Once Upon a Wish (33 page)

Authors: Rachelle Sparks

She glanced at Dakota, and the words, her voice, flowed heavily, resiliently, around the heavy lump in her throat. She made it through the cantata as she had the rest of the Christmas season, with a forced smile and a sickened heart.

“Mama, can we go home to play with my new toys?” Dakota asked the next day. It was 1:00 p.m. on Christmas afternoon, and the family had just finished eating a big, traditional meal at Papaw’s, Henry’s father’s, home.

The adults had gathered in the living room, drinking coffee and squeezing dessert into their stuffed bellies, while the kids played with their new toys. Sharon looked down at her son, who loved playing with his cousins, especially on Christmas, and smiled as best she could.

“Sure, baby,” she said, keeping her tears tucked away.

“Jingle Bells” and “Deck the Halls” swirled softly around the car on their drive home as Sharon glanced at Dakota, whose head was resting on his seat, eyes opening and closing slowly.

“Mama, thank you for a wonderful Christmas,” he said, looking at Sharon as she kept her eyes on the quiet, open road, not a soul around.

She looked at him with smiling eyes full of tears that she quickly blinked away when she turned her head back to the road.

“This was the best Christmas ever,” he added.

She couldn’t look at him again. She stared at the highway,

reached a hand over, and squeezed Dakota’s knee, pursing her lips into a half smile, just in case he was looking to her for a sign that everything would be okay.

She knew this wasn’t his best Christmas ever. In her mind, the piles of toys in their trunk should have made him feel better. The distraction of family, the excitement of the holiday, should have been enough, but it wasn’t.

It was Christmas, and he wanted to go home and rest.

“You’re welcome, baby,” was all Sharon could manage, the lump in her throat suffocating.

The sweetness in Dakota’s voice, the kindness in his eyes that afternoon, would live inside of her forever. She believed it was his way of telling her that, somewhere, deep, deep down, he knew something was terribly wrong.

They both did.

4

4

“The doctor needs to speak with you,” a nurse said the next day at Dr. Blair’s office. “Dakota, sweetie, come with me to watch some cartoons.”

Sharon didn’t know this nurse, but even the eyes of a stranger could not conceal such a dark, unwanted secret.

God, this can’t be happening

, Sharon pleaded. She wanted to stay right there, in that moment, before another word was spoken. She clung to those last few seconds of not knowing, of having an ounce left of hope. She wanted to live in that moment forever.

“Sharon,” Dr. Blair said when she walked into the room. She spoke as gently as she could, and Sharon closed her eyes. There was no easy way to say it. “Dakota’s white blood cell count is through the roof. I’m afraid he might have childhood leukemia.”

There they were: the words she knew were coming. Dr. Blair wrapped her arms around Sharon as she slipped through them.

“No, no, no, no, no …” she sobbed.

Maybe if she said it enough times, if she squeezed her eyes tight enough, shook her head back and forth hard enough, this would all go away.

“This can’t be, this can’t be …” Sharon cried.

Dakota doesn’t have cancer

, she told herself, hardly able to even think the word.

Her body, her mind, numb.

She couldn’t live without Dakota, so the only option was to beat it.

Dr. Blair immediately sent her, Henry, and Dakota to Arkansas Children’s Hospital for blood tests and draws, and that day, it was confirmed. Dr. David Becton, the hospital’s chief oncologist, gave the news to Dakota in a way a child could understand.

“You have leukemia,” he said to Dakota, who suddenly turned from a growing eleven-year-old back into Sharon’s baby boy.

She watched as her son studied the doctor’s face. She wanted so desperately to wrap him in her arms, to protect him from the world, from cancer, from the rest of what the doctor was about to say, but she knew she couldn’t. This was in God’s hands now.

“Leukemia is a type of blood cancer,” Dr. Becton continued, “and the bad guys are fighting against the good guys in your immune system. We are going to annihilate the bad guys with chemotherapy, which we will start you on tomorrow.”

He didn’t tell Dakota that he suspected Acute Myelogenous Leukemia (AML), one of the most destructive, hard-to-beat cancers rarely found in children. He wanted to keep it simple but real.

“It’s going to make you sick,” he said. “And …” Dr. Becton paused.

He looked at Dakota’s beautiful, thick red hair and added, “Your hair will come out.”

“Son …” Henry said when Dakota started to cry. As his father, he needed to stay strong, even if his insides were falling apart. Henry placed an arm around Dakota’s shoulders and spoke his language. “We are in a marathon, and we are going to cross the finish line, and then we are going to keep running and running. We’re gonna keep our eye on what’s ahead, on the finish line.”

Dakota, blinking tears down his lightly freckled cheeks, looked at his dad and nodded.

“Will I ever play sports again?” he asked, turning his reddened face to Dr. Becton.

He smiled at his little patient.

“Yes, you will.”

5

5

Dakota was admitted to the hospital that day, and two hours after he got settled into his hospital bed, a Child Life volunteer at the hospital brought Dakota a stuffed toy, Doc, one of Snow White’s Seven Dwarfs. Dakota placed the doll on his lap, making room for a sheet of paper, and began to draw.

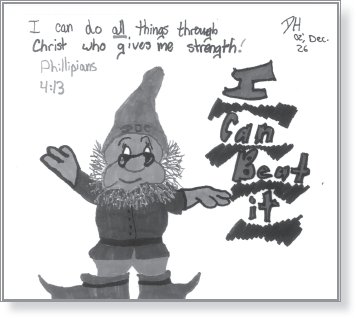

Slowly, meticulously, he sketched an outline of Doc’s body, then filled in the details of his face. Beside Doc, he wrote, “I can beat it,” and at the top of the page, added, “I can do all things through Christ, who gives me strength—Philippians 4:13.”

Sharon’s eyes welled up when she saw the picture. She immediately thought of the time Dakota had brought his small

New Testament Bible

to show-and-tell in kindergarten.

Dakota drew this picture the day he was admitted to the hospital after being diagnosed with cancer.

“How many of you go to church?” he had asked his classmates, holding the Bible high into the air. A few kids raised their hands, most didn’t, some looked around, uneasy. His teacher, Mrs. Melder, who attended the same church as Dakota and his family, stood in the corner, watching, smiling.

“Well, if you don’t, you should consider it,” Dakota finished and sat down.

Even with news of cancer and within the confining walls of a hospital instead of a football field’s freedom, his faith was still alive, and so was his will.

The next day, after Dr. Becton confirmed to Sharon and Henry that Dakota had AML, a bag of red chemotherapy, the meanest, most intense and aggressive form of treatment, hung beside Dakota, dripping its life into his veins.

“I will beat this,” Sharon read again, and she pictured him at two weeks old, lifting himself with his arms when most babies couldn’t even lift their heads.

He’s a fighter

, she thought, suddenly seeing the significance, the irony, of his name—Dakota, Native American for “Strong Warrior” in the Sioux tribe—she had always been told.

After two weeks of chemo, Dakota was in full remission. It was the end of January, but to make sure every cancer cell was gone, defeated, doctors continued his intense protocol for the next four months.