Of Beetles and Angels (5 page)

I guess God must have heard my brother, because He sent some friends down to help him. A van pulled up, carrying four tall black guys. They looked like high-school students, maybe older. They strutted toward Jake with dangerous confidence.

“What’s going on here? Does someone have a problem with our brother?”

No answer. Confronted with someone larger than himself, the school bully became the school coward.

“Why are you so quiet now, you little punk? Yeah, you. Don’t look around like I’m talking to somebody else. I’m talking to you. If you touch this kid today or any other day, you’re dead meat. You got that? Good. Now get the heck outta here.”

Jake and his friends slunk away, never to be heard from again. They understood violence and they understood threats.

Those four rescuers? They were the older brothers of Tewolde’s friend Kawaun. Kawaun had told his brothers that all the white burnouts were getting together to gang up on his black friend, and his brothers had come down to help the black kid out.

When we were still in elementary school, my brother told me the most hilarious stories at night. They usually starred these five Chinese brothers who had moved to the United States. Each brother had his head shaved in the front and long hair in the back, sometimes braided. All five brothers lived together.

Tewolde spun his stories from the top bunk and I heard them in the bottom. They always featured the same plot: The five Chinese brothers craved peace and usually tried to mind their own business. But some ill-willed Americans would always mistreat them.

Like all Chinese people, the Chinese brothers had mastered kung fu, karate, and every other martial art. My brother and I believed this about Chinese people because of a TV show called

Samurai Sunday

that came on right after church. All the Chinese people in that show could really fight.

Tewolde’s Chinese brothers would be doing something innocent, such as watering their garden, and then, out of nowhere, their neighbors would insult them or hurl a rock through their window. Having no choice, the Chinese brothers would use their kung fu to beat up the Americans.

Eventually, it got so bad that the brothers had to whoop the whole town; every last citizen, five citizens at a time. It was a lot of work, but the brothers had no choice.

Sometimes I wonder why my brother and I loved the Chinese brother stories. I used to think it was because they were funny. Lately, though, I have come to believe that the brothers were more than stories. They were our kid way of dealing with our unfriendly world.

Even if we couldn’t beat up all of the cruel kids at school, the five Chinese brothers could. They could whip the kids, they could whip their parents, they could whip the entire town.

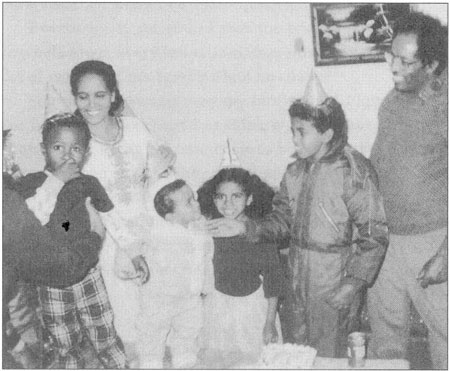

Celebrating Hntsa’s birthday the American Way. From left to right: A family friend, Tsege, Hntsa, Mehret, Tewolde, and Haileab.

AYS OF

M

ISCHIEF

B

ack in Sudan, on a day each year that every kid looked forward to, our little village erupted into a sea of flames.

We built a huge bonfire in the middle of the village. We gathered thick sticks and dipped them into the fire, pulling them out only after they had blazed into torches. Then we raced together from adobe to adobe.

Muslims and Christians, Eritreans and Ethiopians, bullies and prey — on this night, all of us forgot our differences and united. We ran from adobe to adobe, waving our torches fearlessly, chanting out our ancestors’ cry:

Hoyo Hoyo, Hoyo

Hoyo Hoyo, Hoyo

Akho akhokay, Berhan geday

Berhan neibel, Hoyo,

Himaq wisa, Hoyo,

Quincha wisa, Hoyo,

Tekwon ito, Hoyo.

Oh, new year, let it be a good one, all the evil leave us, let peace join us, let harvest come.

Our parents waited for us at their adobes and chimed in enthusiastically when we approached,

“Hoyo Hoyo, Hoyo! Hoyo Hoyo, Hoyo!

