On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears (8 page)

Read On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears Online

Authors: Stephen T. Asma

The hermaphrodite is a liminal being.

Liminal

comes from the Latin word

limen

, meaning “threshold.” When you are on a threshold, you are neither inside nor outside but in between. Hermaphrodites, with their ambiguous genitalia, are in between the traditional categories of male and female. One sees, immediately I think, that the idea of a liminal being, something between categories, is a very useful way to think about many of the subjects of this book, not just hermaphrodites. Griffins, with their ambiguous avian-quadruped shape, would qualify as liminal, as would centaurs, the chimera, the Gorgons, the Minotaur, and the Hydra. Mosaic beings, grafted together or hybridized by nature or artifice, reappear throughout the history of Western monsters as the Golem, Frankenstein’s creature, and transgenic animals. Even zombies, though not hybridized, are liminal monsters because they exist between the living and the dead. In short, liminality is a significant category for the uncategorizable. Of course, the extraordinary and the ordinary are often just different by degree rather than kind. So the extent to which

everyone

is a little hard to categorize is the extent to which we are all liminal.

Theory aside, Livy chronicled many murders of hermaphrodites in the last two centuries before the Common Era. A short sampling of his very long list will suffice to demonstrate the common perception of hermaphrodites

as monsters. In 133, “in the region of Ferentium, a hermaphrodite was born and thrown into the river”; in 119 “a hermaphrodite eight years old was discovered in the region of Rome and consigned to the sea”; in 117 “a hermaphrodite ten years old was discovered and was drowned in the sea”; in 98 “a hermaphrodite was thrown into the sea.”

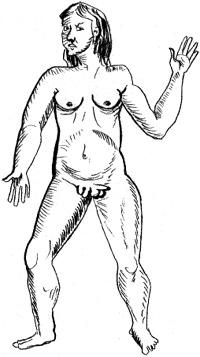

The practice of drowning hermaphrodites was extended to all seriously disabled children in the Roman Laws of the Twelve Tables. “A father shall immediately put to death a son recently born, who is a monster, or has a form different from that of members of the human race.” Pen and ink drawing by Stephen T. Asma © 2008, based on a hermaphrodite sketch in Ambroise Paré’s sixteenth-century

On Monsters

.

Many other types of monsters are cited in Livy’s encyclopedic history, including many unfortunate developmentally disabled children. A sad litany of abnormalities is offered as examples of bad omens, including conjoined twins and babies born with no hands and feet or too many hands and feet. Livy himself seems completely unmoved by any of these stories and recites them as though he’s reading sports scores. His entry for 108

BCE

reads, “At Nursia twins were born to a freeborn woman, the girl with all members intact the boy with the following deformities; in front his abdomen was open, so that the uncovered intestine could be seen, and behind he had no anal opening; at birth he cried out once

and died. The war against Jugurtha was carried on successfully.” But things seemed to be looking up for hermaphrodites, at least, by the time Pliny writes his

Natural History

. We find a refreshing tolerance developing toward hermaphrodites when he states, “There are people who have the characteristics of both sexes. We call them hermaphrodites, the Greeks

androgyny

. Once considered portents, now they are sources of entertainment.”

6

Some scholars see a teleological arc here. That is to say, the transition from superstitious murder of hermaphrodites to benign neglect and even amusement looks like progress. It looks like progress because it

is

progress, ethically speaking. But history and ethics don’t always converge on the righteous path. The classicist Luc Brisson and the gender theorist Anne Fausto-Sterling both suggest that hermaphrodites suffered terribly in the early days of Roman law, but then rational progress ultimately created a more hospitable Rome for first-century hermaphrodites.

7

But even while Pliny was assuring the reader that hermaphrodites were in the clear, so to speak, drownings continued.

8

Monsters did not simply evaporate as rational humanism came on the scene. The fear of monsters hung on in the vast stretches of darkness, while the thin flare of rationality, possessed by a few elite philosophers, swept around the terrain, without much illumination or impact.

