Noisy at the Wrong Times (33 page)

Read Noisy at the Wrong Times Online

Authors: Michael Volpe

You became the cook at Brook Green Day nursery and so thousands of children in west London grew up on lasagne, gnocchi and so many other delights unimaginable today. People of my age will still remember you, will know the smell of pasta al forno. But one job was not enough, you needed to provide us with more, be more certain that food would be on the table and that clothes were on our backs, and so you gave loyalty and dedication to others who had unimaginably more than you ever did but who never looked down on you. You would never allow that. And they loved and cherished you for your care and service.

We children grew up without the luxuries of life but we knew we were loved. You could overdo the love sometimes, Mum, I have to be honest, and it made you worry a bit more than you needed to. But we are all parents now, so maybe we understand that better than we did then. My childhood memories are full of people who passed through our lives because you chose to help them, even when they were not worthy of it. You just did that sort of thing. All my friends remember the food at our house, how you would almost force them to eat an enormous breakfast or dinner. My friend, who was named Easter, will remember how you smiled when you first met her and said “Allo, mya name is

Christamas!” I am sorry Mum, it used to really annoy you when we imitated your accent. I might do it again before I am finished. A thousand other people will remember you, because you were different, made of something so few of us are made of. You always kept your dignity and of all the things I may have ever learned from you, it was this: to keep your dignity, no matter what becomes of you. You were forgiving, generous, allowed people their failings and their mistakes. When all around you said it was a lost cause, you always gave one more chance.

And so it came to your later years, as the great joy of grandchildren arrived, when you should have been enjoying the burgeoning of new life, life that wouldn’t face the privations that your own children suffered. You went out with the kids and Lou one day, to Greenwich, Tower Bridge, the London Eye. At the end of the day you said to Lou that you had never realised London was so beautiful – that was fifty years in this city living your life looking after others, with no time for yourself. In that fifty years, even though your English was excellent, you still struggled at times with the London vernacular. When Serge once told you that he had been to see a man about a dog, you looked sternly at him and said, “I tella you Sergio, I’ma NOT having a dog in dissa house!”

But even your great spirit was overcome by your illness and we watched your very being ebb away. I remember when I realised how this great unconquerable image of you that we all had, this indestructibility, was under threat. The day was Mother’s Day, but you didn’t know it. Your body was there but we didn’t know if your spirit was or where your mind had gone to. We found it hard to visit you, because you looked but didn’t appear to see us, you listened but we never knew if you could hear us. Your grandchildren kissed you but did you feel it? If only you knew how excited Fiora was to shout “Hello nonna!” but she was four and she didn’t mind that you never answered her because she knew you were Daddy’s Mummy and had never known you any differently. The older grandchildren preferred to remember Sundays at your house, with forbidden treats secretly placed in their pockets, pasta fagioli and all of

that food. You only ever wanted your family around you, but later, when we were, did you even know we were there?

You didn’t deserve what happened to you; after all those years of hard work and sacrifice. Perhaps you finally had the tranquility that life saw fit to so frequently rob you of, that you could not feel the anxiety and worry any longer, but I wonder if maybe you would have liked nothing more than to feel it again?

You left us some time ago, Mum. We never said goodbye then because we stood at your bedside and waited for you to take your body with you. Now that you have finally gone, we can search again for those memories of the indomitable, incomparable woman you were, who would fight like a lion for us, even when we didn’t show you how grateful we were for it. We can banish the recent past and give new life to the happy memories of you that it is your absolute right that we should have above all others.

There was one blessing, Mum, when you were suffering. It was that we never had to tell you that your son Matteo had gone before you, that the boy you had shed so many tears for, suffered so much pain for, hadn’t made it, hadn’t outlived you. You would have felt that to be a failure, I know you would. But you didn’t fail, Mum, we want you to know that. If only you could have seen what we have all achieved, what your grandchildren have attained and what they have become. They will never know the hardships you knew, because you suffered them for us, and for them, and should they ever fall upon difficult times they can remember you and take from you the example of stoicism and sacrifice that you represent.

You see, Mum, I want to tell you that it was all worth it. I want to tell you that your fight was a good fight and that you won. That you had a fulfilling, worthwhile life, as noble, as distinguished and as glorious as any other. That your struggle was not in vain.

You did it Mum. You made it.

Your granddaughter Lea wrote a poem about you. Its final words I want to read to these people here because it reminds us how we should

remember you. She composed it to remind your sons of what you did for us. In it, she tells us, this child of mine, what we should know, she stands up for you and your memory, and I can hear the force in her voice as she says;

I know it feels like not even you can

Remember the sound of her voice,

But it is up to you to remember her,

And carry on singing the song she wrote

Because she wrote it for you.

It was always for you.

We will sing your song, Mum. Now go peacefully with all our love.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael, the youngest of four brothers, is from an Italian immigrant family and has three children; Leanora, Gianluca and Fiora. He is married to Sally Connew-Volpe and they live in London. Michael joined the Royal Borough Of Kensington and Chelsea in October 1989 and founded Opera Holland Park in 1996.

Michael is a Chelsea supporter, and a fervent advocate of cultural engagement for all – neither of which are necessarily related.

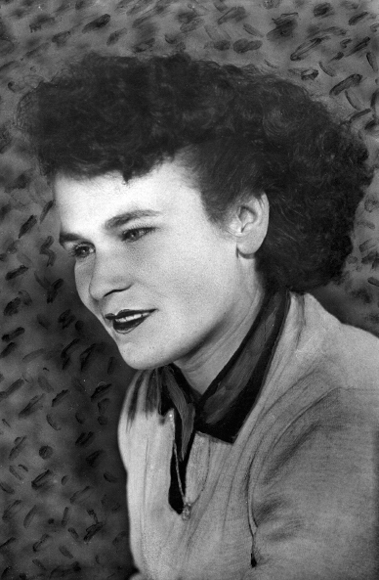

My mother, Lidia

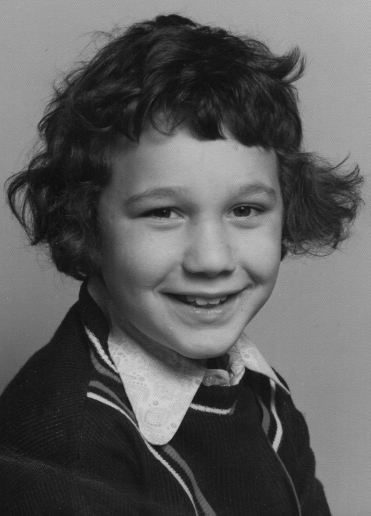

Me, sporting one of Mum’s razor-comb hairstyles

Mum and Dad with toddler Lou and baby Matt

Me, Matt and Sergio

Me at school, by the squash court

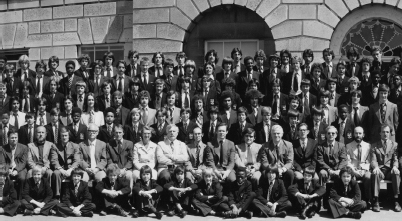

School photo, 1977. I am far right, seated on the ground. Immediately behind me is David Hudson and to his left, with hands on his knees, is Patrick Richardson

My father’s family with Nonno Luigi at the back in the white shirt