”

They told us that in the old days, in the old country, before the rise of Mengistu and the Dergue and desolation, adults had passed out presents to the children during

Hoyo Hoyo

— money, candy, food, and even homebrewed liquor for the older kids.

But in our refugee camp, no one could afford to give presents to so many.

Presents or no, we still loved

Hoyo Hoyo.

On this one day, we embraced what we most feared on other days.

You can’t hurt us today, oh, fire. We say IMBEE! NO YOU CAN’T! Go ahead. Burn us and our adobes. Take our chickens and goats, and even our gardens.

For today, we are not refugees, we don’t live in adobes. No, we live back home among our people, and we celebrate our new year, and we dance with you like our forefathers before us.

When we came to America and heard of a strange holiday where children morphed into all manner of strange creatures, my siblings and I were puzzled. But eventually, we understood. This was their version of

Hoyo Hoyo.

Just like we did, they roamed from house to house and brought smiles to adults. Instead of

Hoyo Hoyo,

they chanted “Trick or treat!” Instead of fire, they flouted vampires, witches, and all of Hell’s creatures.

Our refugee village in Sudan could not afford presents, but this country gladly showered candy, fruit, even money on its petitioners. And not just a little bit of candy, but almost unlimited free candy — beyond our wildest dreams!

Declaring Halloween our favorite holiday, we convinced our parents that they should allow us to go trick-or-treating alone. By the second year, we had our strategy all figured out.

We raced all the way home from school through Wheaton’s quiet streets, arriving home before any of our classmates. After ransacking our parents’ closet for two pillowcases, we started out on our way — usually with hastily designed costumes. One year, I took a grocery-sized paper bag, poked two holes in it, and dubbed myself “Paper-Bag Man.”

We had two rounds. During the treasure round we did not knock on any doors. We ran from house to house, searching eagerly for baskets labeled “Please take one.” Without pausing, we snatched the baskets and dumped all of their contents into our bags.

We wondered sometimes, did adults really expect unsupervised kids to take only one piece of candy? What self-respecting kid would do such a thing?

We started round two right as most kids started their regular trick-or-treating. We joined them in running from house to house, crying out with our

habesha

accents: “Treehk ohr Treet!” We usually received our candy graciously and made sure to say “Tankooh.”

But we weren’t always nice. Each year, we singled out several round-two victims for some special fun.

One year we saw two white boys sitting on their front steps. They sat, talking softly, laughing, their bright, blond hair stirring in the early evening wind. Tewolde and I laughed as we sized them up, taking in their neatly pressed clothing and their bright, honest faces.

The straw basket they guarded dwarfed the youngest boy. But what was in it? What treasures did that basket hide? Lollipops? Tootsie Rolls? Candy bars? We hoped that it wasn’t fruit, so we wouldn’t have to throw it back at their house later.

We approached the house. When we saw the orange rectangles brimming over the basket’s top, we felt our stomachs growl. It was our favorite: Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups. There had to be one hundred Reese’s in that treasure chest. Two hundred. Who knows, it might have even been five hundred! Certainly enough for several months!

We had seen the two boys once before with their dark metallic bikes. Their bikes glimmered with an even brighter shine than new bikes; we knew that they must have spent hours every day cleaning them.

Any kid who cleaned his bike every day would be easy picking, so we approached quietly, knowing that this would be fun.

I slid around to the back of the house, keeping low, making sure they didn’t see me.

Tewolde approached the house. He stopped out on the sidewalk and motioned the kids over excitedly. “Hey, come look at this.”

The older kid hesitated a little bit. I couldn’t wait for him to go. All I needed were a few seconds.

He went.

I shot out from my hiding place, straight for the Reese’s. The younger one screamed, but it was too late. I was already dumping the basket into my pillowcase.

I couldn’t get it all because the older kid heard the scream and started to run back. Above all, I feared that their parents might come out.

But we still got about half of that candy, and I split it with Tewolde once we were several blocks away.

