On Sal Mal Lane

Also by Ru Freeman

A Disobedient Girl

On Sal Mal Lane

· A Novel ·

RU FREEMAN

Copyright © 2013 Ru Freeman

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Distribution of this electronic edition via the Internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do not participate in electronic piracy of copyrighted material; purchase only authorized electronic editions. We appreciate your support of the author’s rights.

First published in the United States of America in 2013 by Graywolf Press.

This edition published in 2013 by

House of Anansi Press Inc.

110 Spadina Avenue, Suite 801

Toronto, ON, M5V 2K4

Tel. 416-363-4343

Fax 416-363-1017

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events, is purely coincidental.

This book is made possible through a partnership with the College of Saint Bendict and honours the legacy of S. Mariella Gable, a distinguished teacher at the College. Support has been provided by the Manitou Fund as part of the Warner Reading Program.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Freeman, Ru

On Sal Mal Lane / Ru Freeman.

Electronic monograph issued in HTML format.

Also issued in print format.

ISBN: 978-1-77089-356-6

I. Title.

PS3606.R446O5 2013 813’.6 C2012-907161-7

Cover design: Kimberly Glyder Design

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund.

For my brothers, Arjuna & Malinda:

Loka, who provided the music of our childhood,

and Puncha, who kept me as safe as he could.

“Neither a person entirely broken

nor one entirely whole can speak.

In sorrow, pretend to be fearless. In happiness, tremble.”

—Jane Hirshfield, “In Praise of Coldness” from

Given Sugar, Given Salt

“‘I get down on my knees and do what must be done

and kiss Achilles’ hand, the killer of my son.’”

—Michael Longley, from “Ceasefire”

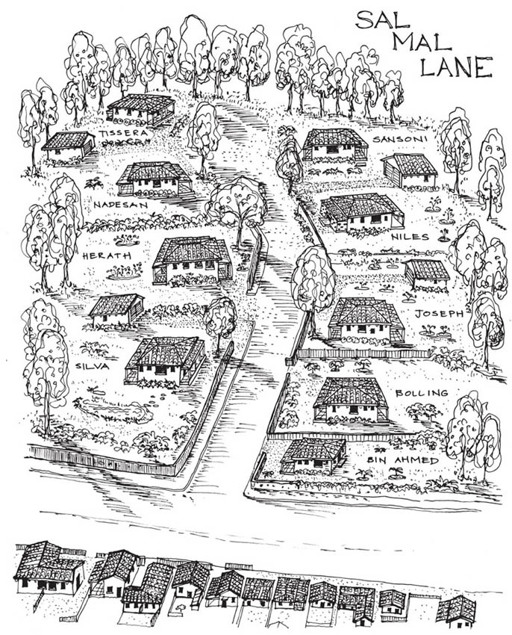

The Families of Sal Mal Lane

The Heraths

Suren

Rashmi

Nihil

Devi

Mr. & Mrs. Herath (parents)

The Bollings

Sonna

Rose

Dolly

Sophia

Francie & Jimmy Bolling (parents)

The Silvas

Mohan

Jith

Mr. & Mrs. Silva (parents)

Other families

Old Mrs. Joseph and her son, Raju

Mr. & Mrs. Niles and their daughter, Kala Niles, the piano teacher

Mr. & Mrs. Nadesan

Mr. & Mrs. Tissera and their son, Ranil

Mr. & Mrs. Bin Ahmed and their daughter

Mr. & Mrs. Sansoni and their son, Tony

Alice & Lucas

Contents

The Magic of the Stolen Guitar

A Visit to the Accident Service

Sonna Remembers Everything and Nothing

An Odd Alliance and a Little Romance

The Cricketer and the Old Man Talk of War

Out of the Blue, a Variety Show

On Sal Mal Lane

Prologue

In 1976, on the fifth day of the month of May, a month during which most of the people who lived in the country celebrated the birth, death, and attainment of nirvana of the Lord Buddha, with paper lanterns, fragrant incense, fresh flowers, and prayers mingling with temple bells late into the night, in the remote jungles of Jaffna, in the Northern Province of Sri Lanka, a man stood before a group of youth and launched a war that, he promised, would bring his people, the Tamil people, a state of their own. The year before, this man had shot another Tamil man just as that other man, the mayor of Jaffna, was about to enter a Hindu temple in Ponnalai, desecrating the temple and the minds of the faithful alike. Therefore, nobody saw fit to contradict what he had to say on that day, that fifth day of the month of May in the year 1976.

Before that day this island country had withstood a steady march of unwelcome visitors. Invaders from the land that came to be known as India were followed by the Portuguese, the Dutch, and finally, British governors, who deemed that the best way to rule this new colony was to elevate the minority over the majority, to favor the mostly Hindu Tamils over the predominantly Buddhist Sinhalese. To the untrained eye, the physical distinction between the Sinhalese and the Tamil races was so subtle that only the natives could distinguish one from the other, pointing to the drape of a sari, the cheekbones on a face, the scent of hair oil to clarify. But distinctions there were, and the natural order of things would eventually come to pass: resentment would grow, the majority would reclaim their country.

So it was that after the British had left the country behind, when what was said of them was that there was no commonwealth, there was only a common thief, the left-behind majority decided to restore pride of place to the language of the majority, which, among other things, meant that all children would be instructed in their mother tongue: the Sinhalese in Sinhala, the Tamils, Muslims, and Burghers in their language of choice but, in the end, not English, not the language of colonialism, which would now be taught only as a second language. And this policy, along with the corresponding policy of conducting all national business in Sinhala, with translations offered in the newly demoted English and the official Tamil language, created a disruption of order that would forever be known as the Language Policy. As though the Language Policy was itself a period of time and not a policy, debatable, mutable, and man-made, unlike time, which merely came and went no matter what was done in its presence.

If the policies of the British and the politics of language were the kindling, then rumor was the match that was used by men who wanted war to set them ablaze. These rumors were always the same: pregnant women split open, children snapped like dry branches, rape, looting, arson, mass graves, night raids, and other atrocities all happening “before their eyes,” that is, “before the eyes of sister, brother, father, wife.” The kinds of eyes that ought to be blinded before having to see such things. The kind of sight that once heard of necessitates an equivalent list of atrocities to be committed, in turn, before other sets of eyes. Eyes that also deserved no such sight, for who did? Which of us, taken aside, asked privately, would believe it not only possible but practical and desirable that any other of us ought to witness such acts?