One Day the Soldiers Came (17 page)

Read One Day the Soldiers Came Online

Authors: Charles London

By living with other children in a similar situation, Mathilde did not suffer from the social isolation that Jeanine felt. She went to school and wanted to be a teacher when she grew up, like many children I met. Teachers were some of the very few positive adult figures in their lives, which might explain why so many of the orphaned children wanted to be teachers. Additionally, school was a child-friendly zone in the camps, a place where they were free to be children, usually the only one, and attending was a privilege that not everyone had. In school they could play and learn and goof off. I think some of the children saw teaching as a way to stay in school all the time. Children saw that teachers got to go to school every day, unlike most of the children. They liked the stability that implied, stability that their own lives lacked. On a more practical note, teaching was one of the few jobs one could get in a refugee camp, one of the few adult employments any of them saw.

With the other children, Mathilde laughed and played with ease. She would like to improve camp security, “so there are no problems for girls,” she said.

Nicole, who was ten years old when I met her, had been a refugee in Tanzania since she was six. She came from the Congo and lived in Lugufu camp with her grandmother. She had been brought to me by the same aid worker who introduced me to Keto, Michael, and Melanie, though Nicole did not know them before that day. She was extremely quiet, shy with the other

children and very shy with the strange foreigner who was looking at her drawing.

“I don’t know what to say to you,” she said. She liked to draw. Her favorite subject was Art. She sang a song to the translator and myself instead of talking. Her favorite song, she said, taught to her by her mother. It is one of the songs women sing when they are getting water from the well, to pass the time together. After the song, she spoke a little more freely and told us about her daily routine.

Nicole went to school in the mornings, but only if her grandmother did not need her for work until later in the day, and only if her clothes were in good enough condition for her to feel decent. If her clothes were soiled or damaged, she stayed home, she said. It is not appropriate for a girl to go out in torn clothing, and as she approaches puberty, not safe either, said my translator.

At school, she recited her lessons and obeyed the teacher. She is polite without being exceptionally astute, I was told. I have met other girls a little older than Nicole who say more, who reflect more deeply, but Nicole possessed a gentleness that I found endearing.

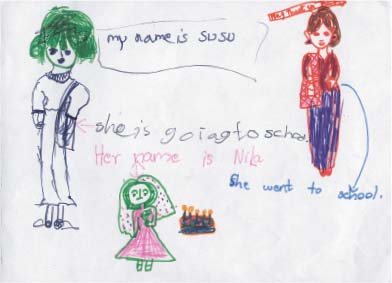

Her face flickered with a nervous smile every time I asked a question. I got the distinct impression that Nicole was not often asked what she liked or thought. Even though she had trouble thinking of what to draw and had to be prompted to depict her favorite game—Monkey-in-the-Middle—I detected in her a creative impulse that far exceeded her resources. Her desire to communicate in song spoke to this, as did the depth of her Monkey-in-the-Middle drawing. In the picture there are three girls, no more than stickish figures in the kinds of little skirts most children draw to show what is female. One of the girls faces out of the perspective of the drawing with a downturned

mouth. She is the girl in the foreground of the picture and looks quite a bit like little Nicole in crayon on paper. She had drawn a self-portrait, she confirmed (Figure 16).

What she could not express in words, she showed me with the little picture of herself in her perfect red dress. Nicole’s real dress is slightly worn out and beginning to fray at the edges.

“My favorite place to be is the well,” she said. I can picture her, the little girl in the picture, tossing a ball back and forth and splashing around in the water.

“I have lots of friends to play with at the well,” she said. “I like the well more than any other place. In school, the boys take the balls away.” Even doing drawings before our interview, the boys took half of Nicole’s paper away.

“At the well,” she explained, “I can play with my friends and have no worries. I play jump rope and monkey-in-the-middle, and this is my best time.” She smiled proudly, unlike the little girl in the drawing.

This is not to say that girls are the only ones who have a hard time in refugee camps or that they are the only ones who have to manage their own survival or that of their friends and families. Boys face many problems as well. The lack of opportunity can make them feel inadequate, unable to make the leap to manhood that employment and self-sufficiency signify. Without much to do, they are easy targets for military recruiters, criminals, pimps, or drug pushers. Seen as adult-like, with adult capabilities (look at Johnny and Luther Htoo, look at Paul, the precocious child-soldier), boys are often sent from the camps to the cities to work on their own, support themselves. They become part of that mass of boys on the streets of cities of all the world, hopefully finding fellowship with each other, staying clear of crime and unscrupulous police officers, and surviving.

To go to the city where there are opportunities or stay in

the camp where there is international aid? To go to school and prepare for the future or to work now and have something to eat, to feed the younger siblings? These are no easy choices for young people (or adults either!). The most resilient kids I have met seem to be the ones who engage with these choices, who think critically about them, who feel a sense of responsibility towards others but also towards what they often call “the right things” or “good things” or sometimes frame in religious terms with “God.”

