One and Wonder (47 page)

Authors: Evan Filipek

Was it too late for anything but vengeance?

But Abbie filled his arms, cuddled against him in homely blue gingham, scarcely bigger than a child but with the warmth and softness of a woman. She was more beautiful than Matt had remembered. Her arms crept around his neck.

“Will you, Mr. Wright?” she whispered. “Will you?”

A vision built itself up in his mind. The omniscient, omnipotent wife, fearsome when her powers were sheathed, terrible in anger or disappointment. No man, he thought, was ever called upon for greater sacrifice. But he was the appointed lamb.

He sighed. “God help me,” he said, “I will.”

He kissed her. Her lips were sweet and passionate.

Matthew Wright was lucky, of course, far luckier than he deserved to be, than any man deserves to be.

The bride was beautiful. But more important and much more significant—

The bride was happy.

This story is every bit as fabulous a romp as I remembered. It is also a fine study of the dangers in evoking supernatural powers. The conclusion makes perfect sense. The man is such a turd, while the girl is trying so desperately to win him, and she really would make a good wife. She is dedicated to the wifely arts, and good at them. Her pain is completely understandable, as is her outrage when she discovers how he has manipulated her. But she does love him, and forgives him the moment he agrees to marry her. I suspect she is too good for him, but that's her choice. She finishes happy, and we may be sure he will do everything in his power to keep her that way. It seems like a perfect story.

—Piers

MYRRHA

Gary Jennings

September 1962

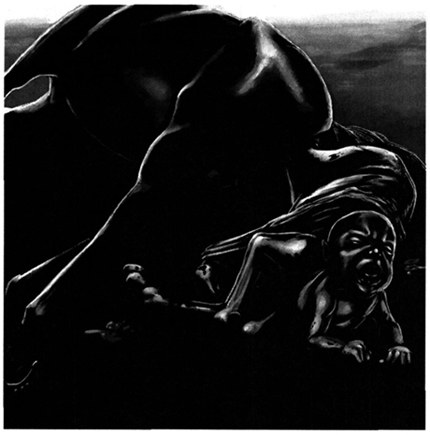

I remember this as an utterly savage story of revenge for a personal slight, phenomenally out of proportion to the offense. I remember Myrrha as a beautiful magical princess, or the equivalent. It has subtleties I'll discuss in the Afternote. I regard it as a classic of horror.

—Piers

Excerpts from the report of the court-appointed psychiatrist, concurring in the commitment of Mrs. Shirley Makepeace Spencer to the Western State Hospital at Staunton, Virginia:

To all stimuli applied, subject remains blind, deaf, mute and paralyzed . . .

Catatonic schizophrenia . . .

. . . complete withdrawal. . .

Briefly, subject's formerly uneventful domestic life was recently disrupted by two tragic circumstances. Two loved ones died violently; but by indisputable accident, as attested by attending physicians.

To judge from her diary, subject reacted rationally enough to the

fact

of these deaths. Traumatic withdrawal appears to have developed from her inability to accept them as accidental. Although an intelligent, educated woman, she mentions toward the end of her diary, “a blight, a curse.” When Mrs. Spencer hints at suspecting her innocent house guest of complicity in the tragedies, the textbook syndrome is complete.

Events leading up to her psychogenic deterioration are set down in subject's daily journal. The appended extractions have been arranged in narrative form, edited only in the excision of extraneous matter and repeated datelines.

NOTE

: The last, unfinished sentence, which subject wrote just before the onset of catatonia, is inexplicable. In the absence of any other indication that she was obsessed with classical mythology, the final entry can only be dismissed as hysteric incoherence.

Excerpts from the journal of Mrs. Shirley Spencer; dated at intervals, May 10, 1960 to final entry, sometime in July, 1961. Intervals of one day or more are indicated by asterisks:

I had forgotten how beautiful Myrrha Kyronos was. Is, I should say. When she arrived this morning, I just had to get out the old Southern Seminary annual and look up her picture. She hasn't changed an iota. She was a year ahead of me at school, probably a year older. That would make her 31 now, and she might just have doffed the cap and gown! And after that long ocean crossing, and the ride in the trucks and all, and having to mother a dozen horses and half a dozen helpers the whole way!

Tom's mouth fell open when he met her. Afterwards he said if he'd known what a “temptation” I was putting in his way he'd never have agreed to let Myrrha come for the summer. Pooh to the temptation; Myrrha's interested in nothing but her horses. And lovely creatures they are; she must

have rounded them up on Mount Olympus. By comparison, our gentle old saddle jades here on the farm appear as torpid as tortoises.

