Odd and the Frost Giants (3 page)

Read Odd and the Frost Giants Online

Authors: Neil Gaiman

“W

HAT’S THAT YOU’VE GOT

there?” asked the fox.

“It’s a lump of wood,” said Odd. “My father began to carve it into something years ago, and he left it here, but he never came back to finish it.”

“What was it going to be?”

“I don’t know,” admitted Odd. “My father used to say that the carving was in the wood already.

You just had to find out what the wood wanted to be, and then take your knife and remove everything that wasn’t that.”

“Mm.” The fox seemed unimpressed.

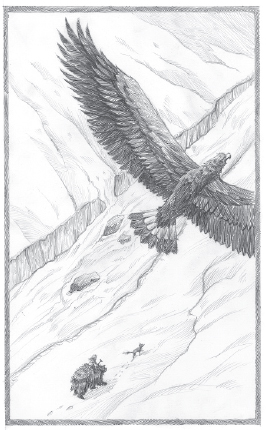

Odd was riding on the bear’s back. The fox trotted along beside them. High above them, the eagle rode the winds. The sun shone in a cloudless blue sky, and it was colder than it had been when there was cloud cover. They were heading towards higher ground, along a rocky ridge, following a frozen river. The wind hurt Odd’s face and ears.

“This won’t work,” said the bear gloomily. “I mean, whatever it is, it won’t.”

Odd said nothing.

“You’re smiling, aren’t you,” said the bear. “I can tell.”

The thing was this: You got to Asgard, the place

the Gods came from, by crossing the Rainbow Bridge, which was called Bifrost. If you were a God, you simply wiggled your fingers and a rainbow appeared, and you walked across it.

High above them, the eagle rode the winds.

Easy

, or so the fox said, and the bear morosely agreed. Or at least, it

was

easy until you didn’t have fingers. Which they didn’t. Still, even if you didn’t have fingers, Loki pointed out, you could normally still find a rainbow and use it. Rainbows turned up after it rained, didn’t they?

Well, they didn’t in midwinter.

Odd thought about it. He thought about the way rainbows appeared on rainy days, when the sun came out.

“I think,” said the bear, “as a responsible adult, I should point a few things out.”

“Talk is free,” said Odd, “but the wise man chooses when to spend his words.” It was

something his father used to say.

“I just thought I should point out that we are wasting our time. We don’t have any way of getting to the Rainbow Bridge. And if by some miracle we crossed it, look at us—we’re animals, and you can barely walk. We can’t defeat Frost Giants. This whole thing is hopeless.”

“He’s right,” said the fox.

“If it’s hopeless,” said Odd, “why are you coming with me?”

The animals said nothing. The morning sun sparkled up at them from the snow, dazzling Odd, making him squint.

“Nothing better to do,” said the bear after a while.

“Up here!” said Odd. He clung tightly to the bear’s fur as they clambered up the side of a steep hill. They could see the mountains beyond.

“Stop,” said Odd. The waterfall was one of his favorite places in the world. From spring until midwinter it ran high and fast before it crashed down almost a hundred feet into the valley beneath, where it had carved out a rocky basin. In high summer, when the sun barely set, the villagers would come out to the waterfall and splash around in the basin pool, letting the water tumble onto their heads.

Now, the waterfall was frozen and ice ran from the crags down to the basin in twisted ropes and great clear icicles.

“It’s a waterfall,” said Odd. “We used to come out here. And when the water came down and the sun was shining brightly, you could see a rainbow, like a huge circle, all around the waterfall.”

“No water,” said the fox. “No water, no rainbow.”

“There’s water,” said Odd. “But it’s ice.”

He took the axe from his belt, pushed his crutch beneath his arm as he got down from the bear’s back and walked over the ice until he stood before the frozen waterfall. He used the crutch to hold himself in position as best he could. Then he began to swing the axe. The noise of the blade hitting the thick icicle cracked off the hills around them, making echoes that sounded as if an entire army of men was hammering on the ice…

There was a crash, and an icicle as large as Odd smashed down to the surface of the frozen pool.

“Clever,” said the bear, in the kind of tone of voice that meant that it wasn’t clever at all. “You broke it.”

“Yes,” said Odd. He inspected the shards of ice on the ground, picked up the biggest, most

cleanly broken piece he could find, then took it to the side of the frozen pool, and put it on a rock, and stared at it.

“It’s a lump of ice,” said the fox. “If you ask me.”

“Yes,” said Odd. “I think the rainbows are imprisoned in the ice when the water freezes.”

The boy took out his knife and began to trace outlines on the ice block with the blade, going back and forth with it, scoring it as best he could.

The eagle circled high above them, almost invisible in the midwinter sun.

“He’s been up there a long time,” said the bear. “Do you think he’s looking for something?”

