Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers (17 page)

Read Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers Online

Authors: Lillian Faderman

Tags: #Literary Criticism/Gay and Lesbian

Such pressure to be heterosexually active brought with it in more conventional circles a concomitant pressure to eschew whatever could be characterized as homosexual, including whatever remnants were left of the old institution of romantic friendship. While such homophobia represented just one more taboo to be joyously flaunted by the adventurous and the experimental, it must have been confusing to many, especially when the popular sex reformers managed to sound modern and revolutionary while promoting antihomosexual prejudice, warning that maintenance of what they called “outworn traditions” regarding virginity was manufacturing what they called “perverts.” Their advice to women, that the only true happiness lay in heterosexual fulfillment, was a far distance from the work of supposedly conservative, traditional writers of earlier centuries such as William Alger, who had advised in his 1868 book

The Friendships of Women

that unmarried females (whose numbers had increased because so many men were killed during the Civil War) would do well to form romantic friendships with other women, since those relationships bring to life “freshness, stimulant charm, noble truths and aspirations.”

52

In contrast, during the post World War I years, when for the first but not the last time in this century men came back to reclaim their jobs and their roles, it was insisted that virtues such as Alger delineated were to be found not in romantic friendships but in “companionate marriage” alone. Companionate marriage, which now became an American ideal, was supposed to rectify the most oppressive elements of Victorian wedlock; marriage would become an association of “companionship” and “cooperation,” although real social equality between men and women was not a concern that its advocates addressed. As a means of achieving the goals of companionate marriage, numerous marriage manuals and other texts on how to attain happiness pressured men to perform sexually, to bring their mates to orgasm and contentment. If they were unsuccessful, the blame was attributed not only to their “performance skills” but also to the woman’s “failure to transfer the libido from a love object of the same sex to one of the opposite sex.”

53

Since in earlier eras “decent” women were generally not expected to respond to men sexually, no such “explanations” for unresponsiveness had been sought and it was unlikely that lesbianism would have been suspected as a reason for heterosexual unhappiness. By the 1920s, however, the notion that love between women could stand in the way of marital happiness instead of being “a rehearsal in girlhood” for such happiness, as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow had characterized it in 1849, was so popularized that Broadway audiences flocked to see Edouard Bourdet’s

The Captive,

the

succes de scandale

play devoted to that theme. Lesbianism thus became the villain in the drama of bringing men and women together through (hetero)sexual freedom and companionate marriage (in which the female companion was implored to stay put in the kitchen and the bedroom). As villain of the piece, the lesbian gradually came to be characterized by a host of nasty moral attributes that were reflected in literature and popular culture for the next half century.

The sexual revolution of the 1920s, which was felt throughout cosmopolitan areas but most particularly in offbeat centers such as bohemian Greenwich Village and tourist Harlem, had two important effects on love between women of middle-class backgrounds in particular: to some of them who were just beginning to define themselves consciously as sexual beings, an erotic relationship with another woman was one more area to investigate and one more right to demand, though quietly compared to the vociferous demands fifty years later. Unlike romantic friends of other eras, who would have happened upon lesbian genital sexuality only by chance if at all, their counterparts of the ’20s

knew

all about the sexual potential that existed between females. Having been given concepts and language by the sexologists—from Krafft-Ebing to Ellis to Freud—they could consciously choose to explore that potential in ways that were not open to their predecessors. And the temper of the times often

seemed

to give them permission for such exploration.

On the other hand, the times were not, after all, far removed from the Victorian era, and despite seeming liberality, the notion of sex between women was too shocking a departure from the past image of womanhood to be widely tolerated. Nor could the sexual potential of women’s love for each other be ignored now by those outside the relationship as it could be earlier. American men realized with a shock that if they wanted the benefits of companionate heterosexuality, which sexologists and psychologists told them was crucial to well-being, they needed to suppress women’s same-sex relationships—which had almost always been companionate and therefore rivaled heterosexuality. Thus, ironically, in the midst of a sexual revolution when sex between women became an area of erotic exploration in some circles and some women were beginning to establish a lifestyle based on that preference, lesbians came to be regarded as pariahs.

Mary Fields, born a slave in 1832, often wore men’s clothes as a stagecoach driver. (From

Black Lesbians

by J. R. Roberts, Naiad Press, 1981; reprinted by permission.)

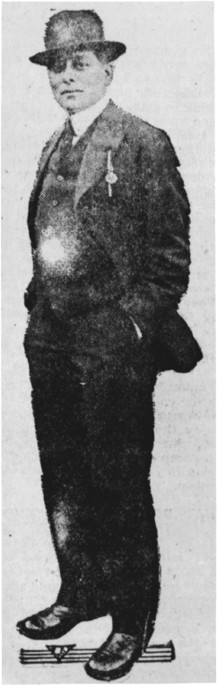

Ralph Kerwinieo, nee Cora Anderson, an American Indian woman: “The world is made by man—for man alone.” (From

The Day Book,

1914; courtesy of Jonathan Ned Katz.)

Doctor Bernard Talmey observed in 1904 that the American public’s innocence regarding lesbianism resulted in dubbing women’s intimate attachments with each other “mere friendship.” (Courtesy of the Found Images Collection, Lesbian Herstory Archives/ L.H.E.F., Inc.)

Songwriter George Hannah observed of World War I that Uncle Sam: “Packed up all the men and sent ’em on to France,/Sent ’em over there the Germans to hunt, /Left the women at home to try out all their new stunts.” (Courtesy of the Found Images Collection, Lesbian Herstory Archives/L.H.E.F., Inc.)

Women Physical Education majors at the University of Texas held private “drag” proms in the 1930s. (Courtesy of Olivia Sawyers.)

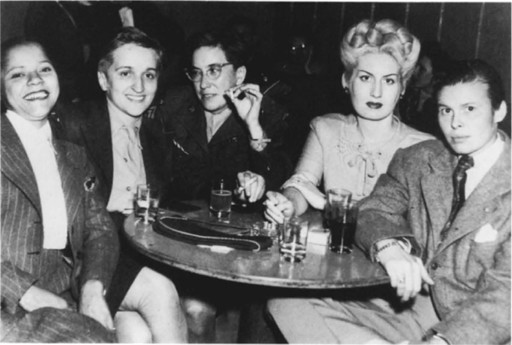

New York, 1940s. Middle-class minority lesbian styles were diverse. (© Cathy Cade,

A Lesbian Photo Album,

1987. Reprinted by permission.)

San Francisco, circa 1944. A private lesbian party. (Courtesy of the June Mazer Lesbian Collection, Los Angeles.)