One minute to midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the brink of nuclear war (32 page)

Read One minute to midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the brink of nuclear war Online

Authors: Michael Dobbs

Despite the shadow hanging over him, Romanov had been put in charge of the central nuclear storage depot, where the warheads for the R-12 missiles were stored in shockproof bunkers. The site was hidden in a wooded hillside just north of Bejucal, a flea-infested town of muddy streets lined with dilapidated bungalows, some twenty miles from Havana. A drive-through bunker had been dug into the hillside, covered with reinforced concrete, and backfilled with earth. It had two wings in the form of an L, fifty to seventy-five feet long, connected to an underground parking garage. A circular access road permitted nuclear warhead vans to drive into the bunker from the north entrance and exit from the south entrance. The entire fenced-in complex covered about thirty acres and was easily visible from the air.

Originally constructed by the Cuban army for storing conventional munitions, the bunker had been adapted for nuclear warheads. The general staff had drawn up strict specifications for securing and maintaining the warheads. They were to be stored twenty inches apart from each other in an installation that was at least ten feet high. A space of at least one thousand square feet was required to assemble the warheads and check them out. The temperature in the storage area must not be permitted to rise above 68 degrees. Humidity had to be kept within a band of 45 to 70 percent. Maintaining the correct temperature and humidity levels was a constant struggle. The temperature inside the bunker never dropped much below 80 degrees. In order to bring it down to the maximum permitted level, Romanov had to scrounge air conditioners and boxes of ice from his Cuban hosts.

The stress of handling the equivalent of two thousand Hiroshima-type atomic bombs weighed heavily on everybody. Romanov, who was only getting three or four hours sleep a night, would have a fatal heart attack soon after returning home. His principal deputy, Major Boris Boltenko, would die a few months later of brain cancer. Fellow officers believed Boltenko contracted cancer as a result of assembling atomic warheads for a live test of an R-12 missile the previous year. By the time he arrived in Cuba, he was probably already suffering from undiagnosed radiation sickness. Many of the technicians and engineers who worked with the "gadgets"--as they called the warheads--would later develop cancer.

In contrast to the heavy security around nuclear storage sites in the Soviet Union, the Bejucal bunker was protected by a single fence and several antiaircraft guns. Romanov's headquarters were on a hill three quarters of a mile away, on the outskirts of town, in an expropriated Catholic orphanage formerly known as La Ciudad de los Ninos. U.S. planes flew overhead by day, gathering intelligence. At night, the Soviet troops guarding the site often heard the sound of gunfire in nearby hills, as Cuban militia units hunted rebels. Sometimes, nervous Soviet soldiers fired at shadows in the darkness. When they went to investigate in the morning, they occasionally found a dead pig in the undergrowth. The next night, they feasted on roast pork.

Bejucal was four to five hours' drive from the missile sites near San Cristobal in western Cuba, but fourteen hours by poor roads from the regiment commanded by Colonel Sidorov in central Cuba. Pliyev knew there would be no time to get the warheads to Sagua la Grande in the event of an American air strike. In addition to being the most distant of the three missile regiments, Sidorov's regiment was also the most advanced in its preparations. Since Sidorov had the best chance of delivering a successful nuclear strike against the United States, he would be the first to receive the warheads.

The thirteen-foot nose cones for the R-12 missiles were loaded onto specially designed nuclear storage vans, with rails that extended outwards to the ground. Night had already fallen when the boxy, humpback vans emerged from the underground facility, joining a line of trucks and jeeps. There were a total of forty-four vehicles in the convoy, but only half a dozen carried warheads. Trucks loaded with industrial equipment were interspersed with the warhead vans for purposes of disguise. Rocket troops were stationed along the 250-mile route to Sagua la Grande to block other traffic and ensure the safety of the convoy. Everybody was terrified of another accident.

Every precaution was taken to prevent detection of the convoy from the air. The operation would be carried out in darkness. Drivers were not allowed to use their headlights. The only lights permitted were side-lights--and only on every fourth vehicle. The maximum speed limit was twenty miles per hour.

