Of Merchants & Heros (4 page)

TWO

I FOUND MY MOTHER

sitting at her loom, in her favourite room with the rowan-shaded window that looked out towards the distant hills.

The late sunlight, shafting through the window, was on her face, and for a moment I saw her expression of deep, hopeless sadness. But then, hearing me enter, she looked round, and seemed to drive it from her by an act of will. She stood, and extended her arms to me, and at this all my carefully prepared words left me.

Hurrying forward I cried, ‘Mother!’ and embraced her. And then, at last, the tears came.

She held herself still and silent in my embrace. I said, ‘He wrote to you.’

‘Yes,’ she said, ‘he wrote. But I knew before that. Priscus was in Rome when the news came. There was a girl travelling with you; there was a ransom demand. She was a senator’s daughter. They wanted gold.’

‘Yes,’ I said, remembering.

She eased herself away from me. She was wearing her hair tied up as she always did. Fine wisps of it spilled about her brow. There was more grey in it than I remembered.

‘As soon as he heard, Priscus cut short his visit and hurried here to tell me. But at Rome there was no word of you. It was only when I received Caecilius’s letter that I knew you were alive.’

I said, ‘Has no one else come back?’

She shook her head and looked out at the sloping lawns. ‘The consuls sent a warship to Epeiros. They found only bodies . . . or what the wolves and crows had left of them. You are the only survivor, Marcus.’

I drew my breath, and in my mind’s eye I saw once again the girl struggling with the Libyan, and stepping calmly out into the void.

The dreadful haunting thought returned that had clung to me like a sickness since that first day: that, but for my intervention, they might somehow have lived. Had I condemned them all? Was I the agent of their deaths? I furrowed my brow and tried to recall what had happened; but it was like trying to bring back the details of some demonic dream.

I sat down on the couch and put my head in my hands, and, struggling for the words, I stumbled through everything that had happened that day – the Libyan, the girl, the pirate-chief called Dikaiarchos who had killed my father. When at last I was done I looked up at her, smearing away my tears with my palms. Her eyes were dry. In a firm voice she said, ‘If you had not done what you did, you too would be dead. That is all.’

She saw me shake my head, and after a moment went on, ‘Before you were born, when I was little more than a girl, I gave birth to a child. In the first week of his life he died.’

I jerked my head up and stared, shocked out of my self-pity. ‘But . . . I never knew.’

‘No. You did not. But I am telling you now. For a long time I blamed myself, thinking there was something I should have done, or not done. In the end I grew ill, and wished for death. But my own mother, seeing this, came to me and said, “That is enough. What happened is with the gods, who see more than men, and you must not presume to know more than they. So cease, and think to the future. You have a duty, to Rome, and to your husband. You must bear him another son.” . . . And then,’ she said, ‘you were born.’

I stared at her. Her face was set. She seemed hard as stone.

Through the window I could see the red and mauve furnace of the setting sun; and, from somewhere outside, I heard one of the farmhands calling.

‘I remember Cannae,’ she said, raising her head, ‘when we thought all was lost. Carthage had defeated us, and there were those who gave up hope. Yet we survived, by our fortitude, and by believing that we should endure . . . There are times, Marcus, when courage is all you have.’

I looked down at the stone floor, chastened into silence by her cold, stern words. This was her way, as it had always been. It was the Roman way. Grief was an indulgence; and though she surely suffered, her suffering was for her alone. It seemed hard, but she had come from a hard family, brave men and brave women who through the generations had survived by facing down hardship and loss. Of all her long line of ancestors, she was not going to be the one to break.

And nor, I decided, was I.

Next day, I went around the hillside to see Priscus, our neighbour.

He and my father had known one another since they were boys. He lived alone now in his old stone farmstead, his wife having died in childbirth long before. When I was three, his only son had fallen at Trasimene, fighting against Hannibal, in the war that had lasted a generation. Such is loss. All this I had always known. Now, for the first time, I felt it.