The fox said, “I worry about him. It must be hard to be an eagle. He could get lost in there. When I was a horse…”

“A mare, you mean,” said the bear with a grunt.

The fox tossed its head and walked away. Odd put his knife down and took out his axe once more. “I’ve seen rainbows on the snow sometimes,” said Odd, loud enough for the fox to hear, “and on the side of buildings, when the sun shone through the icicles. And I thought, Ice is only water, so it must have rainbows in it too. When the water freezes, the rainbows are trapped in it, like fish in a shallow pool. And the sunlight sets them free.”

Odd knelt on the frozen pond. He hit the big lump of ice with his axe. This did nothing—the axe just glanced off the ice and nearly cut into his leg.

“Do that again and you’ll break the axe,” said the fox. “Hold on.”

He nosed along the bank of the frozen pool for several minutes. Then he began scrabbling at the snow. “Here,” he said. “This is what you need.” He put his paw on a grey rock he had revealed.

Odd pulled at the stone, which came up easily from the ground, and it proved to be a flint. Part of it was grey, but the other part, the translucent part of the flint, was a deep salmon-pink color, and it seemed to have been chipped.

“Don’t touch the edges,” said the fox. “It’ll be sharp. Really sharp. They didn’t mess about when they made those things, and they don’t blunt easily if you make them well.”

“What is it?”

“A hand axe. They used to do sacrifices here, on that big rock over there, and they used tools like this to slice up the animal and to part the

flesh from the bones.”

“How do you know?” asked Odd.

There was satisfaction and pride in the fox’s voice as it said, “Who do you think they were making sacrifices to?”

Odd brought the tool over to the lump of ice. He ran his hands over the ice, slippery as a fish, then he began to attack the ice with the flint. The rock felt warm in his hands. Hot, even.

“It’s hot,” said Odd.

“Is it?” said the fox, sounding pleased with itself.

The ice fell away under the flint axe, just as Odd had wanted it to. He hacked it into a shape that was almost triangular, thicker on one side than on the other.

The fox and the bear stood nearby watching. The eagle descended to see what was going on,

landed in the leafless branches of a tree and was still as a statue.

Odd took his ice triangle and placed it so that the sunlight shone through it onto the white snow that drifted on the frozen pool. Nothing happened. He twisted it, tilted it, moved it around and…

A puddle of light appeared on the snow, all the colors of the rainbow…

“How is that?” asked Odd.

“But it’s on the ground,” said the bear doubtfully. “It should be in the air. I mean, how can

that

be a bridge?”

The eagle took off from the tree with a clap of wings, and began to fly upwards.

“I don’t think he’s very impressed,” said the fox. “Nice try.”

Odd shrugged. He could feel his mouth pulling

up into a smile even as his heart sank. He had been so proud of himself, making a rainbow. His hands were numb. He hefted the stone axe, was about to throw it, hard, away from him and then simply dropped it.

A screech. Odd looked up to see the eagle plummeting towards them. He began to step back, marvelling at the eagle’s speed, wondering how the bird could pull out in time…

It didn’t pull out.

The eagle hit the patch of colored light on the white snow without slowing, as if it was diving into a pool of liquid water.

The puddle of color splashed…and

opened.

Scarlet fell softly about them and everything was outlined in greens and blues and the world was raspberry-colored and leaf-colored and golden-colored and fire-colored and blueberry-colored

and wine-colored. Odd’s world was colors, and, despite his crutch, he could feel himself falling forward, tumbling into the rainbow…

Everything went dark. Odd’s eyes took moments to adjust, and when they did, above him was a velvet night sky, hung with a billion stars. A rainbow arced across it, and Odd was walking on the rainbow—no, not walking: his feet did not move. It felt as if he was being carried up the arch, going upwards, forwards, uncertain how fast he was travelling, only certain that he was somehow swept up in the colors and that it was the colors of the rainbow that were carrying him along.

He looked behind him, wondering if he would see the snowy world he had left, but he saw nothing but blackness, empty even of stars.

Odd’s stomach gave a sort of a lurch. He could

feel himself dropping, and he turned his head to see the rainbow fading. Through the prism of colors he saw huge fir trees, foggy and purple and blue and red, and then the trees came into focus and found their own color—a cool bluish green—as Odd tumbled off the side of a fir tree and down into a drift of snow. The scent of bruised fir tree surrounded him.

It was daylight. He was wet, and cold, but unhurt.

He glanced up, but there was no sign of the Rainbow Bridge. Silently, across the thick snow, the fox and the bear were walking towards him. And then, with a rattle and a clatter, the eagle landed on a branch beside him, making the snow on the branch fall

flump

to the ground. The eagle looked less crazy now, thought Odd. And then,

it looks bigger.

“Where is this place?” asked Odd, but he knew the answer, knew it even before the eagle threw back its head and screamed, with delight and with relish and with keen, dark joy, “Asgard!”