I couldn’t have known it then, but that older kid would one day be my best friend.

Several Halloweens after we pirated the Reese’s, our friend Kiros from the Sudanese village joined us in Wheaton. He would make Tewolde and me look like Mother Teresa.

Kiros lived with us for a few weeks and then relocated next to our Cambodian and Vietnamese refugee brothers down on Route 38, in the yellow-and-redbrick apartments that house most of Wheaton’s refugees.

We wondered, “Is he still crazy? Does he still climb huge trees and launch missiles down onto unprotected heads?”

Soon after he arrived, Kiros and I sat in the basement of my family’s home, playing

gifa,

a card game we had learned in Sudan. Playing led to cheating, cheating to yelling, yelling to card-throwing, and I arose, ready to defend myself. Kiros was no bigger than me.

But he leaped up and grabbed a plastic baseball bat. Swinging it wildly and threatening injury, he lunged at my head. He was still crazy.

After Kiros moved down to Route 38, we did not see him as often. Sometimes he vanished for weeks, even months.

But each October 31, no matter how long it had been, his thick afro always greeted us at our door after school. How he beat us home, we never quite figured out, since our schools let out at the same time and he had much farther to run. I guess he feared that we would start without him or forget about him.

The three of us started on our way. Was it us or my parents who refused to let Mehret come along? Probably my parents, since they are

habesha,

and

habeshas

never let their daughters do anything.

Rounds one and two merged into one with Kiros along. Tewolde egged us on:

“See that basket full of Snickers and Milky Ways inside the porch? That porch door looks open to me. I bet you it is — who locks their porch in Wheaton? I dare you to sneak inside and get that basket, man. Look at all those candy bars. I dare you. Do it if you’re a man.

“Watch out, Selamawi! Kiros is in! He’s pouring the candy into his pillowcase. Run, dude, run! She’s coming! He’s got the basket and the fat white woman chases him. Goo-ye! Run before her husband comes! Run before the police find us! Run or our lives will be lost! Change blocks! Jump the fence!

“Are you crazy, Kiros!? I was just kidding! All right. At least share some of that candy for all of the running we had to do because of you.”

We did many deeds that were downright dishonest, but we only felt guilty about one. And we didn’t even mean to do that one.

We had approached a house and rung the doorbell, and when that didn’t work, we started to knock on the door. Was anyone there? It was one of those long, narrow, single-level homes near the railroad tracks, and most of the lights were off.

Tewolde and I started to leave. “Wait,” Kiros said. “I see her coming. She’s coming very slowly.”

The old woman hobbled to the door, peering outside before opening it. She held an aluminum tray of candy bars.

We bowed respectfully to her and put on our best smiles. In our culture, we never harm the elderly. We revere them. We rise and give them our seats if they enter a room. We refer to them in the plural, never the singular, for they have the wisdom and deserve the respect of many.

I went first and took one piece of candy, just like she said. No Reese’s, but my second-favorite, Snickers. Tewolde went next. He reached out his hand to take another Snickers.

We never quite figured out what happened next. Maybe Kiros pushed Tewolde, maybe Tewolde slipped, maybe the old woman slipped. Whatever the cause, Tewolde knocked the tray over and the candy bars scattered, some to Tewolde’s bag, some to the grass, some to the startled woman’s feet.

We bent down to gather the candy for her. “You clumsy chump, Tewolde. What did you do?”

We were trying to help her, but the old woman, convinced that we intended to rob her, raised the aluminum tray high overhead, like Moses about to shatter the Ten Commandments.

Ranting and raving and crying all at once, the old woman smashed the metal tray on Kiros’s ‘fro with frightening force.

Kiros slumped to the sidewalk, too dizzy to move. “Get up, Kiros. Get up!” We dragged him up and fled.

The old lady hobbled after us but couldn’t catch us. How could she when she could barely walk?

We had felt guiltless in taking from those richer than us in Wheaton — maybe because taking was so much fun, or maybe because we considered ourselves modern-day Robin Hoods, taking from the rich and giving to ourselves.