He was a man who knew the value of silence. During those first days he would invite me to eat with him on his terrace overlooking the valley, a simple meal of beans and cabbage seasoned with some bacon, and an earthenware cup of cool wine from his own hillside vineyard. He was a gentle, white-bearded man, who seemed at peace with himself in spite of his great losses, and I found his company a comfort. He never taxed me with questions or sought explanations. If he spoke, it was of commonplace, everyday things: the land and the crops, and the passage of the seasons. He would take me walking with him along the tracks beside the fields, reminding me, now that the farm was my concern alone, that this field ought to lie fallow for a year, or another be planted with greens; or that the vines were thickening out well, but he had noticed, when he had chanced to pass that way, that the elmwood supports needed attention, or the ditches needed clearing; and might he send his steward and some of his hands to help? The days passed, and, after a fashion, I began to heal. I drove myself hard, but behind the activity, and the tiredness I felt at the end of each long day, there was a constant uneasiness I could not expel. It was like an itch I could not scratch, a greyness in my soul, an absence of I know not what.

It showed itself in ways I did not expect. The friends I had known since childhood, who lived in neighbouring farms, or in the town, seemed suddenly insipid and shallow. I had enough wit to know it was I, not they, that had changed; but I could not say what troubled me, for I did not know it myself. I felt like a man who has seen too much, like someone who has travelled down to the underworld and there beheld great horrors not fit for mortal men to see, which, returning, he can find no other who will understand.

Amidst this inner turmoil, which I could speak of to no one, I found I was happiest when I was alone. I rose each day at cock-light and worked till I was exhausted. Tiredness helped, and doing things.

But then, in the deep of the night, I would wake with a start, naked and sweating, with the cover kicked from my bed.

As the water of a pool, stirred up at first, slowly clears, so my dreams began to resolve. What troubled me was my father, or his restless shade. It was when he came to me in a dream, whole at first, then headless, mouthing words I could not hear through his white, blood-smeared lips, that I knew. Next morning, in the first grey light, while the mist still clung to the hill-slopes, I went round to the yard behind the house and took a cock from the hen-coop. I put it in a withy basket and took the path that followed the edge of the oak forest, to the little plot where our ancestors had been buried, generation upon generation, time out of mind – all except my father.

There was a shrine there, squat stone columns overgrown with ivy; and, beside it, an altar.

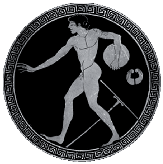

I took off my tunic and stood naked, and opening the basket I seized the bird and with my hunting knife cut its throat, letting the blood flow over the ancient stone. Then I touched the warm blood to my brow and breast, as I had seen done at a sacrifice, and extending my arms up to where the first red of dawn showed over the mountain tops, I prayed, ‘Mars the Avenger, never before have I sought anything from you. But now, if this sacrifice is pleasing, grant what I ask. The man’s name is Dikaiarchos. I do not know where he is, but gods see more than men and I need you to guide me to him. I have a debt to settle. Let me avenge my father’s death and repay blood with blood. Guide my steps, and make me the killer I must be!’

I looked up. The first darts of golden sunlight were shafting over the ridge. A bird screamed, and I saw a great tawny eagle swoop over the treetops. It dropped, then surged upwards, its wings beating the air, holding in its talons a writhing snake. The breeze stirred up the valley, rustling the oaks, and in my breast I felt power course through my body like new blood, and I knew the god had heard me.

Afterwards I went down to the stream below the orchard to wash.

I cleaned the blood away, and lay drying myself on a flat rock at the water’s edge.

Presently, from along the path, came the sound of footfalls kicking through the leaves. I propped myself up on one elbow to look, and saw Priscus ambling along the path. He raised his arm in greeting and approached.

‘Up with the dawn, I see, Marcus.’ He sat down beside me and dipped his hand in the water. ‘But isn’t it cold for swimming?’