R

EALLY, TRULY, WITH ALL

of his heart, Odd found that he wanted to believe that he was still in the world he had known all his life. That he was still in the country of the Norse folk, that he was in Midgard. Only he wasn’t, and he knew it. The world smelled different, for a start. It smelled

alive

. Everything he looked at looked sharper, more real, more

there

.

And if there was any doubt, then he only had to look at the animals.

“You got bigger,” he told them. “You’ve grown.”

And they had. The fox’s ears were now level with Odd’s chest. The eagle’s wingspan, when the bird preened in the sunshine, was as wide as a longship. The bear, which had not been small to begin with, was now the size of Odd’s father’s hut, enormous in its bulk and in its bearishness.

“We didn’t grow,” said the fox, its fur the vivid orange color of a blazing fire. “This is how big we are here. We’re normal-sized.”

Odd nodded. Then he said, “So this whole place is called Asgard, and the town we have to go to is also called Asgard, yes?”

“We named it after ourselves,” said the bear. “After the Aesir.”

“How far is it to your place?”

The fox sniffed the air, then it looked around. There were mountains behind them, and a forest all about them. “A day’s travel. Maybe a little more. Once we get through this forest we reach the plain, and the town is in the center of the plain.”

Odd nodded. “I suppose we should get on with it, then.”

“There will be time,” said the bear. “Asgard is not going anywhere. And right now, I am hungry. I am going fishing. Why don’t you two build us a fire?” And without waiting to see what would happen, the great beast lumbered off into the darkness of the forest. The eagle flapped its wings, loud as a small thunderclap, and it took off, circling higher and higher, and then followed the bear.

Odd and the fox gathered wood, finding dry twigs and dead branches, then Odd heaped them high. He took out his knife and sliced a point on a hard stick, put the point against a piece of dry, soft wood, preparing to rotate the stick between his hands, to use the friction to make a fire.

The fox eyed him, unimpressed. “Why bother?” it said. “This is easier.” It put its muzzle against the heap of wood, breathed on the twigs. The air above the twigs wavered and shimmered, then, with a crackle, the sticks caught fire.

“How did you do that?”

“This is Asgard,” said the fox. “It’s less…solid…than the place you come from. The Gods—even transformed Gods—well, there is power in this place…you understand?”

“Not really. But not to worry.”

Odd sat beside the fire and he waited for the

bear and the eagle to return. While he waited, he took out the piece of wood his father had started to carve. He inspected it, puzzling over the shape, familiar yet strange, wondering what it had been intended to be, and why it should bother him so. He ran his thumb over it, and it comforted him.

It was twilight by the time the bear brought back the largest trout Odd had ever seen. The boy gutted it with his knife (the fox devoured the raw guts enthusiastically), then he speared it through with a long stick, cut two forked sticks to make an improvised spit and he roasted it over the fire, turning it every few minutes to ensure it did not burn.

When the fish was cooked, the eagle took the head, and the other three divided the meat between them, the bear eating more than the

other two put together.

The twilight edged imperceptibly into night, and a huge, dark-yellow moon began to rise on the horizon, achingly slowly.

When they had finished eating, the fox went to sleep beside the fire, and the eagle flapped heavily off into a dead pine to sleep. Odd took the leftover fish and pushed it into a drift of snow, to keep it fresh, as his mother had taught him.

The bear looked at Odd. Then it said casually, “You must be thirsty. Come on. Let’s look for some water.”

Odd climbed onto the bear’s broad back, and held tight as it lumbered off into the darkness of the forest.

It didn’t feel like they were looking for anything, though. It felt like the bear knew exactly where he was going, that he was heading somewhere. Up a

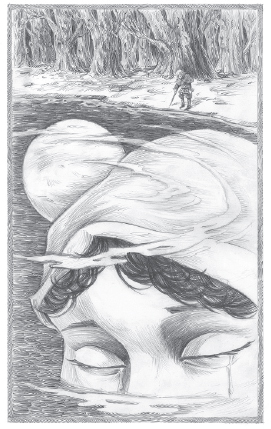

ridge and down into a small gorge and through a copse of trees, magical in its stillness, and then they were pushing through scratchy gorse, and now they were in a small clearing, in the center of which was a pool of liquid water.

“Careful,” said the bear, quietly. “It goes down a long way.”

Odd stared. The yellow moonlight was deceptive, but still…

“There are shapes moving in the water,” he said.

“Nothing in there that will hurt you,” said the bear. “They’re just reflections, really. It’s safe to drink. I give you my word.”

Odd untied his wooden cup from his belt. He dipped it into the water, and he drank. The water was refreshing and strangely sweet. He had not realized how thirsty he had been, and he filled

and emptied his wooden cup four times.

