On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears (43 page)

Read On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears Online

Authors: Stephen T. Asma

In addition to conservative structural views about dehumanizing media and popular culture, liberals have taken up structural views of their own, sometimes to ridiculous effect. Recall the Northern Illinois University shooter Steven Kazmierczak, who killed five others and himself and also injured eighteen in a lecture hall. Days after it happened, Mark Ames, the

author of the book

Going Postal

, published an essay on the lefty online syndication service Alternet titled “NIU: Was the Killer Crazy, or the Campus Hopeless?” The title alone represents a question about heinous crime that would not, maybe could not have been asked a few decades ago.

35

Silly, too, but telling, is the extreme structuralism to which Eldridge Cleaver (1935–1998) appealed when trying to explain his own career as a serial rapist. Cleaver is well known as an influential member of the Black Panthers (lesser known is his volte-face as a Reagan Republican in the 1980s), but before all that he was in prison for rape. In the mid-1960s he ingested enough Marxism while in jail on drug possession to bend its explanatory framework into service for other criminal transgressions. He saw himself as a victim. He and other criminals were in fact responding to a broken social system of institutional racism. Society, not the criminal, was the monster, according to Cleaver. Beyond just the degradations of the class struggle, the most insidious threat, for Cleaver, was the socially constructed set of ideals and values in our culture. Above all other such sinfully engineered ideals was “The Ogre”: “I discovered, with alarm, that The Ogre possessed a tremendous and dreadful power over me, and I didn’t understand this power or why I was at its mercy. I tried to repudiate The Ogre, root it out of my heart as I had done God, Constitution, principles, morals, and values—but The Ogre had its claws buried in the core of my being and refused to let go. I fought frantically to be free, but The Ogre only mocked me and sank its claws deeper into my soul.”

36

This horrible monster, according to Cleaver, was “the white woman.” In his poem “To a White Girl” he expressed his mixed emotions, saying that he both loved and hated the “white witch” and saw her as a “symbol of the rope and hanging tree.” In response to this torment Cleaver became a rapist as “an insurrectionary act.” By raping white women, he felt he was getting revenge for the ways that black women had been defiled by white men during the slavery era. Cleaver thus desperately tried to dress up his deviance in the clothes of righteous indignation and political revolution.

37

Setting aside these more extreme and unconvincing applications of the structural theory of monsters, we must concede the wisdom in more balanced approaches to the idea of monstrous societies. One cannot deny that certain social environments can bring out the worst in people.

The ghetto is often characterized as a Darwinian jungle of kill or be killed. Indeed, certain impoverished pockets in Chicago, Los Angeles, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and elsewhere have barbaric murder rates. In July

2007 then senator Barack Obama pointed out that nearly three dozen Chicago kids had been murdered so far that year, and that figure was higher than the casualty numbers of Illinois soldiers serving in Iraq during the same time.

Many argue that violence becomes a way of life. If you cannot adopt the violent lifestyle, you will be victimized by it. A violent criminal in Franklin, a high-security prison, said, “Normal to me is the jungle. They talk about callousness and lack of empathy, but, please, what the fuck is empathy? Where I come from, if I knock you down, you stay down. It’s not normal to come up and kill you stone dead because I want your money, but that is normality for me. At the end of the day, all of us sitting here are monsters, whether we’re armed robbers, child molesters, or killers—we’re monsters.”

38

Xavier McElrath-Bey, a Chicago native who grew up in the tough “Back of the Yards” neighborhood, an area originally made famous by Upton Sinclair’s

The Jungle

, prefers to allude to William Golding’s

Lord of the Flies

when he describes his hood. He joined a gang when he was only eleven years old, and by the time he was thirteen he had been arrested nineteen times.

39

When I met Xavier he had been out of prison for a few years, released after serving thirteen years of a sentence for murder. After serving almost half his life in prison and earning a college degree there, he had unique insights into contemporary criminality. “I don’t believe there are bad kids,” Xavier said, “just bad socialization.” When kids become teenagers, he explained, their norms and values naturally shift from those of their parents and family to those of their peer group. In his violent neighborhood, that meant becoming a gang member. “Gang life gave me a sense of purpose and meaning,” he said. The hood is a volatile and exciting place, where a young man can forge strong social ties and rise through the ranks of hierarchy and respect. The cost is a life of violence and paranoia, but it seems worth the price when you are young and successful in the lifestyle. Xavier said that he didn’t really think much about the people he was hurting, because whenever he was caught he never had to face his victims. In all his court proceedings, he heard only about “the people” or “the state” versus Xavier; he felt that he was simply breaking an impersonal law upheld by an impersonal system and an antagonistic police force.

40

Just as psychopaths lack empathy for others, here we see some of the consequences of

systems

that lack empathy or prevent empathic responses.

41

Desperate environments create desperate measures. Thug life looks monstrous by the standards of polite society, but it was hatched and nursed in a world where it has distinct advantages. According to this view, social injustice and oppression create a violent aggressive criminal culture as a

response.

42

The basic logic of this view can be seen in a different context when we consider suicide bombers. The point here is not to draw a facile comparison between ghetto criminality and suicide bombers, for they are different sorts of characters. But in today’s monsterology, they are both considered major threats to stability and they are both subjected to structural explanations. The claim that suicide terrorists are just evil monsters who freely choose to murder innocent people is alive and well. But the common belief today is that structural stresses (economic, political, ideological)

create

monstrously deviant individuals. How true, or perhaps more important, how useful is such a belief?

A study of the writings and pronouncements in the

Al-Qaida Reader

reveals no unified complaint against the United States, no specific charge that rallies and justifies suicide bomber retaliations.