9

The ancient story about monsters does not progress from crazy paranoia to cool-headed tolerance. Instead, superstition and rationalism shared territory, just as they do today. But it is still important to notice, even without the triumphal narrative, that cool-headed tolerance

did

evolve in the ancient world. The failure of the masses to adopt a scientific attitude toward abnormal beings does not diminish the impressive achievements of the rational minority who did. Anaxagoras’s examination of a deformed ram’s head is a good example to illustrate the uneasy simultaneity of ancient mysticism and empiricism.

The Greek historian Plutarch (46–127

CE

) chronicled the moral characters of esteemed Greek and Roman leaders. One of his subjects was the ruler of Athens in the Golden Age, Pericles (495–429

BCE

), who happened to be a good friend of the Ionian philosopher Anaxagoras (500–428). Anaxagoras, who had an unflappable character, was a great inspiration to Pericles. According to Plutarch, Anaxagoras was once accosted in the marketplace by an abusive citizen who hurled several hours of insult and even followed him to continue the diatribe outside Anaxagoras’s home.

Completely unfazed by the verbal abuse, Anaxagoras saw that it was growing dark and “ordered one of his servants to take a light and to go along with the man and see him safe home.”

10

But it was Anaxagoras’s scientific acumen that not only won Pericles’ respect but also ushered in a new phase of natural philosophy. Anaxagoras developed a mechanical theory to explain the origin and motions of the heavenly bodies, suggesting that a powerful sifting force he called

Nous

, or Mind, slowly differentiated the material soup of the early cosmos. Presaging the materialism of later atomist philosophers, he argued that every physical thing had small bits of other substances hidden within it. So the transformations in nature that we see, such as growth and decay, are really the result of these invisible mechanical processes. He looked for predictable causes, rather than superstitious divinations, and his ideas demystified the natural world.

One day Pericles heard that a monstrous ram had been born on one of his farms and he sent for the animal. When it arrived at his court, a crowd gathered around and studied the strange anomaly. The animal had only one horn growing from the center of its head. A revered fortune-teller named Lampon announced that the current political struggle between Pericles and his rival Thucydides would finally be resolved in Pericles’ favor. The monstrous ram, found on Pericles’ estate, was the auspicious sign indicating political victory. Lampon read the monster as a good omen.

Anaxagoras, who was present for the spectacle, made a careful examination of the one-horned ram and then chopped its head in half. Plutarch reports, “Anaxagoras, cleaving the skull in sunder, showed to the bystanders that the brain had not filled up its natural place, but being oblong, like an egg, had collected from all parts of the vessel which contained it, in a point to that place from whence the root of the horn took its rise.” In other words, he offered a scientific, causal explanation of the monster. A developmental glitch had produced a wonder.

Apparently this bit of demonstrable empiricism won Anaxagoras a moment of respect and admiration from the many bystanders at the court. People could actually see with their own eyes the mechanical causes of the monstrosity. But this was a very short-lived triumph of reason over superstition, because a brief time later Pericles did indeed prevail over his political rival and then Lampon the seer was the court darling all over again. This suggests, for one thing, that rational science was not exactly a juggernaut of truth, crushing the culture of superstition in its path. It also suggests that neither science nor superstition ever definitively rules out the other one. Explaining

how

a monster came to be monstrous, as Anaxagoras did, still failed to explain the monster’s

purpose

. The purpose or teleology

of monsters remained a vital concern for the ancients, and then the medi-evals, long after the mechanical explanations emerged.