‘It’s warm enough; but I did not come to swim.’ I fell into an awkward silence, dabbing with my foot at the chill mountain water.

He cast his eyes around. ‘Well, it is a pleasant spot, even so . . .

for whatever you were doing.’ He made to stand. ‘But I must go. I was on my way to inspect the beehives. The meadow is full of yellow flowers; the bees will like that. Perhaps, if you have finished, you would like to come along.’

I said yes, and took up my tunic from where it lay on the rock beside me. I saw his eyes move. My hunting knife was there, concealed by my clothes. I had forgotten to clean it.

‘So you have been hunting,’ he said, seeing the blood on the blade.

‘No,’ I said, ‘not hunting.’

With a frown I took the dagger and started to wash it. I had meant to keep my morning’s work to myself, but I would not lie to him. I sat back down and told him what I had done.

He listened without comment, and when I had finished he was silent for a while. Then he said, ‘And the god heard you, you say?’

‘Why yes, Priscus, I know he did. And there was a great eagle, coming from the right. And in his claws he held his prey. It is a sure sign.’

He nodded slowly to himself, and pulled a face under his white beard. I was drying my knife on a clump of grass, but seeing this I set the knife down. ‘What is it?’ I asked. ‘Do you think I did wrong?’

He shrugged. ‘It is an honourable prayer,’ he said eventually. ‘But you must be careful what you pray for.’

This irked me, and I asked him what he meant, saying I knew well enough what it was I had prayed for. ‘What is it?’ I said. ‘Do you suppose the god did not listen, or that I have offended him?’

He shook his head. ‘No, not that. You saw the eagle, and you felt the truth of it in your heart. It is in such ways that gods speak to men. No, the god heard you. But sometimes, when they grant what a man asks, they also grant what he has not foreseen.’

‘You talk in riddles,’ I said crossly, turning and pulling on my tunic. For the first time I had felt whole again. My being pulsed with the knowledge of it, and I did not want to hear his doubts. ‘Anyway, what is done is done. It is with the god now, for good or ill, so let us go and see your beehives.’

He said no more about it.

The warm weather came, and that year I turned fifteen.

I drove my body hard, and my body responded. Where once I had needed the help of the farmhands in lifting a beam, or pulling a cart, now I could do it alone. I had been a slender child, but now I thickened out. My muscles knit to my bone, and I felt my strength as something pleasing.

Whatever Priscus thought, since the day of my sacrifice to Mars the Avenger my bad dreams had ceased. I had a purpose, and that purpose was Dikaiarchos the pirate. He filled my waking thoughts, and at night I dreamt dreams of revenge, of how I would find him and kill him, and let my father’s shade drink his blood.

Soon I received another sign that the god had heard me. One day, when I happened to be searching for a tree-axe at the back of the old storeroom, I found a pile of javelins hidden behind a stack of farm tools, and, beside it, wrapped in oiled cloth, a warrior’s sword. The sword was heavy antique work, with a fine pommel of worked bronze turned to verdigris with age. My father had never mentioned it, and I guessed from its look it must have belonged to my grandfather, who had died before I was born, kept from the days when each household was its own fortress and saw to its own defence.

I cleaned up the blade and waxed the ashwood shafts of the javelins; and when I was not working I taught myself to handle them, swinging and thrusting the sword, and casting the javelins at targets in the woods.

I discovered I had a sharp eye; soon I could hit a tree trunk no wider than a man at a leaping run. As for the sword, it was too heavy for me at first; but it grew lighter as I worked at it and the muscles firmed in my arms and sides and shoulders.

A hungry man will find food where a sated man does not. And so it is with anger. It disciplined me to rise each day before dawn; it gave me strength when my body was tired; it guided my spear to a leaping hare in the forest, or a fat dove on a tree bough. And when I returned home with my prey strung over my shoulders, that prey had a name: Dikaiarchos.