Romanov and his colleagues were glad to be rid of at least some of the warheads. They lived in constant fear of an American airborne assault. They understood how vulnerable they were and found it difficult to believe that the Americans had not discovered their secret.

The CIA had been scouring Cuba for nuclear warheads ever since discovering the missiles. In fact, they were hidden in plain view all along. American intelligence analysts had been observing the underground excavations at Bejucal for over a year through U-2 imagery, and had carefully logged the construction of the bunkers, loop roads, and fences. By the fall of 1962, they had tagged a pair of Bejucal bunkers as a possible "nuclear weapon storage site." The CIA informed Kennedy on October 16 that the Bejucal site was "an unusual facility" with "automatic antiaircraft weapon protection." The agency reported "some similarities but also many points of dissimilarity" with known nuclear storage depots in the Soviet Union.

"It's the best candidate," the deputy CIA director, General Marshall Carter, told the ExComm. "We have it marked for further surveillance."

A more detailed CIA analysis three days later noted that the Bejucal bunkers had been constructed between 1960 and 1961 for the "storage of conventional munitions." Photos taken in May 1962 showed "blast resistant bunkers and a single security fence." Dozens of vehicles were observed coming and going, but little work appeared to have been carried out at the site between May and October. The lack of extra security precautions made it unlikely that the site had been "converted to the storage of nuclear weapons," the analysts concluded.

Reconnaissance planes overflew the Bejucal bunker several times during the second half of October. On each inspection, they gathered a little more evidence that should have alerted analysts to the significance of the facility. On Tuesday, October 23, a low-level U.S. Navy Crusader photographed twelve of the humpback vans used to transport nuclear warheads outside an "earth-covered drive-through structure," along with seven other trucks and two jeeps. On Thursday, the 25th, another reconnaissance mission discovered several short cranes specially designed for lifting the warheads out of the vans. The vans were all identical, with large swing doors at the back, and a prominent air vent in front, immediately behind the driver's cabin. Both the cranes and the vans were neatly parked two hundred yards from the clearly visible entrance to an underground concrete bunker. A fence of barbed wire, strung from white concrete posts, circled the site.

In hindsight, the cranes and the humpback vans were the keys to resolving the mystery of the Soviet nuclear warheads, but it would take many weeks for the American intelligence community to start connecting the dots. It was not until January 1963 that analysts examined a stack of photographs showing that the

Aleksandrovsk

had set out on its voyage to Cuba from a submarine base on the Kola Peninsula. No other civilian ships had ever been observed at the base, which had already been identified as a probable transit point and service center for nuclear warheads. The incongruity of a merchantman being sighted at such a sensitive military facility piqued the interest of the analysts, who re-reviewed all the

Aleksandrovsk

imagery. Nose cone vans were photographed on board the ship when she returned to the Kola Peninsula from Cuba in early November.

Despite making a belated connection between the

Aleksandrovsk

and the nuclear warhead vans, the analysts never made the connection with Bejucal. Dino Brugioni, one of Lundahl's top aides, wrote a book in 1990 in which he identified the port of Mariel as the principal nuclear warhead handling facility on the island. In fact, Mariel was merely a transit point for warheads arriving on board the

Indigirka

on October 4. Soviet officers, including Colonel Beloborodov, the head of the nuclear arsenal, began talking publicly about the significance of the Bejucal site only after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

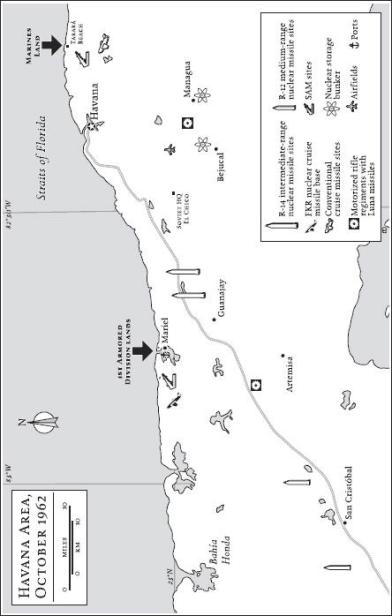

The locations of the Bejucal nuclear storage bunker and a similar bunker, dug into a hill overlooking the town of Managua five miles to the northeast, are being revealed for the first time in this book, based on a study of declassified American reconnaissance photographs. (The precise coordinates are provided in an endnote on Back Matter.) Previously unpublished photographs of the Bejucal and Managua bunkers taken on October 25 and October 26 by U.S. Navy and Air Force planes are shown on pages two and three of the third insert. The Bejucal bunker was the hiding place of the thirty-six 1-megaton warheads for the R-12 missile; Managua was the storage point for the twelve 2-kiloton Luna warheads.