This widespread cultural anxiety about the purpose of portentous monsters was partly a reflection of scientific naïveté in the uneducated classes, but more essentially it was a reflection of human nature. The Roman philosopher Lucretius, writing some three centuries after Anaxagoras, still laments the human tendency to fall into destructive emotions such as fear. Praising his philosophical mentor Epicurus (341–270

BCE

), Lucretius tells his readers that Hercules himself, and most of the other gods, were not as impressive as his rationalist hero, who banished the mental monsters of superstition. But he acknowledges the inevitable tendency for undisciplined minds to fall back into fright and trepidation. Even if monsters exist, he exclaims, they cannot really hurt you if your mind is well trained. We should fear more the internal irrational emotions.

And the rest of all those monsters slain, even if alive,

Unconquered still, what injury could they do?

None, as I guess. For so the glutted earth

Swarms even now with savage beasts, even now

Is filled with anxious terrors through the woods

And mighty mountains and the forest deeps—

Quarters ‘tis ours in general to avoid.

But lest the mind be purged, what conflicts then,

What perils, must bosom, in our own despite!

O then how great and keen the cares of lust

That split the man distraught! How great the fears!

And lo, the pride, grim greed, and wantonness—

How great the slaughters in their train! and lo,

Debaucheries and every breed of sloth!

Therefore that man who subjugated these,

And from the mind expelled, by words indeed,

Not arms, O shall it not be seemly him

To dignify by ranking with the gods?

11

Controlling the mind and controlling nature are ways for men to become god-like on this earth. Knowledge, according to the philosophers, is a great weapon against internal and external monsters. When the philosopher Thales (624–546

BCE

) was shown a centaur, he actually laughed and offered a very mundane, albeit disturbing, explanation for it.

12

A young shepherd who tended the flocks of Periander, the ruler of Corinth, brought a newborn foal to show the ruler. Jorge Luis Borges retells the humorous story in his

Book of Imaginary Beings

: “The newborn’s

face, neck, and arms were human, while the rest of its body was that of a horse. It cried like a baby, and everyone thought this a terrifying omen. The wise Thales looked at it, however, laughed, and told Periander that he should either not employ such young men as keepers of his horses or provide wives for them.”

13

Aristotle (384–322

BCE

) followed the rationalist lead of Thales and Anaxagoras, developing the most impressive and ambitious scientific research program to be found anywhere in the ancient world. He had a knack for getting his hands dirty in areas of study that would have repelled his more refined and academic teacher Plato. When Aristotle was motivating his hesitant students to roll up their sleeves and actually do the animal dissections necessary for the understanding of physiology and anatomy, he told them of Heraclitus’s kitchen. A group of dignitaries came to visit Heraclitus and found him warming himself at the stove of his kitchen. They hesitated to enter because kitchens were considered undignified places, especially for serious discussions. Heraclitus said, “Come in, don’t be afraid. There are gods here too.”

14

This willingness to investigate the undignified and indecorous aspects of nature led Aristotle to study monsters directly. Being the son of a physician, he had little interest in mythical creatures or phantasms, but focused instead on teratology, the study of developmental malformations that emerge during gestation. Actually, to introduce them as “developmental” is misleading, since it was part of Aristotle’s great accomplishment to

notice

(through dissections) that embryogenesis and growth are epigenetic; that is, embryos grow from simple blobs to highly articulated forms. This seems obvious to us, raised as we are on amazing PBS-style microscopy images and documentary films of time-lapse fetal development.

Of course

the egg develops from simple to complex. But the ancients were not privy to this kind of technology-wrested information, and we should also remember that no one even knew that mammals produced eggs until the 1820s, when Karl Ernst von Baer made the discovery. A competing theory, called pre-formationism, suggested that the fully formed animal was already

complete

at the beginning of gestation, a kind of miniature seed animal; growth was simply a process of getting bigger, not progressive development. This actually seemed more reasonable than epigenesis because the ancients could not understand how molding forces could get inside the womb to sculpt the changing fetal material. By analogy, a piece of leather takes on complex form only when a cobbler works on it, and proponents of preformation

could not see any such transformative assembly in utero, so, they concluded, the zygote must be a micro person already.