Myrrha has certainly brought excitement. Right from the start, when her letter came. I don't believe Mr. Tatum bothered to stop at any mailbox between Warrenton and here, he was so anxious to deliver that letter from Greece. And I was just about as amazed as he was. Myrrha and I hadn't been “close” at school, and I'd had no reason to give her a thought since then.

And now here she is. And here I am, dabbling in international relations or whatever you'd call it. This is the first time Greece has ever competed in the National Horse Show. When I told Myrrha we were honored to play hosts to a representative of the Greek team, she laughed and said,

“I am

the Royal Hellenic Team.”

Of course the Show doesn't come off until November. Myrrha brought the horses here now to get them used to American weather and atmosphere and feed—apparently foreign horses are a sensitive lot.

In just 24 hours, Myrrha has become undisputed queen of the Spencer acres, at least as far as our Dorrie is concerned. Dorrie, who can hardly speak “Virginian” yet, is beginning to imitate Myrrha's exotic speech. A slight accent, disarming rather than distracting, that I don't remember her having, way-back-when.

Even if we weren't just thrilled to have Myrrha herself here, we'd enjoy basking in her reflected glory. The horses are the showpiece and envy of the neighborhood, and she is the cynosure of all the local young men. Cars drive by hourly, full of sightseers either openly ogling or pretending a nonchalant interest.

For the first time today I tried to strike up a conversation with one of Myrrha's—whatever they are; she has a Greek word for them—herders, I suppose. And I can say truthfully it was all Greek to me. None of them speak English.

All are dark, saturnine, hairy little men. They keep strictly to themselves—and the horses, of course. They seem to have made provision for their keep. Whatever it is they cook for themselves down there by the barn smells like singed hair and is eaten wrapped in a grape leaf. At night they amuse themselves with a sonorous and inharmonious tweedling; Pan-pipes, is my guess.

Good old bumbling Tom got familiar enough to ask her why her husband hadn't come over. When she admitted there was none, he essayed gallantry and said he would expect her to be married to a prince. She told him quite seriously, “King Paul has only daughters.”

It does appear that Myrrha hails from one of the wealthiest families in her country, which somehow I never realized in the old days at school. Her father owns all these horses she brought, and is underwriting the expenses of the whole venture, all for the greater glory of Greece.

Myrrha told us, on arrival, that we must try to overlook any of her “so-strange” customs. I'd call them superstitions. Why, when we went walking in the woods, did she refuse to cross the branch? She said the still water would reflect her image; so what? And why, when I resurrected my old class ring, did she recoil and say she had a horror of wearing rings?

Dorrie, who has always treated our own horses with a sort of lazy, familiarity-bred contempt looks on Myrrha’s as if they were Santa's reindeer. It gives me turn, sometimes, to see her dodging in and out among their sharp hoofs, or brazenly braiding one's tail. But hair-triggered and wall-eyed as they are at any other intrusion, they suffer her as benignly as if she were their own frisky colt.

And Myrrha doesn't seem to mind, any more than she minds Tom's tomfoolery. Nowadays he pretends to be a horseflesh expert. He's forever down at the stable or the paddock, looking wise, or expounding on some trick-of-the trade known only to him, and getting in the little Greek herder's way, and one of these times he's going to get kicked in the head.

Was admiring Myrrha’ steeds today, for the umptieth time, and she scolded me gently about my own Merry Widow. Said she could have made a show-horse if I'd spent a little time and effort instead of letting her turn out to be just—“A drudge?” I laughed, “Like me?” and said that Merry and I suited each other.

Tom said maybe it wasn't too late; how about Myrrha letting one of her stallions service Merry Widow after the Show doing were over? I thought,

and told him so, that that was an indelicate suggestion. He and Myrrha laughed.

First friction tonight.

My fault. We were rehashing schooldays. Thinking it was the typical hair-letting-down hen session, I humorously confided to Myrrha that I and the other girls had considered her rather too “queenly” in her demeanor.

Myrrha was not amused; she practically demanded to know what were the necessary qualifications for queenliness. Somewhat flustered, I said, “Well, after all, the only other Greek any of us knew was the little man at the depot fruitstand over in Lexington.”

Black, an artist friend once told me, is considered a “cold” color. Myrrha's eyes are black, but they flared out like heat-lightning. I shouldn't have said what I did.

I shouldn't have said what I did. Things have been very awkward and a little awful for the past two days. Myrrha is being queenly in earnest, now, and I guess I'm in the role of the Court Fool. Tom has chided me for my “inhospitality,” and even Dorrie turns an occasional melancholy gaze on Mommy for tilting at her idol.

