to make contact with the enemy. That wasn’t victory. It was straight poor training, worse discipline, and fuckin’ cowardice.

Zach and I were going to live on Camp Stone as part of the Regional Property Assistance Team (RPAT) to the Afghan National Police (ANP). As such, we would instruct and mentor the ANP in property management and other logistics tasks. Our priority was establishing accountability for all of the equipment that was used to “shoot, move, and communicate.” That equipment was to be inventoried and accounted for across the breadth and width of Afghanistan.

We were about four years late in this effort. Coalition Forces had issued the ANP vehicles, weapons, ammunition, and communications equipment since 2003. It was rare that a loggie had been involved in the process. Grunts and gun bunnies issued equipment with little regard to inventories or records. They handed out equipment like Santa with a big red gift bag.

When I asked one of the RPAT guys how much equipment had been issued to the ANP, he said, “Dave, they’ve been issuing equipment for four years in Afghanistan. There’s little to no documentation of issues or turn-ins. No one knows what’s on hand, what’s still working, or how much of it’s been captured or lost.”

“You’re kidding?! So, you’re saying that we have no idea what’s out there?”

“That’s exactly what I’m saying. We have some records but they’re woefully inadequate.”

“I heard GAO is heading over next year to take account of our expenditures and accounting practices. There’s no way that we can be even close to prepared when they come.”

The U.S. Government Accounting Office (GAO) had been threatening to come to Afghanistan to audit Defense and State. We were told that they would be coming in 2008. In the meantime, we had a huge challenge on our hands.

“Dave, equipment has ‘disappeared’ in Qandahar only to resurface in Balkh. Equipment that we know we issued has been captured by our guys in the hands of the Taliban, the insurgents, and even at the local bazaars.”

The Army found weapons and vehicles in such remote districts as Obeh in western Afghanistan. Police outposts that were not supplied by their commands were regularly abandoned. The police stripped their uniforms, insignia, and equipment and went off the reservation. These men abandoned or sold their equipment on the black market and went absent without leave (AWOL). Insurgents captured equipment by attacking and overrunning undermanned outposts. The Taliban had our equipment. Bandits had our equipment. The stuff was everywhere. No one knew what was out there. If the shit hit the fan, we didn’t know what equipment was actually available for the Afghan police to respond. Zach and I were tasked with solving this discrepancy.

Tarjomani-Man

Early September 2007

Afghanistan has two official languages—Dari and Pashto. The Tajiks speak Dari. The Pashtuns speak Pashto. There are also a smattering of folks who speak Urdu and a few other languages heard only in this part of the world. I spoke none of these languages. To converse with the Afghans, I needed an interpreter. The Dari word for “interpreter” is

tarjoman

.

Tarjomani-man

means “my interpreter.” The

tarjoman

is a mentor’s best friend. These guys are the lowest paid of the vast army of contractors employed by the U.S. military and State Department’s mentor/training mission for the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF). Bosnian mess hall workers are paid four times as much as the average terp. The low pay hurt the quality of interpretation and translation.

Some

tarjoman

had limited vocabularies and worse comprehension. The resultant language barrier sometimes hindered the mission. With better salaries, we could have attracted more highly skilled personnel. That escaped the attention of the big bosses. They looked to cut costs and increase the profit margin at every turn.

In Kabul, the terps were selected and hired by the head shed—command headquarters. They assigned you a terp and that was that. In Herat, we were given the responsibility of hiring our own terps. We conducted the interviews and hired guys with whom we thought we’d be compatible. Incredibly, MPRI paid more than the competition. In Herat, we could actually steal the better terps from other companies. MPRI even paid almost as well as the UN.

About a week after Zach and I arrived at Camp Stone, Mick Rivas called me, “Dave, we’re interviewing terps for your team tomorrow. Be at the terp shack at 0900hrs.”

Mick made Camp Stone and Camp Zafar bearable. He was the classic senior non-com. A consummate professional, selfless, and always on the lookout for his troops. We, the MPRI field forces and attachments, were his troops. As the sergeant major mentor for the Afghan Army on Camp Zafar, Mick held the group together. He was our quartermaster, morale doctor, and an all around good guy. He was also gossipy as hell which made for great conversation. On his off hours, he could always be found in his room practicing his guitar or outside smokin’ a stogie. If you had a problem, he would do his best to help you solve it.

Mick was there to guide us through the process of hiring our terps since Zach and I didn’t know what the hell we were supposed to do or say. How would we know a good terp from a bad one? Luckily, Mick had most of the interviewing finished before we arrived. He had tested fifteen candidates on English writing, comprehension, translation, and MS Office skills. The U.S. Army is big on PowerPoint. If you work in any staff capacity, PowerPoint is essential. America’s armed forces in Afghanistan spent more time creating PowerPoint slides than mentoring or fighting on the battlefield.

After grading the terps, Mick picked the top three guys and brought them to us. He told us that if we got a good vibe, we’d hire them. If we caught a bad vibe, he would call the next interviewee until Zach and I hired three terps. We wound up hiring Rasul, Fawad, and Nasrullah that day. Fawad was a young guy dressed in what passed for fashionable clothing in Afghanistan. Rasul was a short fellow in a rumpled suit and tie. Nasrullah was a tall, thickly-built guy in traditional

shalwar chameez

or manjams—those long, baggy pants tied at the waist with a rope or a length of cloth combined with a long tunic that resembles a Victorian era night shirt. That manjam thing threw me off a bit at first. Nasrullah’s size, though, was encouraging. He was imposing looking for an Afghan. That might come in handy if we got into a hairy situation. Most Afghans whom I had met are either fat and out of shape or skinny and out of shape. Nasrullah looked like he could handle himself.