The CIA's dismissal of Bejucal as a nuclear storage bunker--after it had been earmarked as the "best candidate" for such a site--can best be explained by the tyranny of conventional wisdom. "The experts kept saying that nuclear warheads would be under the tight control of the KGB," recalled Brugioni. "We were told to look out for multiple security fences, roadblocks, extra levels of protection. We did not observe any of that." The analysts noted the rickety fence around the Bejucal site, which was not even protected by a closed gate, and decided that there were no nuclear warheads inside. The photo interpretation reports referred merely to an unidentified "munitions storage site."

The photo interpreters were much more excited by the former molasses factory at Punta Gerardo, a sugar port fifty miles down the coast from Havana toward the west. The factory was located on a well-defended bay, close to a good highway network. New buildings were going up nearby. Most significantly, "a double security fence" had been built around the facility, in typical Soviet fashion, with guard posts all around. All of which were strong indicators of a possible nuclear storage site, the CIA told Kennedy just before his television address.

The molasses factory proved to have nothing to do with nuclear warheads. It was being used as a transfer and storage point for missile fuel. Once again, as in the case of the

Aleksandrovsk

and the Tatyana atomic bombs, the lack of obvious security precautions around the Bejucal site was the best security of all.

Like his Soviet opposite number, Issa Pliyev, Lieutenant General Hamilton Howze was a cavalryman by calling. His military career had spanned the transition from horses to helicopters: he now commanded American airborne troops. He already had a family connection to Cuba through his father, Robert Lee Howze, who had charged up San Juan Hill with Teddy Roosevelt. "As dashing and gallant an officer as there was in the whole gallant cavalry division" was how T.R. described him. If the United States invaded Cuba a second time, the old cavalryman's son would be the senior American commander on the ground.

Howze's men were eager to get to Cuba. The invasion plans called for 23,000 men of the 82nd and 101st Airborne divisions to capture four airports in the Havana area, including the main international airport. While the paratroopers seized the enemy's rear, the Marines and 1st Armored Division would launch a pincer movement around Havana, cutting off the capital from the missile sites. Howze notified the Pentagon on Friday that he was "having a hard time keeping the lid on the pot" of the two airborne divisions. It was difficult to keep highly motivated troops in a prolonged state of alert without sending them into action. The scale of the overall operation was comparable to the D-Day landings in Normandy in June 1944. A total of eight divisions, around 120,000 troops, would go into action across a forty-mile front from the port of Mariel to Tarara beach, east of Havana. The force that landed in Normandy on D-Day numbered around 150,000 troops along a fifty-mile front.

The invasion plan was code-named Operation Scabbards. The landings were to be preceded by an intensive air bombardment, involving three massive air strikes a day, until the missile sites, air defenses, and enemy airfields were obliterated. Low-level reconnaissance flights had identified 1,397 separate targets on the island. A total of 1,190 air strikes were planned for the first day alone from airfields in Florida, aircraft carriers in the Caribbean, and the Guantanamo Naval Base.

Inevitably, with an operation on such a scale, all kinds of problems arose. The Marines had been in such a hurry to put to sea that they sailed without proper communications equipment. Many Army units were below strength. There was a shortage of military police because some units had been dispatched to the Deep South to enforce federal court orders on desegregation. Planners had underestimated the number of vessels needed for an amphibious invasion and miscalculated the gradients at some of the beaches. There was a scramble for deep-water fording kits when the Army discovered that the beaches at Mariel were not as shallow as had been assumed. The Navy complained of a "critical shortage" of intelligence on sandbars and coral reefs at Tarara beach, which could jeopardize the "success of entire assault in western Cuba."