Myrrha unbent a little tonight; at least far enough to contribute a decanter of wine for the dinner, and invite me, too, to partake. I could have done without it. I forget what it's called—some Greek name—but its proudest feature is that it's spiced with resin (and tastes to me like old socks). Tom liked it fine; he and Myrrha had quite a high time. Quite high. Just one of their customs, she called it, but I've been gargling mouthwash all evening.

I wondered a little, at the time, when I saw her take the stone away from Laddie. It was just a plain old pebble; the dog had been idly chewing on it. She wheedled it away from him, stuck it in her pocket and walked away. Laddie didn't seem to care, and I soon forgot the incident.

Then tonight she and Tom insisted I have some more of that wretched resin wine. Tom was quite set on my not being a “party-pooper”—I think

he must have had a little something previously. So I choked down a sip, then nearly choked for real. In the bottom of the decanter was the pebble Laddie had been mouthing.

There must be some reason, but she didn't even pretend to vouchsafe one. Now I come to think, she didn't taste the wine tonight.

Bad to worse. Perhaps I really shouldn't have made such a fuss about that pebble; all the conflict seems to date from that night. Or was it from the time I made that thoughtless remark about the fruit peddler? Anyway, Tom has taken Myrrha's side whenever there's been the slightest brush between us. There've been more than a few, and not all of them slight.

The worst was at Dorrie's bedtime, when she refused to kiss me goodnight, because I'd “been bad” to her adored Myrrha. Finally, by promising to mend my ways, I bought a reluctant kiss—and tasted that damnable resin wine on my child's lips!

Don't know what to do. First that horrible scene, when I found what was left of Laddie, down by the herders’ campfires. And then the horrible scene when I confronted Myrrha—and Tom leaped to her defense.

And now both of them gone. Gone all day, and here it is after midnight. Dorrie upstairs, still awake, crying for Myrrha to come and kiss her goodnight.

Surely there can be no more horrible day in my life. Tom's confession was enough to chill my soul. And then Myrrha's denial of it—and his confusion. Is he losing his mind, or is she driving me out of mine?

He came to me, crying, pleading forgiveness “for what happened in the hayloft,” pleading that

she

had been the seducer. Then she, so cool, so self-possessed, said, “Do you think I'd give myself to

that?”

and I smelled the reek of resin on his breath.

She called our own old faithful Wheeler to witness, and he nodded witlessly and stammered yes, that Miss Kyronos had spent all night doctoring a croupy mare at the stable.

Tom, Tom, you were so bewildered. Did you confess to a dream? A wish?

Poor Myrrha. I've been so shaken by what has happened in these last couple days that haven't thought what they might have meant to her. It was my mare Merry Widow, she spent that night nursing. And here I was all ready and willing to believe—

Anyway, today we've been close friendly and forgiving, and more or less re-cemented our friendship Tom—chastened, remorseful and shamefaced—has spent all day down at the stable, taking over the care of Merry Widow. When he comes up, I'll tell him he's forgiven, too.

Tomorrow is the funeral. How many days has it been since I last wrote here? Why am I writing now? I look back over the pages and marvel at having written “there can be no more horrible day in my life.” I must force my self not to write that again here in mortal fear that I may thereby call down another blow from fate.

If only I could have said good bye, but he'll be buried in a sealed coffin. Dr. Carey says the stallion did it because, when Tom went among Myrrha's herd, he still had the smell of the sick mare on him

I don't know what I'd have done all this time without Myrrha here to help me. Bless her she realized that I wanted only seclusion. She has even neglected her duties with the horses, to keep Dorrie occupied and out of the way, and leave me to meander alone through the empty house.

But I must come back to myself. Dorrie will need me. Sooner or later she will be asking why Daddy hasn't come back “from town.”

I think I have lost all capacity for grief, all vulnerability to horror. I know I have lost all sense of time. All I have left is a mild wonder that there really can be such a thing as a blight, a curse—and wonder, why me? Why us?

I can't think when it was—it wasn't recently, because I am sure she's been gone for quite a long time. Whenever it was, she came running up the hill from the wooded place down near the branch. She was chewing happily, eating from the little paper bag she carried, and calling, “Marsh-mallows, Mommy!”

Whenever that was, she died that night in convulsions. The doctor—not

Dr. Carey; we couldn't get him; and it was an emergency—whoever the doctor was, he said she had eaten Amanita-something. Not a marshmallow, a mushroom that they call the Death Angel.