For children who do not make it to a refugee camp where at least some measure of protection and stability is provided, these choices are all the more important.

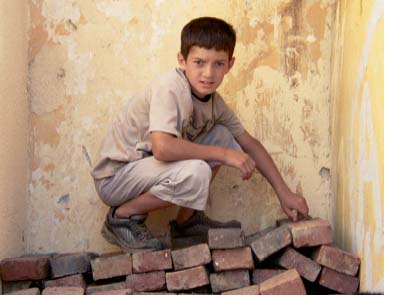

Furaha was fifteen years old when we met in Bukavu, the

war ravaged Congolese city on the lake. We met in a children’s shelter in one of the neighborhoods high above the city. Groups of children ran between the buildings carrying shovels, digging drainage ditches to keep the water from tearing apart the buildings, which were all in danger of toppling due to the heavy rains and the unstable ground.

Furaha and her four young brothers fled the fighting in their village outside Bukavu in April 2000. She is a tall girl with short hair and a severe expression. She speaks very quickly. When I ask a question she always looks down at the floor to listen, pauses, looks up at me again and rattles out her answer as if it had been waiting in her all the time.

“Furaha,” I ask, “how did you come to the city? What happened?”

“My father and mother were killed by the soldiers. We couldn’t stay because of the violence. After my parents died, we had no home, no place to stay. We came to the city on our own,

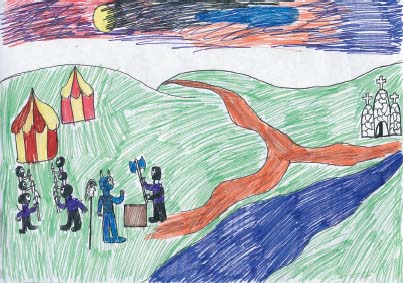

Figure 1. Miroslaw’s depiction of the Battle of Kosovo and the Death of Lazar. The 1389 battle still haunts the province of Kosovo.

Christof, a boy of mixed Croat-Serb parentage, suffered torment for his ethnicity in the years after the war in Bosnia.

All drawings and photographs courtesy of the author

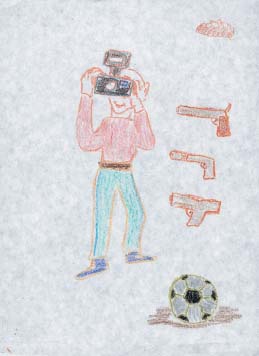

Figures 2, 3. Images of school, soccer, and violence dominate the drawings of most former child soldiers.

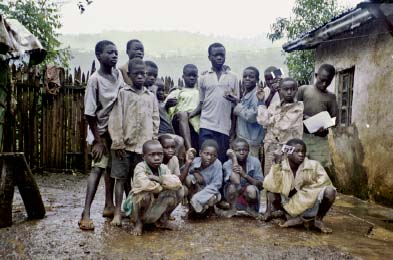

A group of former child soldiers in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, some of them, including Paul and Xavier, had been there for months, unable to find relatives or a foster family willing to take them. Reintergration into civilian life is often the hardest part of recovery.

Figure 4. Keto’s depiction of his escape from the war in the Congo.

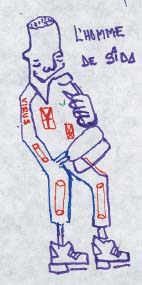

AIDS is destroying the fabric of society in much of sub-Saharan Africa. One boy’s drawing of “AIDS Man.”

Figure 5. Melanie drew images of different things she saw when she fled the Congo. The weapons remain ingrained in her mind.

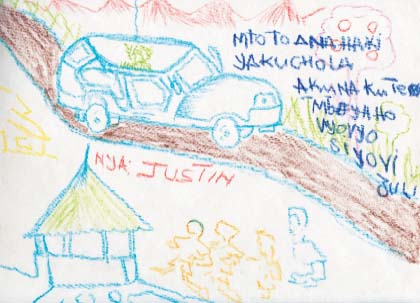

Figure 6. Justin found comfort in the rhetoric of children’s rights. Here he states that children have the right to go to school and to work.

A group of Sudanese children living in Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya, horsing around with the author in the summer of 2003.

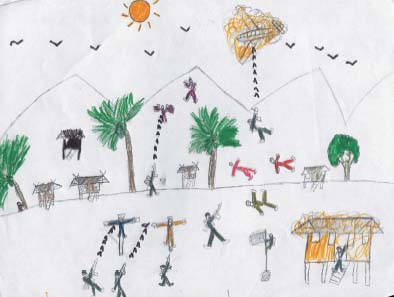

Figure 7. Nicholas drew the attacks on his village, which continue to haunt him. In the picture, he hides behind a tree, a tiny witness to the carnage.

Figure 8. May longs to attend school, believing that school, and only school, is the key that will open the door to a brighter future.