No Surrender

Authors: Hiroo Onoda

NO SURRENDER

HIROO ONODA

Translated by Charles S. Terry

BLUEJACKET BOOKS

NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS

ANNAPOLIS, MARYLAND

The latest edition of this work has been brought to publication with the generous assistance of Marguerite and Gerry Lenfest.

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

© 1974 by Kodansha International Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Published by arrangement with Kodansha International Ltd.

First Bluejacket Books printing, 1999

ISBN 978-1-61251-564-9 (eBook)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the paperback edition as follows:

Onoda, Hiroo.

[Waga RubantÅ no sanjÅ«nen senÅ. Enlgish]

No surrender : my thirty-year war / Hiroo Onoda.

p. cm.

Bluejacket books

Originally published: Tokyo : New York : Kodansha International, 1974.

1. Onoda, Hiroo.

Â

2. World War, 1939-1945âPersonal narratives, Japanese.

Â

3. World War, 1939-1945âPhilippinesâLubang Island. 4. World War, 1939-1945âArmistices.

Â

5. SoldiersâJapan Biography.

Â

6. Japan.

Â

RikugunâBiography.

Â

I. Title.

D811.05613 1999

940.54'8252âdc21

99-23484

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Print editions meet the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

12

Â

11

Â

10

C

ONTENTS

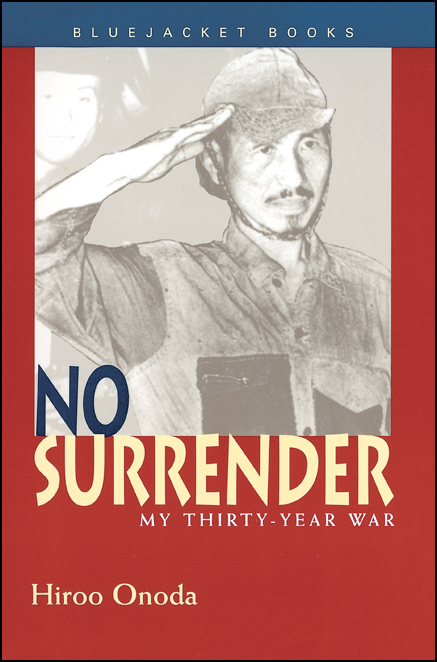

Lieutenant Hiroo Onoda was officially declared dead in December, 1959. At the time it was thought that he and his comrade Kinshichi Kozuka had died of wounds sustained five years earlier in a skirmish with Philippine troops. A six-month search organized by the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare in early 1959 had uncovered no trace of the two men.

Then, in 1972 Onoda and Kozuka surfaced, and Kozuka was killed in an encounter with Philippine police. In the following half year, three Japanese search parties attempted to persuade Onoda to come out of the jungle, but the only response they received was a thank-you note for some gifts they left. This at least established that he was alive. Owing partly to his reluctance to appear, he became something of a legend in Japan.

In early 1974, an amiable Japanese university dropout named Suzuki, who had tramped his way through some fifty countries contributing to the woes of numerous Japanese embassies, took it upon himself to make a journey through the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, Burma, Nepal and other countries that might occur to him en route. When he left Japan, he told his friends that he was going to look for Lieutenant Onoda, a panda and the Abominable Snowman, in that order. Presumably the panda and the Snowman are still waiting, because after only four days on Lubang, Suzuki found Onoda and persuaded him to meet with a delegation from Japan, which Suzuki undertook to summon.

Reports of Suzuki's meeting with Onoda touched off some of the most extravagant news coverage ever provided by Japanese press and television. People tended for a while to doubt Suzuki, but a mission was quickly dispatched to the Philippines to check on his story. Accompanying the mission were no fewer than one hundred Japanese newsmen.

There are several theories as to why the reappearance of Onoda created such a stir. Mine is that Onoda showed signs of being something that defeat in World War II had deprived Japan of: a genuine war hero. Similar excitement had arisen over earlier returnees. Only a year earlier, Sergeant ShÅichi Yokoi had come home from Guam amid great fanfare. Now, however, nobody could conceal the feeling that Yokoi was a rather ordinary manâtoo ordinary to serve as a hero. Perhaps Lieutenant Onoda would be the real thing.

It became apparent after his surrender that Onoda was intelligent, articulate, strong willed and stoic. This is the way the Japanese like their heroes to be, and in the three weeks between his first contact with Suzuki and his being received by President Ferdinand Marcos, news coverage in Japan swelled to the proportions of a deluge. When Onoda arrived back in Japan, he was received like a triumphant general. Norio Suzuki, for his part, was promoted in one jump from adventurer to assistant hero.

Normally I am almost completely immune to heroes and the adoration thereof. I also tend to be put off by publicity. Mr.Onoda himself was quoted in the newspaper I read as having said he was no hero, and I was prepared to accept that at face value. When they told me his plane would land in Tokyo at four thirty in the afternoon, my reaction was, “Well, what's to prevent it?”

Still, I am human, and when the time arrived, I put my work aside and sat in front of the set like everybody else. And when I saw this small, dignified man emerge from the plane,

bow, and then stand rigidly at attention for his ovation, I suddenly realized that he was something I had not seenâa man who was still living in 1944! Or at least only a few days out of it. A man who for the past thirty years must have been carrying around in his head the forgotten wartime propaganda of those times. Odd thoughts ran through my mind. Should I try to meet him, or had somebody else already proved to him that the American devils had no tails? Could he even now be counted upon not to commit harakiri in the palace plaza? How would he react to a Japan that is so radically different, on the surface at least, from what it was in 1944?

In short, I was hooked. With the rest of the nation I was drawn to the box off and on for a couple of weeks, watching Lieutenant Onoda greet his father and friends, Lieutenant Onoda in his hotel, Lieutenant Onoda going to the hospital for his checkup, Lieutenant Onoda having his breakfast, Lieutenant Onoda leaving Tokyo for his hometown in Wakayama Prefecture. I did not even object when the seven o'clock news on the day of his arrival gave Lieutenant Onoda's reunion with his mother top billing over an attempted hijacking then going on over our heads in Tokyo.

It became clear to me that Onoda was no ordinary straggler, but a man of strong determination and principle. Though slight of build, he looks the part of the stern, slightly pompous Japanese army officer of bygone times. I strongly felt that if he had stayed on Lubang for thirty years, he had done so for a definite reason. I wondered what it was, and what the psychology behind it was.

Even as we were all watching the television, Japanese publishers were scrambling for the rights to Onoda's story. He astonished most of them by turning down some of the more handsome offers and choosing a publisher whom he admired because of its youth magazines, which he had enjoyed in prewar times. After meeting and talking with Onoda, it seemed

to me that this decision was typical of him, for the sternness that kept him on Lubang is tempered by gentleness and nostalgia for his younger, carefree days. I personally wonder whether it was not this side of his personality that caused him to yield to a happy-go-lucky but obviously sincere Japanese youth, when he had held out against all the others.

Onoda kept neither diary nor journal, but his memory is phenomenal. Within three months of his return, he had dictated two thousand pages of recollections ranging from the most important events to the tiniest details of jungle life. In July, 1974, articles began running in serial form in the weekly

Shūkan Gendai

. Simultaneously preparations were going on for book versions in both Japanese and English, and inquiries were beginning to come in from publishers abroad.

In the course of making the English translation, I had occasion to question Onoda on a number of points, and I was amazed at the vividness with which he could describe what had taken place at a given time or how he had made some article of clothing. He himself made sketches for all of the diagrams and drawings in this book, as well as for many others appearing in a Japanese children's edition.