43

Instead one finds a litany of localized grievances and a random body of complaints against U.S. domestic and international policy, mostly lifted from our own internal media critiques. Osama bin Laden, for example, surprisingly takes an angry interest in the refusal by the United States to sign the Kyoto agreement addressing the environmental implications of global warming, and even objects to U.S. campaign-finance laws that unfairly advantage the wealthy.

44

Reza Aslan, a scholar of Islam, interprets the pastiche nature of these grievances as evidence of a general Al-Qaida strategy to

invent

a clash of civilizations, an invention that George W. Bush’s administration was all too willing to assist in constructing. But Aslan thinks such a dramatic clash is fictional, a way of illegitimately putting one face on myriad local dissatisfactions, such as Iraqi anger at the U.S. military occupation, Palestinian anger at Israeli policies, Taliban anger at the Musharraf-Bush alliance in Pakistan, and mujahedeen anger in southern Thailand. Even if there is no one grievance that explains suicide bomber attacks on innocents, socioeconomic theorists detect common threads of poverty and lack of education. According to this view, suicide bombing results from the radical despair of crushing poverty and the humiliation of subaltern status, and therefore constitutes an insurrection by the oppressed classes. In some cases the oppressive power is domestic, but more often it is a foreign power. The 1998 militant Muslim “Declaration on Armed Struggle against Jews and Crusaders,” which was signed by bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri, argued that it was the duty of every Muslim to fight the United States and the “satanically inspired supporters allying with them.”

This interpretation of terrorism as a rebellion suggests that a removal of oppressive forces and policies will result in the end of suicide bombing. It is no stretch to see that such a view of aberrant behavior corresponds

generally to Zimbardo’s doctrine that situational forces can transform anyone into a monster. In this view, monstrous behavior becomes “rational” in the sense that it can be correlated with, if not predicted from, specific social conditions.

One of the major objections to such a view is the simple fact that a majority of the world’s poor do not blow themselves up in order to kill innocent people. In other words, the explanation is neither necessary nor sufficient. Another damaging objection is the increasing data indicating that suicide bombers are

not

as poor nor as uneducated as previously believed. The Princeton economics professor Alan Krueger has gathered data on hate crimes and terrorism since the early 1990s and claims that “the available evidence is nearly unanimous in rejecting either material deprivation or inadequate education as important causes of support for terrorism or participation in terrorist activities. Such explanations have been embraced almost entirely on faith, not scientific evidence.”

45

Analyzing data from the Pew Research Center’s 2004 Global Attitudes Project in Jordan, Morocco, Pakistan, and Turkey, Krueger found the opposite of the received view: people with higher education were much more likely to see suicide bombing as justifiable. In a study of Hezbollah martyrs (

shahids

), Krueger analyzed the life histories of 129 deceased shahids, again with surprising results: compared with the general Lebanese population, Hezbollah suicide bombers demonstrate a lower degree of poverty and a higher degree of education. Similar studies have found high levels of college education among Al-Qaida members as well.

46

But perhaps the general structural viewpoint may be maintained if we add the unique ideological ingredients of moral righteousness and afterlife rewards for martyrdom.

47

A religious fanatic might more readily kill innocents in a suicide mission if his ideological system allows him to deny the innocent status of his victims. In the same way that some ideologies allow one to redefine terrorists as “freedom fighters,” so, too, some ideologies allow one to redefine innocents as “infidels.”

Religious ideologies often dehumanize those who do not fit inside the sanctuary of orthodoxy. Some critics have argued that Islam itself is intolerant, pugilistic, and incapable of conciliation with modernity. Ayaan Hirsi Ali, a Somali Muslim apostate, assessed the tragedy of 9/11 as a tragic consequence of Islam itself: “True Islam, as a rigid belief system and moral framework, leads to cruelty. The inhuman act of those nineteen hijackers was the logical outcome of this detailed system for regulating human behavior.”

48

In this view, social and economic status does not matter so much as ideas about destiny, metaphysics, and theology.

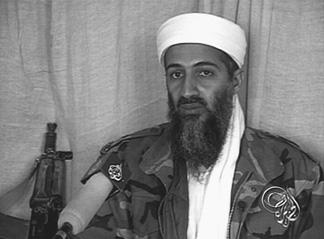

Osama bin Laden. Image courtesy of Photofest.

In 2006 Pope Benedict XVI raised the dander of many Muslims by quoting a medieval Byzantine emperor who referred to Islam as “evil and inhuman.” Despite Benedict’s claim that the disparaging comments were a quotation and not his own view, the language of a “new crusade” was resuscitated in public discourse. Osama bin Laden himself was quick to embrace crusade terminology, both in chastising the pope for stirring the pot and in promising to return the aggression. “The response will be what you see and not what you hear,” bin Laden said, “and let our mothers bereave us if we do not make victorious our messenger of God.”

49

Clerics and devotees from many different religions have bathed God’s message in blood and given credence to the theory that monstrous actions such as suicide bombings are produced by monstrous religious beliefs. One critic of religion, Sam Harris, has continued an old tradition, from David Hume to Bertrand Russell, in calling for an end of faith. In his best-selling book

The End of Faith

, he argues that suicide bombers would be almost unimaginable without the fanatical religious beliefs to motivate and justify them: “Subtract the Muslim belief in martyrdom and jihad, and the actions of suicide bombers become completely unintelligible, as does the

spectacle of public jubilation that invariably follows their deaths; insert these peculiar beliefs, and one can only marvel that suicide bombing is not more widespread.”

50

Recently Christopher Hitchens, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, and Martin Amis have lent their voices to the accusation that Islamic fundamentalism is an ideological cult of death.

51