And then he yawned. “Feel so sleepy.”

“It’s all the travelling,” said the bear. “Here. Let me.” It pulled over several fallen fir branches at the edge of the clearing with its teeth. “Curl up on these.”

“But the others…” said Odd.

“I’ll tell them you fell asleep in the woods,” said the bear. “Just don’t go wandering off. For now, just rest.”

And the bear lay down on the branches, crushing them under its bulk. The boy lay beside the animal, smelling the deep bearish scent of it, pushing against the fur and feeling the softness and the warmth.

The world was comfortable and quiet and warm. He was safe, and everything was enclosed by the dark…

When he opened his eyes once more, he was cold, and he was alone, and the moon was huge and white and high in the sky.

More than twice as big as the moon in Midgard

, thought Odd, and he wondered if that was because Asgard was closer to the moon, or whether it had its own moon…

The bear was gone.

In the pale moonlight Odd could see shapes moving in the water of the pool, and he pulled himself to his feet and limped over to look more closely.

At the water’s edge he crouched down, made a cup from his hand, scooped up water, and drank. The water was icy cold, but as he drank he felt warmed and safe and comfortable.

The figures in the water dissolved and reformed.

“What do you need to see?” asked a voice from behind Odd.

Odd said nothing.

“You have drunk from my spring,” said the voice.

“Did I do something wrong?” asked Odd.

There was silence. Then, “No,” said the voice. It sounded very old, so ancient Odd could not tell if it was a man’s voice or a woman’s. Then the voice said, “Look.”

On the water’s surface he saw reflections. His father, in the winter, playing with him and his mother—a silly game of blindman’s buff that left them all giggling and helpless on the ground…

He saw a huge creature, with icicles in its beard and hair like the pattern the frost makes on the leaves and on the ice early in the morning, sitting

beside a huge wall, scanning the horizon restlessly.

He saw his mother sitting in a corner of the great hall, sewing up Fat Elfred’s worn jerkin, and her eyes were red with tears.

He saw the cold plains where the Frost Giants live, saw Frost Giants hauling rocks, and feasting on great horned elk, and dancing beneath the moon.

He saw his father, sitting in the woodcutter’s hut he had so recently left himself. His father had a knife in one hand, a lump of wood in the other. He began to carve, a strange, distant smile on his face. Odd knew that smile…

He saw his father as a young man, leaping from the longship into the sea and running up a craggy beach. Odd knew that this was Scotland, that soon his father would meet his mother…

He saw his mother sitting in a corner of the great hall…and her eyes were red with tears.

He kept watching.

The moonlight was so bright in that place. Odd could see what he needed to. After some time, he pulled out the lump of wood he had found in his father’s hut and his knife, and he began to carve, in smooth, confident strokes, removing everything that wasn’t part of the carving.

He carved until daybreak, when the bear crunched through the trees into the clearing.

It did not ask what Odd had seen in the pool, and Odd did not volunteer anything.

Odd climbed onto the bear’s back. “You’re getting smaller again,” said Odd. This was no longer the huge bear of the previous evening. Now it seemed only slightly bigger than it had been the first time Odd had ridden it. “You’ve shrunk.”

“If you say so,” said the bear.

“Where do the Frost Giants come from?” asked

Odd, as they bounded through the forest.

“Jotunheim,” said the bear. “It means

giants’ home.

It’s across the great river. Mostly they stay on their own side. But they’ve crossed before. One time, one of them wanted the Sun, the Moon and Lady Freya. The time before that, they wanted my hammer, Mjollnir, and the hand of Lady Freya. There was one time they wanted all the treasures of Asgard and Lady Freya…”

“They must like Lady Freya a lot,” said Odd.

“They do. She’s very pretty.”

“What’s it like in Jotunheim?” asked Odd.

“Bleak. Treeless. Cold. Desolate. Nothing like it is here. You should ask Loki.”

“Why?”

“He wasn’t always one of the Aesir. He was born a Frost Giant. He was the smallest Frost Giant ever. They used to laugh at him. So he left.

Saved Odin’s life, on his travels. And he…” The bear hesitated and seemed to think twice about whatever he had been going to say, then finished, “…he keeps things interesting.” And then the bear said, “Anything that you did last night, anything you saw…”

“Yes?”

“The wise man knows when to keep silent. Only the fool tells all he knows.”

The fox and the eagle were waiting beside the remains of the fire. Odd finished what was left of the fish. Then the bear said, “Well? What do we do now?”

Odd said, “Take me to the edge of the forest. You wait for me. I’ll walk alone from there to the gates of Asgard.”

“Why?” asked the fox.

“Because I don’t want the Frost Giants knowing

you three are back,” said Odd. “Not yet.”

They set off.

“I could get very used to travelling by bear,” Odd said. But the bear only grunted.